“Do you speak Indian with your children at home?” It’s a question I’ve encountered with rhythmic predictability in my decades living abroad. There was a time when the “Indian” part of the query occupied my response: there is no such language… Hindi, Tamil, English is an Indian language too… yaddy yada.

But increasingly, it’s not the ignorance of my interlocutor in assuming ‘Indian’ to be a language that bothers me, as much as the fact that I speak English with my children, grew up speaking English with my parents, speak English to my cats, and dream in English. This was something that seemed quite unremarkable growing up, but increasingly it feels, if not ‘wrong,’ at least something that deserves interrogation.

Given the deep bonds between language and identity, what does it mean for an Indian who has lost her “native” languages (in my case, Hindi on the maternal side and Tamil on the paternal)? Put another way, is it possible to be authentically Indian in English?

I went to an “English medium” school in Delhi where everything, except Hindi, was taught in English. I understand Hindi well enough, although it is an oral, rather than literary language for me. I can read in Hindi, but only haltingly, at primary school level. I suppose that’s because I don’t read in Hindi. Period.

And while I spoke Hindi daily while growing up, it was exclusively to the “servants” or other non-English speaking Indians: shopkeepers, autorickshaw drivers, the security guards at the school gates, random people on the street I might need to ask for directions. The non-English speaking Indian – an overwhelming majority in the country - was but a cast of supporting characters in my life.

The numbers

India with its polyphonic linguistic make-up allowed for this state-of-affairs. We have 22 official languages and almost as many mother tongues as we do Gods. According to the 2011 census there are 19,500 distinct mother tongues spoken in the country.

But although all languages, or at least the 22 major ones, are equal, some are patently more equal than others. I’d go as far as saying that there is only one linguistic fault line that really matters. That between English and non-English, rivalled only by the division between speakers of English as a first language and the rest.

Only 0.02 percent of Indians speak English as their first language according to the 2011 census, although 6.8 percent say it is their second. Forty-three other languages are spoken more commonly as first languages than English, in Indian homes. Just about 10 percent of Indians can speak some English, including those who speak it as a second or third language.

In contrast, Hindi is spoken by 528 million people, or almost 44 percent of all Indians, as a first language.

And yet English is the language of the supreme court, of much of government and the media at the national levels, of elite business, and of success.

Indians have many ways to divide themselves- by religion, by diet, by skin colour, by gender. But the English – non-English divide arguably creates the most rarefied distinction of all.

In India, English is not just a language, it is a caste.

**********

Growing up “English” in India

I didn’t grow up feeling alienated from, or alien in, India. My roots ran deep. I was proud of my country, its diverse cultural heritage, foods, polyphony. I had no doubts about my authenticity as an Indian, because I believed the wonderful thing about my country was its resistance to the policing of its definition. There was no authority that could decide who was truly Indian or not. My idea of India was as valid as yours.

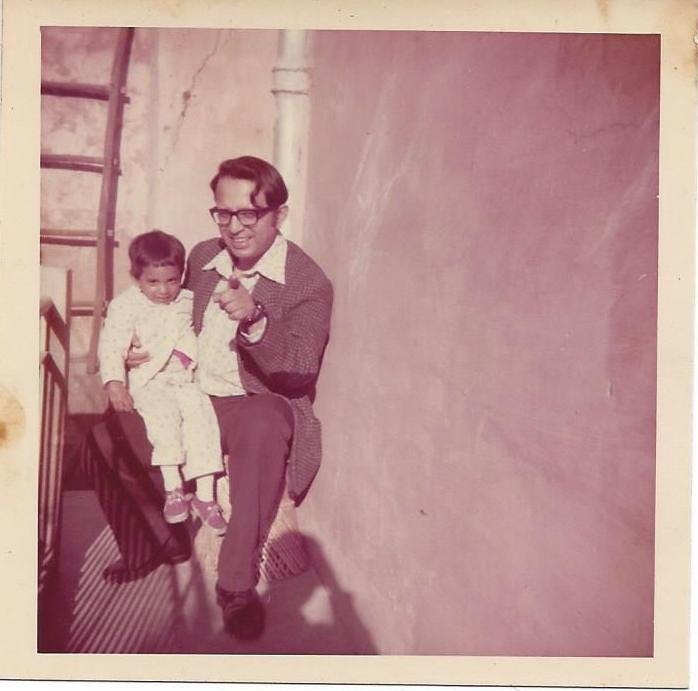

With my dad in New Delhi, probably circa 1977

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, had famously described India (in superb English) as an “ancient palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously.”

