Becoming a citizen of the Tower of Babel

Syntax and structure vs ordering a perfect cup of cappuccino

Namaste Global Jigsaw Friends,

This week’s guest post is by academic, dancer, and amateur linguist, Ananya Jahanara Kabir whose work on creolisations and what happens where cultures, languages, and thought intersect is very much a Global Jigsaw-friendly body of work.

Her piece reminds me a little of the one I actually kicked off this newsletter with. If you haven’t read it yet, do:

Hope you enjoy today’s post, and if you do, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to the newsletter. It takes time and effort to write and produce and build a community…and labour needs compensation to be sustainable. So out with your wallets!

How to enjoy the Tower of Babel

By

Ananya Jahanara Kabir

Five years ago, I was spending a few months in Geneva during my husband’s sabbatical period at CERN, the international mecca for fundamental research in quantum physics. While embedded within one of the most resolutely provincial countries, the city of Geneva is in itself very international and multilingual, thanks to all the international organisations that dot its pristine lakeside.

It’s perfectly possible to get by in English, or skills in French that involve nothing more than reading a menu in a restaurant. But living somewhere for any length of time, even the most cosmopolitan of places, does throw up new, and unanticipated linguistic challenges that necessitate rapid thinking on one’s feet.

One such situation arose when I went to get my hair cut by an Italian chap who had been doing a fantastic job with my spouse’s hair. On arrival at the salon, I realised that I had not prepared myself at all to speak about hair, its cutting and its styling, in French. I began in English, but on noting the look of utter panic that crossed his face, I had no option but to hastily switch to French.

In about ten minutes I was fast tracking into all the necessary vocabulary and requests including 'keeping the length', 'some layering but not too much', 'cutting with extreme precision' and 'I don't like to use a hair straightener.' Since I was pinned to a hairdresser’s chair, I didn’t have the option of whipping out google translate on my ever-obliging iPhone. The main problem quickly emerged as one of mutual intelligibility. Gaetano spoke an extremely Italian French, complete with expressive body language. He was also very sincere about understanding his client's needs, just as I am super picky with instructions.

In our attempt to reach out to each other, his gestures got increasingly excitable, while my voice started rising in a very Indian effort to make myself understood. Suddenly I realised that the entire salon, full of elegant Genevoise ladies, was transfixed by this pantomime of an Indian and an Italian trying to communicate about hair in French.

In the event, we achieved good results, as confirmed by the spouse. He had already benefited from Gaetano’s skills in the past, but when those two spoke, they did so in Italian. Hence my lack of forewarning about a possible linguistic gap coming in the way of the desired perfection of my haircut.

But then, my other half and I have totally different approaches to language use out of one’s comfort zone. This became apparent very early on in our post-PhD lives. I, the person who loved to dissect dead languages for research, was staying on in the cosy bubble of Trinity College, Cambridge.

He, who preferred to communicate in equations that ran to several pages and squiggly Feynman diagrams, was off to Italy immediately after submitting his PhD to start a postdoctoral position in Milan. All gentle (and not-so-gentle) suggestions that he should take language lessons before he left were brushed aside on the grounds of ‘I have no time.’

Oh, that particular schadenfreude of, “I told you so,” when you realise from afar that the spouse has landed in a monolingual European desert where brown-skinned theoretical physicists are not a common sight. Nevertheless, a rescue mission could hardly be conducted in Latin, the language I was relying on, as I parachuted into Milan to help him out in basic matters such as taking possession of a flat.

It mattered not a jot that I had traveled for a month through Spain a few years ago, armed with little but a Latin dictionary, a set of Spanish verb tables, and the trusty Baedeker to look up train connections (we are talking about the mid 1990s here). I had vowed then, to not speak a word of any language other than Spanish to the locals, and had actually managed (including a baptism by fire at a pharmacist’s in Barcelona, where, covered in hives mysteriously gained overnight on a train journey from Paris, I uttered my first complete Spanish sentence: “tengo una alergia” – ‘I’ve got an allergy’. I hasten to reassure the readers of this august column that my Spanish has improved considerably since).

Standing outside the door of our new abode in Milan, however, one needed to be a tad more efficient than working out how to transform ‘clavis’ into the Italian for ‘key’. While I went over philological rules in my head, the other half (decidedly, at this moment, the better half) managed to catch the attention of our concierge and even procure said ‘clavis’. I could only marvel that she was called ‘Clotilde’, a classic Merovingian name—niche knowledge to be sure, and hardly helpful for practical communication with Clotilde.

Over the course of the next few years, one of us picked up fluent Italian (without going to a single language class). The other one diligently signed up for eight years of Spanish lessons at the Instituto Cervantes, used one to one lessons to improve on basic French gleaned through a year of Alliance Française fun in 1990s Calcutta, and moved in and out of German, also learnt first in Calcutta at the Goethe-Institute during a hot summer in the 1980s.

While one of us keeps stunning native speakers of Italian with idiomatic constructions and perfect accent, the other keeps wandering down philological bylanes, learning Portuguese through Spanish, and Dutch through German. Language entrances me through structure and patterns of similarity and divergence. For the spouse, it’s mostly a matter of ordering a perfect cappuccino.

