Hola Global Jigsawers,

Last weekend felt almost epochal; a social light at the end of the long, dark tunnel of COVID. I attended my first, in-person, literary event in close to two years in the Spanish city of Segovia, where an edition of the Hay festival is held annually. I chatted with strangers and dined in crowded rooms filled with writers to the spectacular view of Segovia’s 2000-year-old Roman aqueduct. It was as if I’d suddenly been transported to another dimension, having become used to my home, husband, children and cats as The World.

The aqueduct in Segovia

At the festival, I was part of two panel discussions. One of these was titled “How culture creates wealth.” The moderator was excellent and managed to channel this rather ambiguous topic into several tributaries of interesting explorations. We talked about cultural appropriation and about what cultural characteristics of a society tend to favour economic success.

At the Hay Festival in Segovia discussing culture and wealth with Raphael Minder

But, my first thought when I was invited to speak on the subject was: culture and what wealth? If wealth is defined as money, the cultural life was usually one of meagre material comforts. Think the starving artist of yore, or the struggling journalist of today. If culture were so good for generating wealth, Indian parents would be forcing their offspring to study music and poetry, while warning them off engineering and medicine.

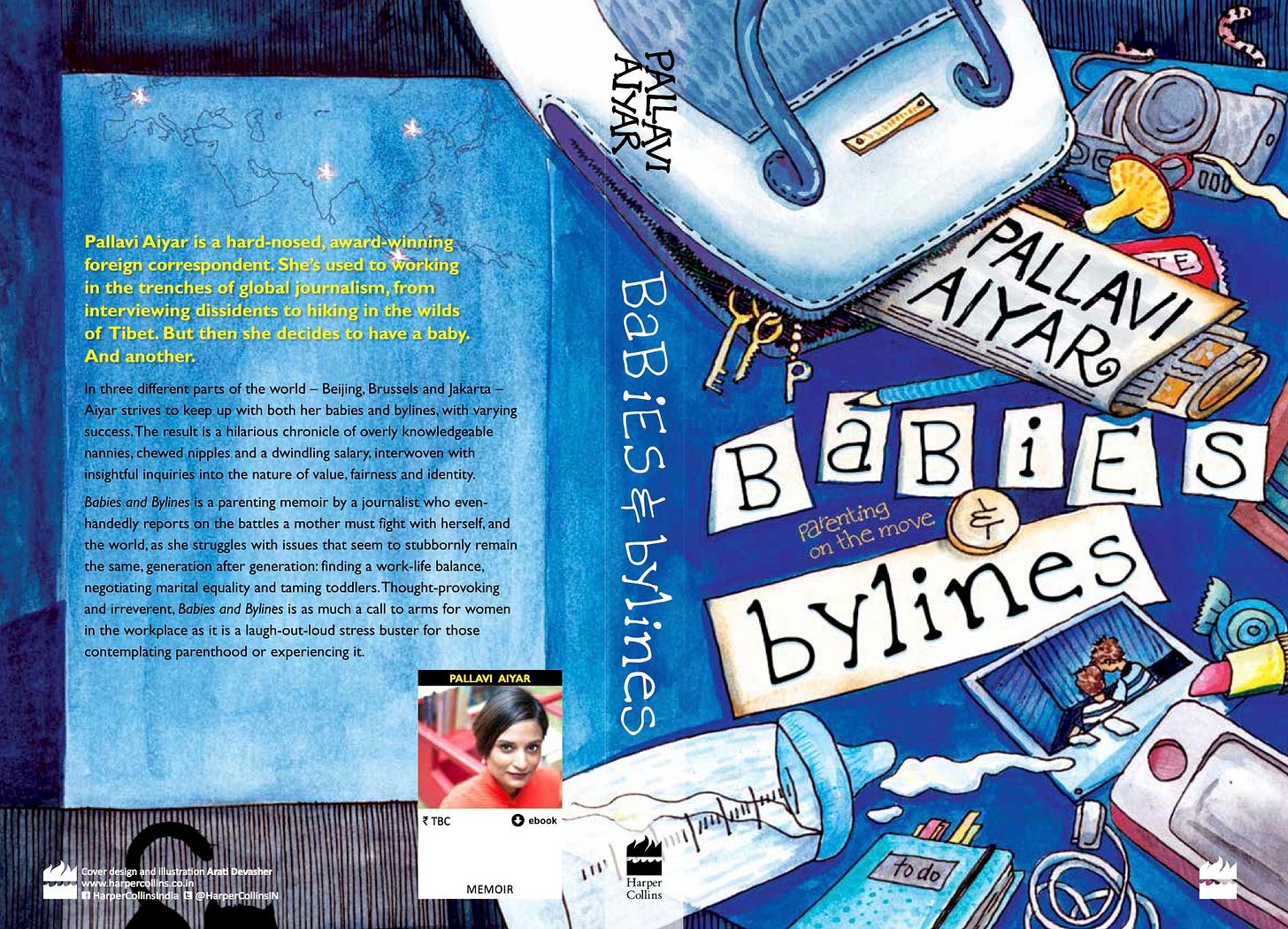

Which brings me to this week’s post about one of the well kept secrets of the writing life: the actual dynamics of privilege and money that underlie it.

Dirty secret

The major enabling factor for me in writing books is the fact that I have a spouse who brings home enough bacon to allow me to write. It feels like a dirty secret. I am a feminist. I am reasonably successful at what I do.

And yet, without financial support from my husband, I would struggle. It feels wrong, but it is the outcome of our collective social choices about what to value and how much of a value to put on different kinds of labour. Writing, housework and parenting - the triumvirate that has dominated the last decade of my life - are all at the bottom of the value hierarchy.

My career as a wealth generator peaked between 2002-2011, when I was a fulltime foreign correspondent for Indian media, at a time when they were advertisement revenue-flush.

Second child nail in the coffin

Then I had a second child. Alice Walker famously said a writer should have only one child “because with one you can move. With two you are a sitting duck.” Well, after Nico was born, I often felt that all I was good for was quacking.

I became “freelance,” so as to be able to juggle all my responsibilities. For those who may be unaware, freelance = poor. I did find the time to write a book however, and as the years went by, a few more. I also devoted myself to motherhood – organising swimming classes, piano lessons, reading out The Lord of the Rings in installments, discussing bowel movements with doctors and on, and on.

