Converting to the Camel

Several pieces of the Global Jigsaw - South Asia, Australia, and the Canary Islands of Spain - unexpectedly fit together at a camel-shaped point in history.

Dear Global Jigsawers,

On our recent trip to Rajasthan, my family converted to the camel. As we traveled west, deep into India’s Thar desert, our car increasingly had to share the road with this awkwardly shaped ungulate, all humps and joints and teeth.

In Bikaner, we visited the National Camel Research Centre. The boys tried flavoured camel milk and we learned that camel bone made a good replacement for ivory. In Jaisalmer, we rode camels over the sand dunes under a setting sun. Later, Ishaan bought a hand painted T-shirt of what can only be described as a camel high on hashish. (Currently, he insists on wearing the garment to bed every night.)

The Camel National Research Center in Bikaner. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

My boys riding off into the sunset on camels. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

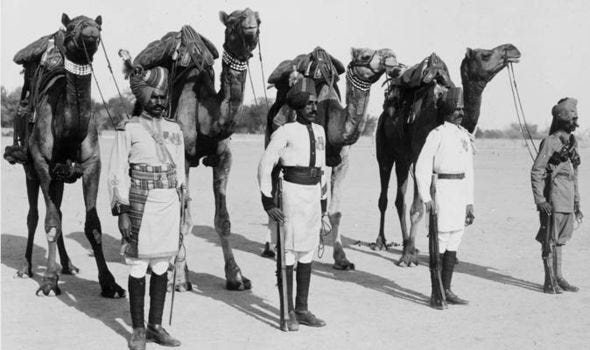

Rajasthan is synonymous with the camel. It is a region of camel polo and camel fairs. The Bikaner area even boasts a camel cavalry, one with a storied history. Under the British Raj, the Bikaner Camel Corps had helped put down the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. And in 1915, during World War 1, the corps routed enemy Turkish forces at the Suez Canal in a dramatic camel cavalry charge.

The Bikaner Camel Corps during the First World War

Today, the Indian military’s camels are mostly ceremonial, but soldiers from India’s border security forces still use them to patrol the more arid parts of the India-Pakistan border.

BSF camel contigent along the India-Pakistan border. Courtesy: Wikimedia commons

And yet, the camel demographics in Rajasthan are worrying. Data from the latest livestock census shows that by 2019 the state only had about 213,000 dromedaries, down from 325,000 in 2012. There are multiple reasons for this drop.

These include the declining utility of camels for transportation as roads have improved, making motorized vehicles (which are a lot kinder on bottoms) preferable. A 2015 prohibition on camel slaughter for meat has further disuaded some camel herders from continuing in the profession.

The upshot is that it’s more urgent than ever to find alternative ways of utilizing camels if the economics is to support their continued existence. This really shouldn’t be that difficult given what a miraculous creature the dromedary is.

We learned, for example, that camel milk is the new superfood-in-waiting. It is high in essential unsaturated fatty acids and vitamin C. It is better for diabetics than cow milk, given its considerably lower glycemic index. And it is real milk, unlike nut and oat alternatives. It tastes good: rich and flavourful

In Jaisalmer we bought three bars of camel milk chocolate to give to friends in Spain as exotic presents, but ended up eating them long before returning to Madrid - they were that yummy.

Camel milk ice cream, camel hair blankets, camel bone artifacts: there is a whole world of camel commerce out there. Move over camembert, camelbert could be as tasty and healthier.

Camel milk chocolate (and bhang!) shop in Jaisalmer. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

Fantasizing about revolutionizing the world’s food industry jolted my memory about the most interesting, and frankly bizarre, factoid I’d ever been told about camels. It was about 5 year ago at a literary festival in Bali, Indonesia. A young Australian writer I was having a coffee with told me about the million – yes, million! – feral – yes, feral!- camels that apparently roamed the Australian outback.

Australia is certainly synonymous with fascinating fauna: kangaroos, echidnas, wombats, platypii (sp?). But camels?

