Finding home in New York through Indian Classical Dance

Guest post by Radhika Jha

Dear Global Jigsaw Friends,

Today, I bring you a guest post by dancer, author, and professional peripatetic, Radhika Jha, on finding home in New York through Indian classical dance. She explores the possibilities of reinvention, and of staying true to traditions while breaking them at the same time. You can watch a video of one of her performances, here.

Pic: Radhika Jha

I myself learned the Bharatanatyam form of Indian classical dance for many years as a child, giving it up at the age of 14. In my early 30s I returned to being a student for a while with a Chinese teacher, Jin Shan Shan, in Beijing. Amigos: the world is indeed a global jigsaw.

I hope you enjoy the post and share it widely.

Also, please do consider switching to becoming paid subscribers. The anti-purity celebration of admixture that is this newsletter, needs not just your good will, but also your patronage. 🙂

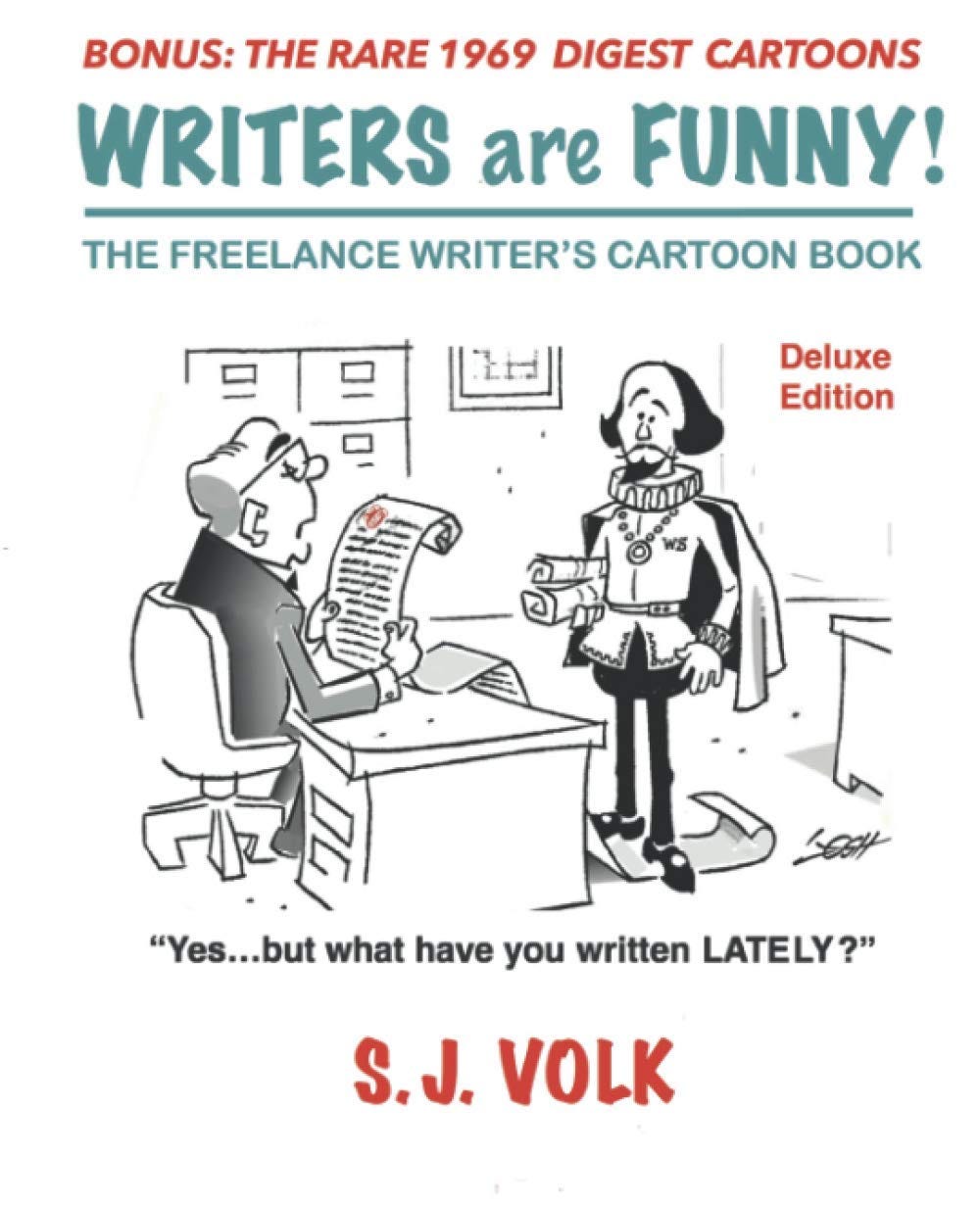

Buy this book ☝️, but also:

Dance inside me

Every city has its own secret perfume. After a while, when you have lived there long enough, the scent infiltrates you and makes you its own.

One of the features of my life as a diplomatic spouse is that every four years, I must uproot myself and move. I have done this four times, and this last time landed me in New York, eight months ago. What is funny about New York is that everyone has an opinion about it. Those who live here hate it or love it. But no one wants to leave it.

What is this city’s secret scent, I ask them? Why do people want to stay in this crowded, dirty, noisy place? The answers you get are disappointingly similar – it is multi-cultural, it is global, there is such a special energy here. All these answers are true. But none of them quite manage to explain, to my satisfaction, the stickiness of the place, its unique fragrance.

At first, I thought that perhaps it didn’t have one; that there were just too many people from too many different places and backgrounds colliding randomly to allow it one. But, as the months rolled on, an answer began to emerge: New York is a place where people come to forget their past. They come here to re-imagine and re-fashion themselves.

If humans were spiders in a web, then coming to New York would be the equivalent of cutting all but one thread. Could a spider be happy, dangling by a single string? I thought that I wasn’t that kind of spider. But just as I was about to give up on the place, I found the connection I was looking for – in a most unexpected place - at an abhinaya festival in New York.

