Dear Global Jigsaw,

Seasons around the world vary. In Spain we are enjoying fall, in Indonesia it is rainy season. But in Delhi, my hometown, it’s the time of year everyone has come to dread: pollution season. A thick toxic smog cloaks the city, during this now annual period, which begins in late October and carries on until Spring.

As has become the annual norm, the Delhi government has declared the bad air a “medical emergency” and the the Supreme Court has ordered special measure from a stop on all construction work to limiting the number of vehicles on the roads. Schools are closed indefinitely to protect students. There is a run on air purifiers and other pollution mitigation equipment for those who can afford it.

Its almost like a reprisal of the COVID pandemic for this city and its surrounding areas, a region that is home to some 55 million people: work-from-home mandates, children cooped up at home, and masked faces on the streets .

On Monday, Delhi had the world’s worst air pollution, according to IQAir, a Swiss company that measures air quality. The reading on its index rose to over 1,600. Anything over 301 is considered “hazardous” to the health. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers anything beyond 500 to be “off the charts.”

According to a 2023 air quality life index, compiled by the University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute, the people of Delhi could have their lives shortened by 11.9 years due to the poor air they breathe.

xxxxx

Sadly toxic air and I have a long and intimate relationship. For long before Delhi had the dubious honour of world’s most polluted city, the title belonged to Beijing where I lived between 2002-2008.

For today’s post I bring you the story of air pollution in Beijing and Delhi. I would normally say, enjoy - but not today.

Oh, please do renew your subscriptions and if you haven’t already, do consider subscribing. Thanks!

Having grown up in perennially polluted Delhi, smoggy skies were so unremarkable to me that I didn’t even notice anything was awry in Beijing for years after moving there in 2002. Till one spring morning in 2006.

It was an ordinary start to the day in most respects. I ate a quick breakfast of jian bing, crispy dough and egg pancakes brushed with a spicy sauce, and then made my way to my laptop. It was only when I looked out of the window above my desk that I realized this was anything but an ordinary morning. I blinked hard, gasping in wonder at the apparition: a cerulean blue sky, punctuated by the sweep of rolling hills. For the 10 months I had lived in this apartment, the view from my study had only revealed the low, tiled rooftops of the courtyard homes that clustered around our complex and beyond that a patch of turbid sky that varied only in the shades of grey it displayed. The appearance of the hills felt magical, except it was not magic, merely the absence of air pollution.

Before that moment, I don’t think I had really “seen” the dirty air in China. My first few years in Beijing only evoke romanticized nostalgia. I remember the summers as hot and languid. The fall was short and crisp, the streets layered with fallen leaves the colours of sunset. Winter conjures images of candied crab-apple vendors and fearsome winds that originated in Siberia.

Rich-country expats certainly muttered aplenty about Beijing’s toxic air but my reaction to these were initially akin to that of most Chinese themselves: dismissal as overblown first-world concerns. In China, as in India, the general attitude even to days when the skies were turgid enough to cut with a knife, was to associate the griminess with weather phenomena like fog and sandstorms, rather than pollution.

Beijing’s poor air was the result of compound factors ranging from vehicular to industrial sources. But it was exacerbated by unhelpful geography, a feature that Beijing shares with Delhi. The Chinese capital has mountain ranges to its north and west, which prevent the pollution drawn in from the industrial townships to its east and south from escaping. Also, low temperatures in the winter create an inversion layer, a phenomenon mirrored in Delhi, so that cold air bands get pressed under a warmer air mass, trapping pollutants close to the ground.

As I began to engage with China’s degraded environment as a reporter, the parallel fact of Delhi’s smoggy skies become harder for me to ignore. Every Christmas holiday I returned home to putrid air that left my eyes smarting and throat aching as much as anything I had experienced in China. Yet, whenever I raised the issue with friends, I was met with blank stares or eye-rolling intended to indicate how much of a ‘foreigner’ I had become.