Over the past three decades I’ve traveled through, and lived for extended periods in, continental Europe. I have loved the ease of slipping in and out of many languages and getting increasingly used to speaking it spontaneously rather than just being content to puzzle out the written word.

I consider my biggest linguistic achievement not examining PhD theses written in French and Spanish, but opening a bank account in Germany, in German. This summer, in Leiden, I was delighted to practice my fledgling Dutch to ask for, ‘a bread roll with new herring.’ Not really a huge challenge when you realise that the Dutch for ‘new herring’ sounds almost exactly like English ‘new herring’. And Dutch broodje (bread roll) sounds pretty much like German brötchen (bread roll). Sound, not spelling, is often the key to communication, and communication, not perfection, is what’s required.

In getting my little treat from the fishmongers, I was helped less by the knowledge that Dutch sits on that grey zone between German and English, and more by my willingness to improvise. In that sense, the dance floor has been my greatest language school.

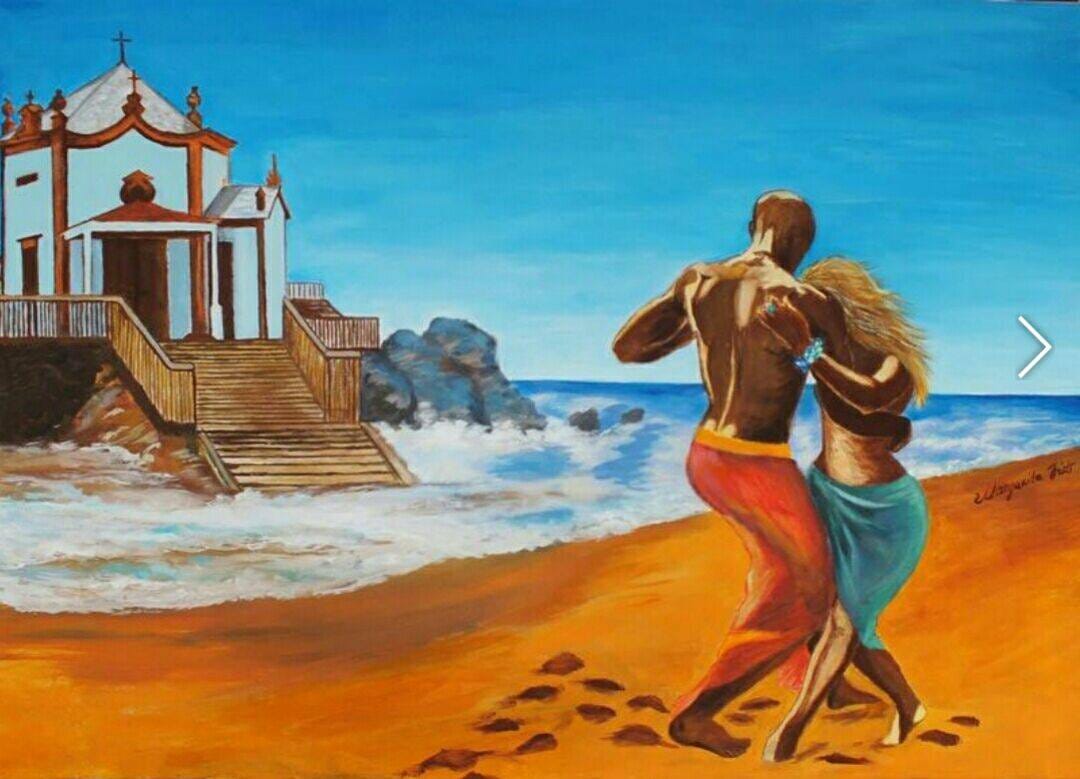

I started dancing salsa and kizomba, first for fun, and then for research on how people connect through social dances where you need to partner with another person. My research led me to dance clubs in Latin America, Europe, and Africa. Partner dancing socially is an improvised art reliant on communication and reciprocity. Those skills fed back into my conversation attempts in Spanish, French, and Portuguese, depending on where I was dancing.

The wheel has come full circle, and we are back in Geneva for a sabbatical year. This time round, I find myself very comfortable in French. Years of dancing and conducting research on dance, in Francophone West Africa seem to have pushed me to another level altogether. I was able to ply the handyman, who’d merely swung by to deposit a new laundry basket, with the information that a desk I’d failed to assemble needed his urgent attention. Merci infiniment!

Every day continues to throw up such pleasurable little challenges of being normal in a language that is not even the first, second, or third, but in that elastic category of ‘all those other languages learnt in adulthood’. In the meanwhile, I notice that the spouse too is adding to his quotidian French, almost imperceptibly—and that, this time round, he got his hair cut by a French- rather than an Italian speaker. Somewhere, somehow, our very different approaches to surviving (with) multilingualism have begun to find common ground.

*******

Ananya Jahanara Kabir is Professor of English Literature at King’s College London and the winner of India’s Infosys Prize for the Humanities (2018). She is currently writing a book called ‘Alegropolitics: Connecting on the AfroModern Dance Floor’.

*****

Hasta la proxima semana mis amigos. Take care in the while and don’t forget to spread the word about The Global Jigsaw. xoxo