I was ergo, one type of Indian, as valid in my Indian-ness as any other type.

Moreover, although I was an English-speaking Indian, my generation had decolonized the language, domesticated it. I inhabited Englishness with less bathos and pathos than the generation who’d actually been taught at school by Englishmen. My accent was free of stuffiness, my consonants unapologetically Indian-hard, and my vowels free of striving for some sliced-cucumber-sandwich ideal. My English was unselfconsciously peppered with “acchas” and “chalos” and “yaars.” It was breathable and loose like a saree, not buttoned up in a suit and tie.

And furthermore, English was India’s lingua franca. It allowed for Hindi-influenced northerners and the Dravidian language speakers of the south to be compatriots who could communicate. It was the linguistic bridge upon which the country relied for internal connection.

With my brother in London, around 1982. The first time I ever visited the U.K. The next time was about 2 decades later.

*************

But…

Yet. The older I get and the more time I spend abroad, the less convincing some of these arguments sound. It is true that India is a palimpsest and has absorbed cultural influences from elsewhere to make them her own. But unlike the Mughals and their descendants who stayed and became Indian, so that Urdu – Persian and Arabic infused Hindi – is as “authentically” Indian as turmeric, the British (and their language) were always a race apart, who when the time came, left almost overnight.

Of India’s population of 1.3 billion people, only between 125,000-150,000 are Anglo-Indian or Indians with some English ancestry. In contrast, there are over 200 million Indian Muslims.

And while English-Indians like those in the milieu I had grown up in, had certainly made the language their own, their playful bending of the idiom popularized in literary works by international stars like Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy was of a very different order to the Indian-English of the English-aspiring, the vast majority of India’s so-called English speakers.

Most Indians didn’t joyfully play with the language as much as desperately try, and usually fail, to gain a modicum of fluency in it. The language they learned was syntactically wrong, badly pronounced and had the air of desperation about it. It was the ticket to a better life, but one that usually remained out of reach no matter the effort.

So that while it is true that as a lingua-franca English connects India, it also disconnects it. The English-Indian caste is implicated in a system of inequality that is corrupting of the country’s constitutional ideals of democracy, justice, liberty, equality, fraternity, human dignity and the unity of the Nation.

*********

The left-behind offspring?

Given language’s impact on the way in which we understand the world, the fact that mine, English, is inescapably mediated through the colonial gaze, is an uncomfortable one that I am trying to work through. It’s not as straightforward as claiming, like I used to, that English is an Indian language and my Indianess is as valid, as authentic, as anyone else’s. The role of English in perpetuating a system of oppression and racism is an uncomfortable reality.

In India, I don’t just speak in English – I am of the English caste. It’s taken the constant querying about language from foreigners to make me confront how I might come across to the non-English speaking Indian as “other,” colonial in privilege, deracinated. There is a derogatory Hindi phrase that goes: Angrez chale gaye, par apni aulad chhod gaye (the English may have gone, but they’ve left their offspring behind). Am I the offspring?

*********

Over the last couple of decades, a shift in Indian’s linguistic hierarchy has been underway. The importance of an English-Indian like me is on the wane politically, while Hindi-based mass culture as encapsulated in music and movies is indisputably dominant.

For India, this feels like a positive development. For me, it’s an existential one. If English becomes less important in India- what of me? In what ways does the development diminish my claim over my country?

This entire meditation was provoked by a conversation I recently had with Nico, my ten-year-old. Nico was born in Brussels, grew up in Indonesia and Japan and is now studying at a British school in Spain.

“What does it mean, Muma,” he asked me, “when people say, ‘Where are you from?’ What is “from?”

I wracked my brains. “It means what countries your parents are from,” I replied. “But what does that mean?” he countered.

I sighed. “I suppose it’s a question that’s trying to ask about your identity. What you feel like?”

“Oh,” he said. “Then, I’m from England. Or maybe, America. Because my identity is English.”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at that response. So, I wrote this post instead.

*******

Thanks for reading and please do share this newsletter on your social media. If possible, I’d be grateful if you’d subscribe. I post content here that is free to read, but takes time and effort to craft, write and publish.

Finally, I’d love your thoughts, so do comment.

Until next week, take care,

xo

Pallavi

When you look at the world I think more and more people are like Nico. Multicultural and multiethnic. Good write up.

Very well written. Your essay helped me organize my own confused thoughts about all this. 🙏