Abhinaya is the term that refers to the narrative aspects of Indian classical dance. It involves the use of codified facial expressions, combined with hand and body gestures, to tell a story. But there is also a degree of improvisation allowed within the codified parameters. Hence its difficulty --for its mastery goes beyond simply harnessing the body. It also demands the use of the imaginative and the emotive powers of a dancer.

I have been studying various forms of Indian classical dance since I was nine years old. In India, dance forms evolved in temples and courts well before the birth of Christ, around the same time as dance developed in Greek temples.

The British, who ruled India for about 200 years until 1947, however, saw these dances as quasi-pornographic and immoral. Dancing was banned from temples and the patronage of dancers ceased.

In the early 21st century, interest in the classical dance forms revived with the birth of the anti-colonial, nationalist movement. Today, there are five main styles of classical dance, and a whole new generation of, mainly middle class, urban dancers. I am one of them and have performed as a professional Odissi dancer, as well as taught this style in Japan and China.

But secretly, I’ve always wondered if it were possible to use the incredible storytelling tool that is abhinaya to bring alive narratives that did not focus on the standard set of stories centering on the exploits of Hindu Gods and Goddesses such as Shiva and his consort Parvati, Krishna and Ganesha.

A few weeks ago, I found myself attending an Indian classical dance performance at the Symphony space on the upper West side of Manhattan. I expected to feel about it, the way that I feel when eating Indian food outside India – somewhat unsatisfied at the end. Indian food abroad always lacks something in its flavour. But because I knew the festival curator, Maya Kulkarni, I felt she had to go. Kulkarni is a doyen of Bharatnatyam, a style of dance that is a cousin of sorts, of the Odissi that I perform.

Promotional image for the performance

The festival was focused on abhinaya. It featured four pieces by four dancers, one from each of Indian classical dance’s main avatars: Kathak, Mohiniyattam, Odissi and Bharatnatyam.

The first piece, “I dance thus I am,” was an autobiographical piece performed and choreographed by Jin Wong, a Korean Kathak dancer. The story was simple – a woman finds herself through dance, in this case Kathak, and then she finds another kind of dance hidden inside herself that is different and cannot be contained within the strict rules of Kathak. So, she breaks free and allows herself to dance that inner dance.

