Hola Global Jigsaw,

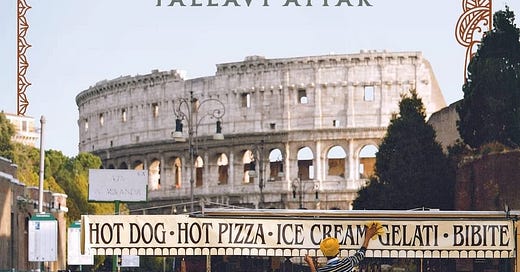

My brother visited me in Madrid a few days ago. He is now in Paris for the weekend, where protests against raising the retirement age seem to be a permanent fixture of the cityscape. They put me in mind of this adapted extract from my book on Europe, New Old World (published as Punjabi Parmesan in India) about the reluctance of Europe’s global labour elite to acknowledge their privilege. Let me know what you think. And if you enjoy it, do order the book.

Or better still, become a paid subscriber to the Global Jigsaw and earn good karma :-)

******

I moved to Brussels, the headquarters of the European Union, in the spring of 2009, following a seven-year long stint in China. For an Indian journalist this was not a promotion. China’s volcanic rise had been the defining story of the twenty first century and the Indian audience had developed an almost pathological obsession with their neighbour. Europe, on the other hand, barely registered a bleep on the Indian media’s radar. The entire continent tended to be reduced to stories about the fortunes of Indian software companies in the United Kingdom.

Relocating to Brussels was a decision driven by my husband, who had recently passed the European Commission’s entrance examination. I was aware that the Belgian capital had a somewhat dull reputation, but I consoled myself with thoughts of waffles and good coffee; cobblestones and cafes. I imagined Europe to be the antithesis of chaotic China: pretty and stable. After years spent choking on Beijing’s polluted air and eating sea slugs at state banquets with false appetite, perhaps a relaxing, laid-back assignment in Europe was what I needed.

Perhaps, but it was not to be. The timing of my move was such that before long I was once again in the eye of a news maelstrom. From the “Rise of China,” I found myself witness to the “Decline of Europe.” The stories I reported as the Europe correspondent for the Business Standard over the next three years were filled with the one word that came to define Europe’s current state most commonly, yet confoundingly: crisis.

On the streets I witnessed demonstrations by disgruntled workers holding up placards that read: “say no to the crisis” as if the “crisis” were cocaine.

From TV newsrooms to the corridors of the European Commission, the term “crisis” reverberated, abused as much as it was used.

Coming from China, I was miffed at all the hand wringing. Walking around Brussels’ boulevards’ with their stately fin-de-siecle maison de maitre, little appeared amiss. There was no famine No stench. No tanks in the Grand Place. From my Chinese-Indian perspective, Europe’s crisis was a strange creature: a nice-smelling, well-dressed, bucolic kind of crisis.

Furious protests outside the EU headquarters were part of the scenery. At first, I found these curiously exhilarating. After years of reporting in China where demonstrations were either banned outright or stage-managed into insignificance, there was an allure to the pageantry of irate dairy farmers urging their cows to moo at policemen, and the anarchy of fishermen throwing their daily catch at eurocrats. But once the initial luster wore off, I no longer saw these protests as potent examples of people power, but as blackmail, however unwittingly, by the elite of rich Europe’s workforce.

These were not malnourished coal miners from northeast China whose families were dying from lung cancer. These were not subsistence peasants from Sichuan whose land had been arbitrarily appropriated by corrupt local government officials. These were not tribals from India’s forests whose women had been raped and leaders murdered by mining company bosses.

They were usually trade union-protected workers fighting any loss of their substantial entitlements no matter the cost to their countries as a whole. Striking dockworkers, refuse collectors, pharmacists, newspaper vendors, taxi drivers: everyone was in on the Euroballoo. I wondered if they realized just how privileged they were.

The people of western Europe had been very fortunate in recent history not because they somehow boasted superior moral fibre; nor because they were innately more innovative, clever and efficient than citizens of the developing world, but because they had been born in the right countries at the right time in history. In effect, they’d chosen the right parents.

All the talk of Europe’s decline had a corollary in the rise of other parts of the world that had long been deprived and marginalised. If Europeans had to work somewhat harder for their money, resulting in a modest leveling out of global inequalities, surely this was not a catastrophe. Perhaps, it was time for European policy makers to uncrease their furrowed brows and raise a toast to the great benefits to humankind at large, that Europe’s relative decline indicated.

As the economist Arvind Subramanium points out, despite the financial crisis that has plagued the rich countries of the West since 2008, the period of accelerated global economic growth that began in the mid-to-late 1990s, has mostly survived. Prosperity in fact continues to spread across the globe at an unprecedented pace. From a global perspective, the post 2008 period remains a “golden age of global growth”.