Channeling one’s inner ostrich when it comes to air pollution is a universal affliction for the citizenry of developing Asian countries. It is not the outcome of China’s authoritarian politics. Nor is it the result of India’s chaotic democracy. To understand what from a rich-country perspective is the developing world’s peculiar obduracy in reacting to air pollution one must take into consideration the fact that many Beijingers/Delhiites will die prematurely and/or suffer long years of bad health regardless of air pollution. They must grapple with a long list of possible ills including typhoid, dengue fever, tuberculosis and malnutrition, before becoming overly concerned with the cardiovascular implications of exposure to dirty air.

Yet, greater awareness can, when the information is dire enough and perceived as such, eventually lead to change, a process that by the time of the 2008 Olympics had clearly begun in China. According to United Nations Environment Programme, US$17 billion was spent by the Chinese government on environmental projects between 2001 and 2008.

By the time of the Olympics, 90 per cent of Beijing’s wastewater was treated (compared to only about 40 per cent in Delhi at present). New roads, railway and metro lines had been built to encourage an alternative to cars. The number of public buses doubled to 20,000 between 1991 and 2007. Over 200 polluting industries (including cement, lime, brick and coke plants) were relocated outside the city and more than 16,000 small coal-fired boilers were converted to natural gas.

On a personal level, my relationship with pollution became more adversarial after my son was born, a month after the Games. First-time parenthood engendered a siege mentality in me. I began to navigate the quotidian as though under attack, spotting enemy forces in the food we ate, in the water, in the milk and in the air. As my boy approached his six-month birthday, he began wheezing like a grandma on a mountaineering expedition. He was diagnosed with a lower respiratory disorder, bronchiolitis, that our pediatrician said was common in babies born in Beijing. Our nights became nightmarish as we stayed up watching over our child gasping even in his sleep.

A few months later we moved to Brussels, the Belgian capital, where my husband began a new job. Our son, now 16 years old, has never experienced any respiratory symptoms since. The ability to up and move is a deep privilege. That often-annoying demographic, the expatriate, have choices that most locals do not. They have resources, in terms of both information and money, that most locals do not. Most importantly, they have an exit.

I well appreciated why expat moaning about pollution could feel so egregious to those for whom toxic air was not just a hardship posting, but life. This divide between the ‘tourists’ and those serving a life sentence in the acrid megalopolises of the developing world is the unfair result of the throw of some cosmic dice. As is the faultline between those Indians wealthy enough to afford air purifiers and N95 masks, and the majority who cannot.

xxxx

In 2014, I visited Beijing and Tianjin, for a World Economic Forum summit. While the westerners in our group had come prepared with facemasks and a working knowledge of PM2.5 levels, the Indians kept squinting into the smog looking perplexed. I was repeatedly approached by the Indian participants about whether ‘this’ – the air outside our conference centre – was what all the fuss was about. ‘But, this is nothing,’ they told me in bewilderment. I giggled.

It reminded me of my own reactions as a novice reporter in China. On field trips with western colleagues into the country’s interior, everyone would be reporting on the dire poverty, when all I could think on beholding the decently clothed, electric fan-owning ‘poor’ was, ‘This? But, this is nothing.’

Until a few years ago, the China-oriented “airenfreude”, so common in western media, was prevalent in India as well. It was a comfort to think that the Chinese had some real problems too. But today the one race that India is winning against China, is the one to the bottom on bad air.

xxxx

How did China emerge as the frontrunner among polluted Asian countries in tackling dirty air?

It instituted a broad, regionally coordinated system of air pollution monitoring, installed high-tech pollution abatement equipment on a majority of its power plants as well as devised means to restrict car ownership in major cities. China has a network of 2,100 air quality-monitoring stations in over 1000 cities . Its coal use is down and coal-fired power plants are increasingly efficient. In the first half of 2024, China reduced coal power permits by 83% compared to 2023. To replace coal, China has been rolling out the world’s biggest investment in wind and solar power.