Camels are about as Australian as polar bears, and yet in the outback, a 6 million sqare kilometre swathe of territory so vast that it is almost twice the size of India, there are so many wild camels wandering about that they need to be culled.

OK, so prepare for the sound of several pieces of the Global Jigsaw - South Asia, Australia, and the Canary Islands of Spain - unexpectedly fitting together at a camel-shaped point in history.

****

The first camel to arrive in Australia was imported in 1840 from Tenerife, which at the time had fewer British holidaymakers and more dromedaries than it does today. Camels were not indigenous to the Canary islands. They were introduced from north Africa in the 15th century.

The idea to import camels to Australia first came from George Gawler, the then governor of South Australia who thought the ungulates could be useful in the dry climatic conditions north of Adelaide. Half a dozen dromedaries were loaded onto a steamship of the Appoline line in Tenerife, although only one survived the journey, arriving at Adelaide harbour on October 12, 1840. The survivor was christened, Harry.

Harry made a moderately successful go of it in his new home, but his career ended in ignominy when in 1846 he was involved in the accidental shooting and death of his owner, one Mr John Horrocks.

Newspaper report on the story of Harry the camel and John Horrocks

A two-decade camel-hiatus followed the unfortunate Harry’s Australian debut. But by the 1860s, the decks of Down Under-bound ships sailing off the coast of north western India – which at the time included modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan - were heavy with the dromedaries that went on to play a crucial role in outback exploration and settlement.

Between 1870 and 1920 as many as 20,000 camels were imported into Australia along with at least 2,000 handlers, who were called “Ghans” after the Afghans, they often, but not always, were. The “Ghans” were mainly Pushtuns, Punjabis, Balochis and Sindhis.

Unloading camels at Port Augusta, 1893. One camel is being winched over the side of the ship, believed to be the steamer 'Bengal', while a number of “ghans” watch on. Courtesy: State Library South Australia

They operated camel trains, sometimes with as many as 70 camels, across South and Western Australia as well as the Northern Territory. Traveling 20-25 miles a day, the camel trains could collectively carry up to 20 tonnes of material on their backs. They accompanied exploratory expeditions and carted wool to ports, barrels of water to drought-hit regions, construction materials, telegraph poles, tea, tobacco and much else, creating crucial lines of supply between isolated settlements.

Even today the luxury train that cuts north to south between Adelaide and Darwin is named The Ghan, in memory of the largely Muslim, South Asian cameleers who played such a crucial role in the development of Australia.

An “Afghan” camel driver with camel train loaded with chaff . Courtesy: State Library South Australia

By the 1930s, once the railways were firmly established, camels lost their importance as pack carriers. Thousands of them were released into the wild. Over the years they have multiplied unfettered. But inevitably they have also come to clash with human outback settlements, destroying water storage tanks and pipelines.

The result is that the government-funded Australian Camel Management periodically culls thousands of animals by shooting at them from helicopters. Between 2009-2013 some 160,000 animals were killed in this gruesome manner.

****

It seems to me that both Australia’s too many camels problem, as well as India’s declining camel challenge, can be met with camelbert. I have dreams for a globally successful camel dairy industry. Think dromedary delights like camel milk gelato, camel milk body lotion, camel milk health supplements for diabetics etc etc.

“Ciao!” from a coquettish camel at the Bikaner National Camel Research Centre. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

Any investors out there amongst the Global Jigsaw community? Spread the word. The camels need us.

That’s all until next week. With love and hopes that you will become a paid subscriber.

Xoxo

Pallavi

Dear Pallavi,

beware of hyping fashions or fads. In 1910, ostrich feathers were the rage worldwide. The suffragettes convinced women to forego them. End of a very important export industry in South Africa within a couple of years.

My suggestion would be more modest: give camel milk to Karni Mata temple near Bikaner - you missed it?

Also: Camels are excellent before a cart: slow, smooth riding. My fondest memory of rolling through the landscape: our heads above the mustard fields.