The performance began with the primordial rhythm of the heartbeat and then grew more complex as the feet found expression in the intricate rhythms of Kathak. In what was the most stunning and original part of the performance, the music changed, growing simpler again, yet more insistent, an endlessly repeating six and a half beat cycle, which by its very nature is open ended and haunting.

The dancer’s movements slowed, her gaze turned inward, and she began to move more loosely. The movements were like spasms almost, resembling something involuntary and instinctive, rather than the polished and aesthetically pleasing.

My breath caught. It is every dancer’s dream to find oneself in dance, while simultaneously breaking the mould of what one has been schooled in. But I’d always presumed that Indian classical dance styles were too rigid to allow for this. I exulted in having been proved wrong.

The second piece, a Mohiniyattam abhinaya, was about a woman remembering her night spent with the Hindu God, Krishna. It was the perfect foil to the first performance, being both extremely traditional and beautifully executed. The young dancer seemed to have been marinating in the rhythms and juices of Kerala, the birthplace of Mohiniyattam, forever. She danced so beautifully, so authentically, that I felt I was watching a performance in India, or eating a meal at home in New Delhi.

The third dance, “Impossible Longing,” while in the Odissi style, was not set to a classical poem. It was created, written and choreographed by Maya Kulkarni. The story, a fable about vanity, was in essence simple: a naughty peacock is slightly bored one afternoon and looks around for something to amuse itself with. It sees a rain cloud and gets into a conversation, only to realize that the rain cloud is very boastful.

The cloud brags about how without the rain it brings, life itself would come to a halt. The peacock decides to teach it a lesson in humility. “I have a secret,” it tells the cloud. “I know where the most beautiful creature in the universe is. She is exquisite, fast as fire and just as deadly. You will be blinded by her beauty. Her name is lightning. But don’t go too close, or you will perish.”

The cloud is agog and soon hunts down the lightning who is all the peacock described and more. He chases her across the skies and finally grabs her in a fierce, lustful embrace. Only to be turned into nothing.

The dancer, Kaustavi Sarkar, was superlative in performing Kulkarni’s demanding choreography. The story sprang to life because the feelings of each character were writ large over every gesture. In classical abhinaya, the dancer is bound by the text and compelled to enact each word of the poem, literally. This is how it has always been done.

But at this performance, the dancer was able to break free of normative strictures. She embodied the story, the emotion, the characters. I was transported, and when the cloud greedily embraced the lightning and was turned into vapor, I didn’t know whether I was glad or sorry for the poor besotted cloud. I was in the story.

The final Bharatanatyam piece, performed by Mesma Balsare, was also choreographed by Maya Kulkarni. It was a portrait of Medea showing her different aspects - queen, goddess, lover, mother, murderess. This was really stretching the packet, I thought, wondering how Indian classical gestures would be used to show a Greek character.

Pic: Mesma Balsare

But once again, the imagination of the choreographer was such that she was able to create gestures and movements that were removed from conventional Indian classical style, and yet of it. I watched in spellbound horror as Medea played with her children, loving them, and hating them (for they were also the children of her lover Jason who had so cruelly forgotten her), before finally killing them.

My eyes opened to how Indian classical dance is not just able to be contemporary, but global.

I have seen Maya Kulkarni dance for over thirty years. She is an amazing dancer, but choreography of this daring, I think, would not have been possible had she remained in India. Perhaps then she would have been content to be known as a great dancer and teacher. But she wouldn’t have taken the risk of doing something so different, pushing the boundaries till there were none left. That needed New York.

The secret this city carries in its belly is that it lets you become something new, something stronger and more daring than what you were before. That is, if you can survive it.

*****

That’s it for the this week, folks. I hope you enjoyed this foray into the world of dance. Do share and subscribe and spread the love.

Until next week,

Virtual hugs,

Pallavi

Eound Rajihkas story fascinating; it says a lot fot NYC that she got the inspiration to give Indian classical dancing a new life, making the sories appeal to non Indians as well. The peacock and the cloud sounds delightful

What a great write-up about what must have been a scintilating performance.