A University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute has shown that China reduced air pollution nearly as much in seven years – between 2013 and 2020- as the United States did in three decades. The reduction in harmful particulates in the air during this time was 40%.

Beijing achieved this by instituted a broad, regionally coordinated system of air pollution monitoring, installed high-tech pollution abatement equipment on a majority of its power plants, as well as devising means to restrict car ownership in major cities.

It’s important to note that despite the widespread belief in India that the Chinese government has carte blanche to push through any reforms it likes, in fact the ruling party is not a monolith. Making environmental protection a priority is an ongoing and conflicted process. Over the years, it met with considerable push-back from vested interests both within and outside of the ruling party. And yet Beijing persisted, partly as a response to civil society pressure from below and partly from an elite-driven realization of the economic consequences of unchecked environmental damage.

In 2014, China updated its environmental protection law to give local authorities the power to detain company bosses who didn’t complete environmental impact assessments. The law also removed limits on the fines that firms could be subject to for breaching pollution quotas.

China’s pollution fighting attempts were multi-pronged, but with a focus on heavy industry. Despite being the mainstay of China’s energy mix, coal-fired power plants came under the hammer. In March 2017, the national government announced the closure, or cancellation, of 103 of these plants, which would have been capable of generating more than 50 gigawatts of power in total. Further, all new coal-fired power plants were mandated to be “ultra-low emissions”, or about as clean as natural gas plants.

Vehicular pollution was not ignored. Measures to restrict car ownership were put in place in many cities. Beijingers, for example, can only buy a new car if they do not already have a vehicle registered under their name. They are then eligible to enter a monthly lottery for license plates.

Finally, China learnt that for anti-pollution measures to be successful they had to consider entire air sheds, or zones within which air circulates. Although a few Indian cities (notably Delhi) have taken some anti-pollution actions, these are not coordinated at the regional level. But Beijing’s experience with polluted neighbouring areas like Tianjin and Hebei has proved that unless the North Indian states of Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan work in tandem with Delhi, even Herculean efforts by the capital city on its own will not prevent it from choking.

For India, China should remain the model to learn from when it comes to the air. Beijing’s experience shows that blue skies entail a tough, long slog that requires, among other elements, political will, civil society activism, commercial compliance, and bureaucratic incentives. There are no silver bullets. But air pollution is a man-made problem, with man-made solutions. It’s tough to fix, but far from impossible.

xxxx

Here are some links to pieces I’ve written over the years on Delhi’s air pollution:

https://www.firstpost.com/tech/news-analysis/india-choking-air-pollution-is-a-problem-that-not-only-needs-acknowledgement-but-action-too-3698547.html

https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/know/gasping-for-clean-air/article9329304.ece