This rebalancing of economic power means that for Europe to remain competitive some belt tightening is necessary. Europeans have to retire a few years later than they have become used to doing. They need to learn new languages to find employment further away from their hometowns than they might ideally prefer.

I found many people in Europe who were willing to embrace these changed circumstances. But they were rarely Europeans. Instead it was immigrants who were taking up the gauntlet, despite concerted efforts at preventing them from working as hard as they would have liked to.

I had never heard the word “work,” made to sound like a term of abuse before I visited the rapidly shrinking cohort of Jewish diamond merchants in the port city of Antwerp, in May 2009. Antwerp is the center of the global trade in diamonds, and 80 percent of the world’s rough diamonds and 50 percent of all polished stones change hands here. For decades, the trade was controlled by the city’s orthodox, largely Hasidic Jewish community, their austere black frock coats and tall hats in stark contrast to the glittering minerals that occupy their attention.

But the last two decades have not been easy for this community, and the younger generation has been leaving en mass for Israel. It is not anti-Semitism driving them away, but the intense economic competition unleashed by the forces of globalization, as represented by the rise of the Indian Guajarati diamantaire.

Today up to 70 percent of Antwerp’s lucrative trade in diamonds is in Gujarati hands, and people with names like Mehta and Shah, rather than Epstein or Finklelsztein, rule the city’s diamond quarter. The first wave of Indians arrived in Antwerp in the 1970s. They started at the bottom of the business, trading low quality roughs of little interest to the established diamantaires. Three decades on, the Indian community in Antwerp consists of around 400 families. Companies that began as one-man operations dealing with a handful of diamonds, have been transformed into billion-dollar-plus global enterprises, employing thousands of workers with factories and offices dotted across the world.

I was curious to find out just how Indian Gujaratis had come to be so successful and spent a few hours talking with members of the Antwerp Indian Association, a social club with over 2,000 members all of whom were connected to the trade.

Santosh Kedia, an avuncular trader who was chairman of the association, explained that the Indians had been helped by links to diamond-processing facilities in cities like Surat in Gujarat, where skilled labour is abundant and costs are as little as a tenth of the European equivalent. ‘For us, sending rough diamonds to India for processing isn’t outsourcing as much as homesourcing,’ he said.

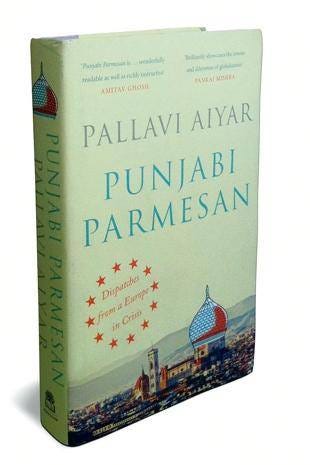

Later, I visited the offices of Rosy Blue. The company billed itself as the world’s largest diamond manufacturer and was headed by a beak-nosed, bespectacled Gujarati, Dilip Mehta. Mehta had been bestowed with the honorific title of “Baron” by the Belgian king in 2006 for services rendered to the country. He looked coyly proud as he described his billion-dollar company’s operations in fourteen countries around the globe.

He’d grown up in Bombay but was sent by his family to the city of Surat after having dropped out of college. At the time, Surat was an up-and-coming diamond-polishing center, and Mehta had worked on his family factory’s floor. He’d bicycled to work and cooked for himself. ‘There was none of this,’ Mehta said, indicating his plushly appointed office.

Mehta moved to Antwerp in 1973, following his father and brother who had established a presence in the city a few years earlier. They made a living buying rough stones that they sent back to Surat for polishing and sold at a small profit back in Antwerp

Indian diamantaire, Dilip Mehta. Pic credit: Pallavi Aiyar

Mehta said that the key to his eventual success was his willingness to work as hard as was necessary to beat the competition. ‘The Jews just couldn’t withstand our competitiveness,’ he shrugged. ‘We are married to our business. We will work at night and on the weekend. And we are willing to work this hard even for small margins.’

For Antwerp’s Jewish community, the Indian takeover had proved unstoppable. Antwerp used to boast around 25,000 specialist polishers and cutters only a few decades ago, many of whom were Jewish. This number was now down to less than 1,000.

My final interview that afternoon was at the offices of one of the larger Jewish-owned diamond companies still in business, Pinkusewitz diamonds, an outfit that employed 3,500 people. I met with its head, Abraham Pinkusewitz, a Hasidic Jew with a great white beard and intense, deep-seated eyes. He looked uncomfortable throughout the meeting despite the smiling, coffee-offering presence of his public relations manager, Eli Finkelsztein.