I attempted to mentally decouple the idea of “value” from money. Looking after my children and writing books that allowed me to tackle interesting issues in depth, were both valuable pursuits to me. Yet their monetary value was nil and negligible, respectively.

“Value,” money and gender

The problem of “value” lies at the heart of many gender-related issues. The idea that housework needed to be given a monetary value to expose the dependence of the formal economy on the unpaid/unacknowledged labour of caregivers (overwhelmingly women), has a long history. Think the 1970s Wages for Housework Campaign by Marxist-feminists.

But the philosophical conundrum of how “value” is judged remains unsolved. Is value particular or universal? Is it intrinsic to a “thing” itself, or is it something that is awarded by an extrinsic assessor who decides what is in fact of value?

(Full disclosure: I studied philosophy for my B.A. Keep reading at own risk)

Some philosophy

Value can have both a moral and monetary iteration. A diamond is valuable because it costs a lot of money, while kindness is valuable because it is moral. In monetary terms investment bankers are more valued than nuns; but many people would agree that Mother Teresa’s contribution to society has been more valuable than Dick Fuld’s.

The problem is that the moral variant of “value” is subjective, open to debate and cultural relativism. The monetary one seems more objective. The price of a diamond is fixed and quantifiable, but the value of parenting is not.

Most of us unreflexively link the idea of value with money. The role of hard cash in evaluating self-worth is undeniable.

I read the 19th century German thinker George Simmel’s classic text, The Philosophy of Money, on the subject. It describes how money’s role in human society arose from the need to find a supposedly “objective” way of allowing us to compare otherwise incommensurate objects. For example, a haircut, a heart transplant, an African safari, and a book, can all be compared on the basis of their monetary value, despite belonging to different categories of objects.

Yet, although money itself might be a neutral measure, the value system that underlies our money-based economy is far from purely rational or objective. The huge gulf in the earnings of a sanitation worker and a movie actor, for instance, are hardly indicative of their “objective” worth.

But money remains the most reliable and accepted definer of value that we have. As a result, non-financially remunerated work, like that undertaken by stay-at-home parents is devalued, regardless of how critical for the functioning of society it may be.

The time and effort I spend comforting, teaching, dressing, feeding and ferrying the children, is valued. My husband values it, as do the children themselves.

And yet..