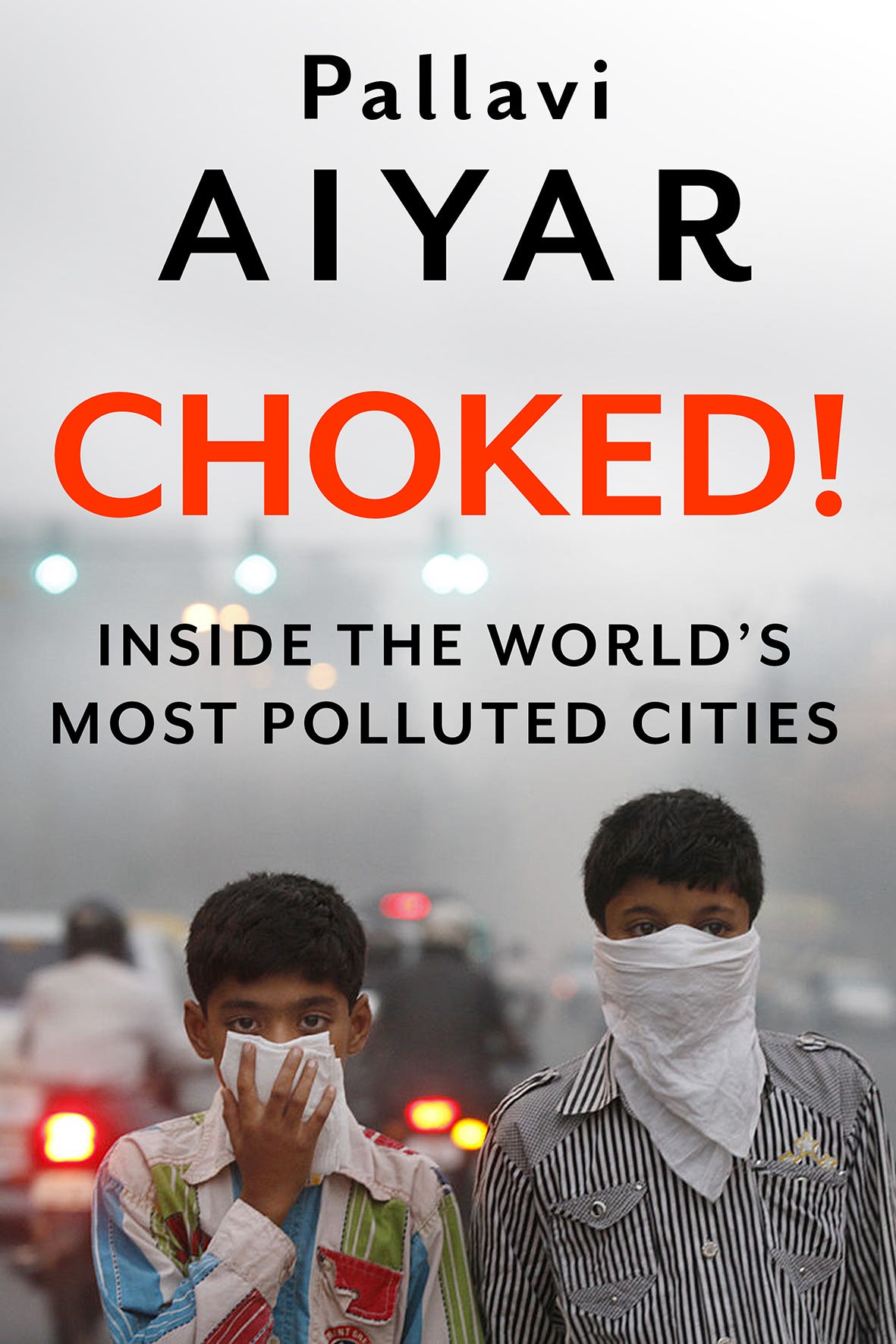

https://asianreviewofbooks.com/content/choked-by-pallavi-aiyar/

Some video links:

One more:

Thanks for reading. Do share if possible and I would love to hear any comments you might have. And please subscribe.

Hasta pronto,

Pallavi

This is going to be an unpopular opinion but here goes: I don’t think Delhi-ites care. They have always been consumers first and citizens next. The civic space doesn’t exist - ironic, given the socio-political history of Delhi. Unless they care enough about their own city, no one else can help. It’s true for all cities, but particularly for Delhi. One sees a lot more citizen action in Mumbai and Blr.

"To understand what from a rich-country perspective is the developing world’s peculiar obduracy in reacting to air pollution one must take into consideration the fact that many Beijingers/Delhiites will die prematurely and/or suffer long years of bad health regardless of air pollution. They must grapple with a long list of possible ills including typhoid, dengue fever, tuberculosis and malnutrition, before becoming overly concerned with the cardiovascular implications of exposure to dirty air."

This is so, so true! Lahore is also reeling from the same effects as Delhi. Despite informed citizenry raising the issue repeatedly, most of the ordinary population was least concerned because they have more serious issues to tackle. This is the gist of the dilemma.