Hola Global Jigsaw Community,

I hope everyone had a wonderful weekend.

As Indonesia gets ready to launch southeast Asia’s first high speed train, from Jakarta-Bandung, this week’s post recounts a journey I made on the same route, on the old, slow train. My trip to to Bandung was made out of a sense of nostalgia, born of the faded photos that punctuated my old history school books. For this Javanese city was the birthplace of the Non-Aligned Movement, the progenitor in some ways, of today’s Global South.

Read on, but first, do become a paid subscriber of the Global Jigsaw, by hitting the button below. Your support is deeply valued.

Bandung, Indonesia’s third largest city, has long held an allure. Surrounded by volcanic mountains, its natural fortifications and cool weather made it a magnate for the Dutch imperialists who once ruled over Indonesia. It was the military headquarters of the Dutch East Indies from 1920 on. And for much of the first half of the twentieth century, the region’s colonial planters and other well-heeled officials from Batavia, as Jakarta was then known, flocked to the city’s trendy department stores and elegant cafes for weekend revelry. A phenomenon that earned it the moniker: Parijs Van Java (Paris of Java).

In its contemporary avatar, Bandung continues to play host to battalions of day-trippers from other parts of Java, Indonesia’s largest island. These descend on the city’s factory outlet stores and designer boutiques for retail therapy. But outside of Indonesia, in countries as far flung as India and Ghana, Bandung has a different resonance.

It is black and white pictures of Asian and African world leaders, their faces lit with sepia-tinted idealism, that come to my mind when I think of the city. For it was here that the Asia-Africa conference of 1955 birthed the non-aligned movement, where recently decolonized nations attempted to carve out a principled and independent foreign policy. And it was these fuzzy, yet persistent, images from my school history textbooks that motivated me to make the three-hour journey from Jakarta.

The train ride to Bandung was a throwback to an earlier time, in itself. An old-fashioned train puffed and wound its way along a hilly track. The red, clay-tiled roofs of traditional Javanese village homes were interspersed with green-gold paddy fields. Bandung train station was a revelation. Whitewashed awnings and trimmed hedges abutting the train tracks, lent it a feel straight out of the Victorian era.

I was aware that all of this was set to change. Indonesia’s first high-speed train, built with the help of the Chinese, is soon about to transform the Jakarta-Bandung trip into a quick, slick, 40-minute trip. But it was not modernity and technology that had motivated me to travel to Bandung. Mine was a journey into history. And for that, the slow train felt apposite.

As I drove out into the historic center, the air of a cantonment town, complete with level crossings, lawn-fringed homes, and orderly round-abouts, just about holding back the chaos of a more urgent, modern city, was unmistakable.

I was staying right on Jalan Braga, the main tourist drag. Colonial buildings, patisseries, cafes and souvenir shops flanked the road. I stopped for a bite to eat at the Braga Permai, an open-fronted eatery that dates back to 1902. Originally called Maison Bogerijen, the restaurant displayed a painting of its early twentieth century façade, with linen-suited, frocked and hatted, Europeans lunching on its verandah.

Directly after lunch, I headed to the art deco masterpiece that used to be known as the Concordia, named after the Societet Concordia, an elite club of Europeans who gathered in the building for lavish dinners and balls. Today, it’s been re-labeled Gedung Merdeka (Independence Building) and houses a permanent exhibition dedicated to the April 1955 Asia-Africa conference, being the very building where the meeting took place.

It was in April 1955, that representatives from twenty-nine newly independent Asian and African nations gathered in Bandung, for a meeting that had been organized by Burma, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The delegates decided to base their future foreign policy on the principles of political self-determination, mutual respect for sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, and equality. The ideas were in direct contravention to the manner in which European colonial powers had behaved for centuries.

And thus, was born what went on to be called the non-aligned movement (NAM), wherein so-called “third world” countries refused (at least in theory) to be drawn into the Cold War and its bipolarities.

History weighed heavily in the cavernous conference room that a guide ushered me into. All the 450 original chairs and several tables from 1955 remained as silent witnesses to the past. “That’s where Nehru sat,” whispered the guide, even though there was no one but us in the room. This was not a room that brooked disrespect.