And yet, despite all this ostensible valuing, I was never able to fully feel valuable as “just” a mom. Even freelance journalism felt like a more substantial identity, not just because it was financially remunerated (however meagerly), but because it constituted a different kind of value creation to motherhood.

I suspect this is what many women experience. The problem is not that our efforts as homemakers are not valued, but that many of us want to move beyond the domestic realm and to generate value in the public sphere as well. Women want the ability to combine different kinds of work, in the private and public spheres, with different kinds of remuneration, monetary and otherwise.

Writing and gender

An unhappy consequence of the monetary undervaluing of writing is that if, as in my case, the woman happens to be the writer, traditional gender divides become very challenging to slough off. Despite our collective intentions and feminist principles, the silhouette of my contemporary marriage would have been easily identifiable in the mid-twentieth century.

Because I work from home and earn less, I find myself as the primary care giver for our children. My husband is the Provider who spends more time reading the papers, or scrolling Twitter, than doing homework craft projects.

Puzzles aplenty

So, what is the solution to this conundrum? How do we evolve into a society that allows individuals to combine and enjoy different kinds of value, to enjoy an amalgamation of choices, rather than the stark work-life non-choice that is the experience of most people today.

The answer is, as usual, a jigsaw puzzle. Some of the pieces of this puzzle include flexibility in work location, affordable and high quality childcare, enforced parental leave, changes in the socialisation of children. This puzzle is not named ‘having it all,’ but, ‘having enough.’ It’s a wonderful puzzle, even if most of us need a lifetime to assemble it and many of us are denied the chance to complete it.

What further pieces do you think this puzzle has/needs?

There is then also the puzzle of how to bring the monetary value and societal value of good writing into some kind of consonance. One piece of this jigsaw is Substack and newsletters like this one. If you subscribe, it affirms that you value the ideas you consume at least as much as a that extra cup of coffee you pay for.

Do consider upgrading to a paid subscription. And if that’s not possible, please share this post on social media so that we can continue to grow as a community dedicated to crossing boundaries and travelling the world together.

Till next week,

With affection,

Pallavi

I thought this was an honest piece. First we have to overcome the impostor syndrome, then we feel lucky to be acknowledged as the real thing, then we wonder how to pay the bills or guilty that we couldn’t pay them on our own. Of course we would have fewer bills to pay on our own.

And once all that has been figured out, we are left wondering how, and how much, we are valued. But this part is not related to how much we earn per se; it is how much more (or less) other people earn.

To close the loop – it is definitely tied to “culture.” In some countries, people are valued for being highly educated, well-read, fluent in multiple languages, even if not highly paid. In others, these attributes are only valued if translated into higher earning capacity, if not earnings per se.

So within medicine, in the US, pediatricians earn less than cardiothoracic surgeons I am told it is all because of supply and demand. There are fewer CT surgeons than pediatricians. On the other hand fewer people need CT surgery than need pediatricians so one would think supply and demand are still matched. But training to become a CT surgeon takes longer, so that limits supply. Also in the US there is a distinction between cognitive specialties and procedural specialties and those who carry out procedures get paid more. There is a huge shortage of psychiatrists but that has not lifted us off the bottom rung. Then, some psychiatrists earn more than others but it is not for working harder or with more challenging patient populations.

I often think about why professional athletes are paid so much. Because they work so hard and risk their bodies and have short careers? But so do soldiers. I guess because they have more talent? But the talent is used only to create spectacles for millions of less talented people.

So, as you conclude, our only hope is to decouple “value” from “wealth.” Value is about feeling good about what we do and having others feeling good about what we do; going to bed at night (or in the morning after a night shift) in the knowledge that one has done a good day’s (or night’s) work and made the world a slightly better place.

You know the old saying that nobody ever said on her deathbed that she wished she had spent more time doing housework. I suspect nobody said she wished she had made more money, either… or at least, I hope that is true.

Dear Pallavi,

in 1949, the Germans voted on the "Lastenausgleichsgesetz" - a law determining how to share among the citizenry the cost of the lost war. Basically, the haves relinquished 50% of their wealth in favour of the have nots. Great principle - well implemented, for all were unhappy with the outcome. This is the paradox of choice. It does not yield platonic "perfection." It yields a livable burden-sharing - yet remains a burden.

Comparing burdens can be invidious. In the end, however, we donkeys all adjust to the burden.