On Hovenierstraat in Antwerp (the diamond district). Pic credit: Pallavi Aiyar

Pinkusewitz’s children had moved to Israel and were loathe to return. ‘My father’s name used to mean something in this city,’ Pinkusewitz said in his slow, deliberate manner. ‘Now it will all end with me.’

When I asked him how the Indians had edged the Jewish community out of their primacy in the trade, he was gruff. “We have our family. Our religion. Our studies. So, we cannot be open at night and the weekends, unlike the Indians.” Finkelsztein had put a restraining hand on Pinkusewitz’s arm, but the old man had shrugged him off. ‘The Indians work too hard,” he’d spat. “Diamonds are their life and they won’t stop at anything to grab customers.”

This was not the first time a Jewish community in Europe had been forced out of a profession they had painstakingly carved out as their own, and it was difficult not to feel some sympathy for the predicament faced by the Jews of Antwerp. But the latest ousting from the diamond trade at the hands of the Gujarati Indians was not a pogrom. Rather, it was a clash between an old order and a new one – a collision being mirrored across Europe in diverse ways, as once settled power equations are recalibrated. This is a world of intense economic competition from the mammoth old-new challengers of Asia – a world of interconnectedness, new technologies and new fluidity.

The allegations Pinkusewitz made against the Indians – what he deemed as “unfair” competition because of their willingness to work long hours – were, ironically, charges leveled over the centuries against the Jews themselves. And yet Pinkusewitz had displayed scant self-reflexivity as he espoused what was a common European sentiment towards the continent’s new immigrants.

This accusation - that immigrants work too hard for too little – is commonly made, up and down the economic value chain, as much against Indian diamond merchants as against Chinese factory workers. Having spent my life in India and China where, chi ku, or “eating bitterness,” as the Chinese call it, is an unquestioned virtue, I found such antipathy towards hard work startling.

I had first encountered this attitude years ago when reading about the Spanish town of Elche, a traditional bastion of the shoe industry. Workers in upstart Chinese shoe factories in Elche worked longer hours than what was the norm in Spain. Local workers set two Chinese-owned warehouses and a delivery truck on fire in protest in 2004. An article in the Christian Science Monitor at the time explained the outburst against the Chinese had to do with the feeling amongst Spaniards that the economic practices of the Chinese “threaten age-old social customs, employment norms, and labor relations.” Their single-minded desire to make money “clashes with traditional values that privilege family, friends, and leisure over moneymaking.”

But given that only 50 years ago poverty had regularly forced Spaniards to emigrate out of their countries, the social customs and values that present-day Europeans seem to regard as so integral to their culture, are not particularly “traditional” or “age-old.” They are in fact rather modern.

Contemporary Europeans have been enjoying the fruit of the long battles waged by the labor movement well into the latter half of the 20th century. The social contracts that they consider sacrosanct are a hard-won privilege, which have ossified into entitlements. The historical amnesia that allows Europeans the conceit that their culture is somehow inherently superior to that of grasping and crude Asia’s, is rarely acknowledged.

*******

Hope this provokes some debate. Let me know what you think:

Hasta pronto,

xo

Pallavi

Wonderful post. I keep missing 'exactly, I echo that' paragraph after paragraph..

As I often say as an Indian living in Europe (Spain) with all the privileges that i will remain grateful for - my work-life balance is a lot of work and I do not think or certainly do not know, if that will be the same for next generation.

I think in short, this note from James Clear's newsletter seems appropriate - "Ambition is when you expect yourself to close the gap between what you have and what you want.

Entitlement is when you expect others to close the gap between what you have and what you want.".

Continue to look forward to more posts/global jigsaws..

Hello Pallavi, that was a very interesting piece, thank you. I'm an Indian living in Paris and I must admit that when I make the comparison between labor rights in France vs. labor rights in India, and work-life balance in the two countries, I do feel like Europe has got it right. It seems to be the last place in the world where your life can be about more than just work, where you have the space to develop your other interests and spend time with friends and family in a way that few can afford to in India without inherited wealth. And my sense is that it is the gradual diminishing of this, the consequence of globalization and this particular extreme stage of capitalism, is what people are protesting against.

I think your point about Europeans today forgetting (or perhaps just not knowing? History lessons tending to leave out important information!) about the same hard work done by their ancestors that got them to where they are today is a very interesting one but the presentation of the idea seems to suggest that Europeans don't believe in hard work, or that somehow it's virtuous for your job to take over your life - I don't think the first is necessarily true, and the second is definitely up for debate in my view. But thanks for making me think on a Sunday morning! Will definitely pick up a copy of your book :)