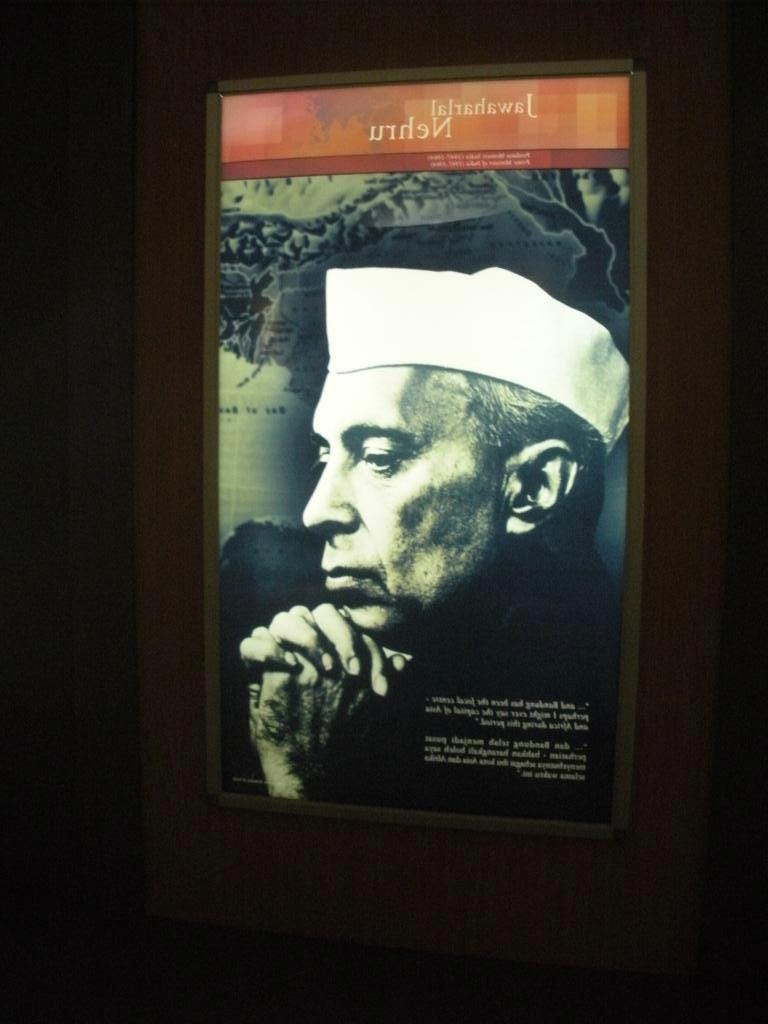

Outside the main conference venue, there were several tableaux featuring the meeting’s leading cast of characters from Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, to Indonesia’s Sukarno, China’s Zhou En Lai, and Egypt’s Nasser. The architects of NAM had also included Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. The Delhi I had grown up in had major avenues named after each of these leaders, rendering their names pregnant with nostalgia.

A number of objects, including typewriters used by the press covering the event and stamps released to coincide with the conference were neatly displayed, next to large photographs of the leaders gathering, chatting, and walking around the city.

A contemplative snapshot of Nehru dominated one wall, with a quotation, that is possibly his most famous in this part of the world, “..and Bandung has been the focal centre, I might even ay the capital of Asia and Africa during this period.” The guide points it out earnestly. “Your Prime Minister called our city the capital of Asia and Africa,” he smiled widely.

Portrait of India’s Nehru at the Asia-Africa Conference museum in Bandung. Credit: Pallavi Aiyar

Before exiting, a display of newspaper articles written about the conference from around the world caught my eye. “Chinese premier exploits his understanding of the Oriental mind- US viewed as uncouth upstart, flouting ancient cultural standards,” read one headline from the Washington Post.

Given the renewed interest in the Global South - the contemporary moniker of the erstwhile Third World - and its desire to maintain strategic autonomy -the current appellation for being non-aligned between the West and its old-new foes of Russia and China- I found myself with considerable intellectual fodder to chew upon.

But I had a last stop to make: the Bandung Mayor’s residence, a magnificent blend of colonial and traditional Javanese architecture. Inside the compound, songbirds and susurrating tree leaves provided a soothing aural backdrop. Outside however, the sizzle of noodle stalls, tinkling of pedicabs and thud of construction machinery was all enveloping. I walked out into the melee and closed my eyes, allowing the sounds to wash over me. A muezzin’s call to prayer added to the cacophony. It was a perfectly encapsulated moment of twenty-first century Indonesia.

****

Thank you, for reading the Global Jigsaw. Please share this piece with those who might enjoy it, and do leave a comment. I love to hear from you.

Sampai Jumpa,

Pallavi

Dear Pallavi,

the usual contrarian:

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.46 n.1 Cape Town Nov. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2020/v46a9

PART 2 REWORKINGS

The Decolonising Camera: Street Photography and the Bandung Myth

The visual archive of Bandung through its depictions of collaboration and conviviality between Nehru, Nasser, Sukarno, and other figures contributed to an enduring image of Third World solidarity. By the same stroke, it also generated a 'great man' version of the meeting and Third Worldism more generally with its problematic elitism and gender exclusivity.4 Though a number of delegates like Nehru and Nasser participated in later conferences of even greater size and representation, given the continuing expansion of the postcolonial world, Bandung initiated this visual symbolism of postcolonial masculine camaraderie. If the importance of Bandung ultimately rested in its establishment of a permanent idea - one elusively conjured and represented by the Bandung Spirit -the photographs of the conference facilitated this ethos of continued anticolonialism after independence. That photographs with their empiricist attributes of capturing a 'first draft of history, to use an expression of Siegfried Kracauer, would contribute to political mythology may appear paradoxical at first glance.5 Yet, as demonstrated by a number of critics touched upon in this article, modern photography, especially in colonial contexts, has frequently retained this capacity for mythmaking.

Cheers

aldo

Pleasure to read you're travelogue . The express train will make Bandung within 45 minutes reach of Jakarta i believe. India has its own Vande Bharat trains. It is good to see how fast our neighbours are growing. After all Aceh is just next door to our Andamans. You are right Bandung strikes a chord with us Indians and we are transported to the early 1950s, but the express train beckons us into the 2020s and beyond.