Hello Global Jigsaw,

As promised, this the second post this week since I’ll be taking the next one off.

It is an obituary to my cat, Tofu, who died a few days ago. Our family has shrunk and the house has an outsized cat-shaped hole in it. Read on about the life and times of Tofu - from Beijing to the world.

******

Seventeen years ago, in the summer of 2006, my spouse and I adopted two Chinese cats. We lived in Beijing at the time; a time that was liminal for both the city and for us as a couple. We had recently married after many years of dating and were contemplating having a baby. But I was ambivalent about motherhood, unsure if I were suited by temperament to its demands and constraints.

As for Beijing itself, it was a city in the midst of an enormous transition, physically and existentially. The 2008 Olympic Games were around the corner. China was rapidly integrating into the global trading system. People were experiencing unprecedented personal freedoms and transformations in family structure. And attitudes were changing in lockstep.

Pets, once considered a bourgeois anathema by the country’s ruling Community Party, had suddenly become hugely popular. Pet stores were sprouting on every street corner. The list of “new professions” published in 2004 by China’s Ministry of Labour and Social security, included “aquatic mammal domesticator” and “pet fashion designer.”

But dogs and cats still occupied an awkward middle ground between pampered and prey. During the 2003 SARS pandemic, civet cats were blamed as the source of the coronavirus, leading to vigilante gangs rounding up stray cats and dogs off the streets and bludgeoning them to death.

It was against this larger background that we decided to get a cat, before quickly deciding two would be even better, to help us practice at being parents. The pets were to be our gateway drug to babies. We knew they would require constant care and discipline. But if we could rise to the occasion, maybe we could do the same with little humans.

We christened the two kittens that joined our family on a humid summer’s day in June 2006, Caramel and Tofu. Both had been found via a notice we’d posted on the bulletin board at the local vet’s office. Caramel’s “grandmother” had called us almost immediately. She lived in a crumbling, plant-filled house in an old-fashioned Beijing neighbourhood, close to ours. Her yard was home to a number of indoor-outdoor cats that she fed. One of them had recently had a litter and she offered us a pick.

On the same day as Caramel was due to be dropped off at ours, we got a call from a cat activist- a new demographic in the Beijing of those days- about another litter that was in desperate need of adoption. We hurried to the home of a professor at a technical university in the city’s north, in whose backyard dustbin a stray cat had recently had babies. They were severely malnourished, the activist lady told us.

My spouse and I peered into the bin and saw an array of wet, black eyes look up at us in terror. We picked one at random and called her Tofu, I can’t remember why.

Tofu was bathed, dried, vaccinated and handed over to us within an hour. She was stiff with shock. For the next few days, she lay in a corner hiding, shivering with fear and hatred of us, the alien hands who had snatched her from her family. The vet told us she was close to death, so injections and medicines were part of the fearsome regime we had to subject her to in the early days.

Being Caramel and Tofu’s parents, grew us up. We gained familiarity with vaccination schedules and deworming pills. We gave them baths and brushed out their tangled hair. We read up on ideal cat diets and fed them cooked liver and egg yolk. We learned to clean pee and vomit; to love fiercely and always forgive. Our first son, Ishaan, was born 2 years later and Nico almost 5 years after, making them very much the junior siblings in our family of 6.

Together we have lived in five countries, from China to Belgium, Indonesia, Japan and Spain. We liked to joke that Tofu, who over the years grew plump and regal, had gone from Dustbin to Diplomat.

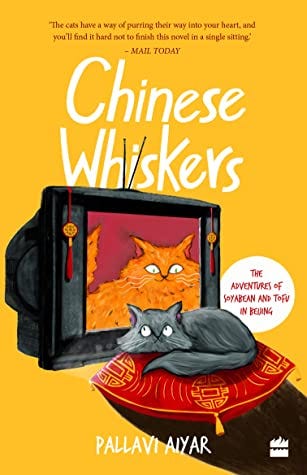

During this time, I wrote two novels, Chinese Whiskers and Jakarta Tails, that starred fictionalized versions of the cats, but were true to their catsonalities. Caramel, called Soyabean in the books, was a bon-vivant, oriented towards food and the good things in life. He demanded attention and enjoyed the spotlight.

But Tofu, whose fictionalized version retained her name, preferred to observe from the sidelines. She retained something of the feral, spurning attempts to anthropomorphize her. She would climb up the pomegranate tree in our Beijing courtyard and look up at the clouds floating across, her eyes deep wells into which I imagined a sensitivity to the unfairness of life.

Chinese Whiskers

In Jakarta Tails, Tofu’s opening chapter reads: “My family’s absence was like a body ache. I lounged by the swimming pool, stomach stretched taut, fed and pampered, thinking of my siblings and my Mama. Were they dead? Knocked down by a passing car. Were they starving? Wandering about in the cold trying to scavenge scraps until their legs gave out under them? …How did that make sense? Everyone said my yunqi, my luck, was good. But what was yunqi? A shift in the wind? A moment when your eyes happened to look more appealing than your littermates’ to the pair of Ren (human) hands deciding which one to pick?”

Tofu filled our hearts, but she was never wholly ours. She recognized our need for her and allowed us whiskery kisses and furry cuddles, but there was a private part that remained locked away through the years. And then last week, she died, just short of her seventeenth year. Her lungs gave out and the air left her.

We have been grief-struck since. But Tofu’s passing has also generated important conversations about families of choice, empathy, connection across species and the devastating, yet profound nature of love. It is the first experience with death for our boys, who have only known life with Tofu. It is also their first realization of the vulnerability that is the other side of love’s coin.

Our family now has one less globalizer- but we remember her as forever hiding amidst the trees in the garden, watching the clouds above drift with hungry wonder.

In Jakarta Tails, the final words are left, as they always were in my imagination, to Tofu:

“I stayed out in the garden. It was rare for it to be so cool. There was only a single wispy cloud drifting in the sky, changing shape as it moved.

I walked up to the frangipani tree. The fallen flowers were still heavy with water from the rain last night. I thought of how the pomegranate tree in our home in Beijing had changed into this frangipani one and how this huge bungalow had replaced our small courtyard home. We'd changed shape too, growing older, and in Soyabean’s case, at least, fatter. But I suppose it was all like the cloud. We – the cats and Ren (humans) and tree- were still the same cloud, just shifting outlines as we moved in time.”

*******

Thanks for reading. I am sure many of you have also loved and lost pets. It is terribly bittersweet that their life spans are so much briefer than ours. Much love to everyone who has known this pain. But at least we are made better by having had the privilege of loving them.

The next newsletter will be in about 10 days time. Until then.

Pallavi

PS: Do subscribe etc.

I think I will never look at a cloud with indifference again. It will contain my white labrador Choco in it.

Just finished reading The Chinese Wiskers. I was googling you and your real cats from which tofu and Soyabean were inspired. ( also I like to visualize characters ) I came upon your this post which made me little sad but in the end after reading this article made me realize that tofu lived a very happy life with her loving hoomans.

My next read will be Jakarta tails which I bought first without knowing there was a prequel, because I bought the book clearly because of the cover and really good illustrations in it.