Hola GlobalJigsaw family,

I hope February has begun well for you. It’s been unseasonably warm in Madrid (no complaints from me) and I’m already anticipating Spring (and missing Japan as is inevitable when thinking of spring).

This week’s post is an introduction to the marvelous melange of Mughal miniature paintings. It is a world of aesthetics from which a star burst of thought provoking lines of inquiry emanate.

Mother and Child with a White Cat. Circa 1598. Attributed to Manohar (active ca. 1582–1624)or Basawan. The Met, New York

Syncretism is a state of mind. One that is greedy for abundance and curious about admixtures. Given the intellectual/political silos the contemporary world is determinedly divided into, the idea of syncretism can seem almost childlike: unlettered in hard realities, innocent of pragmatism.

But you need only scratch beneath the surface of most nations to discover that our histories have in fact been hybrid. Examine the language of Spain and you excavate Arabic. Visit an Islamic boarding school in Indonesia and you end up teaching a room full of boys with Hindu names. Eat a plate of chicken curry in India, and you sniff out a food trail leading to the Americas.

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, had described India as an “ancient palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously.”

Each succeeding layer blended into something greater than the sum of its parts. This tendency of culture to agglomeration is certainly not unique to India, although until recently, India had arguably resisted the urge to purge and purify more successfully than its fellow pieces of the Global Jigsaw.

A recent visit to the National Museum in Delhi, hit this point home to me with an aesthetic sledgehammer. I felt the initial few blows as I wandered past the Greco-Indian Gandhara statues.

Nicolas Arias poses in front of a Gandhara sculpture at New Delhi’s National Museum. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

But what really slammed me in the solar plexus was the section on Mughal miniature art.

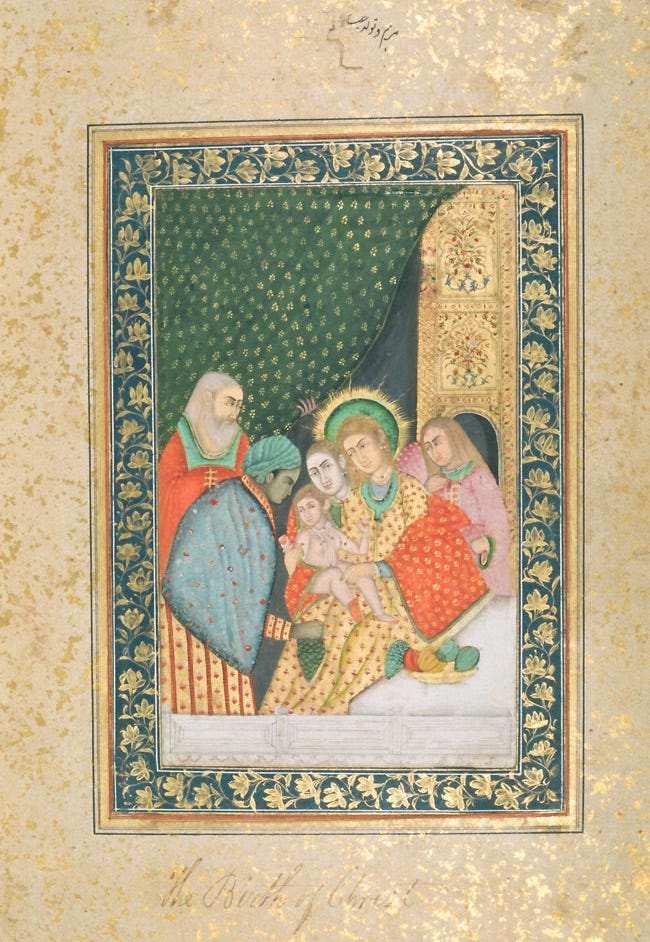

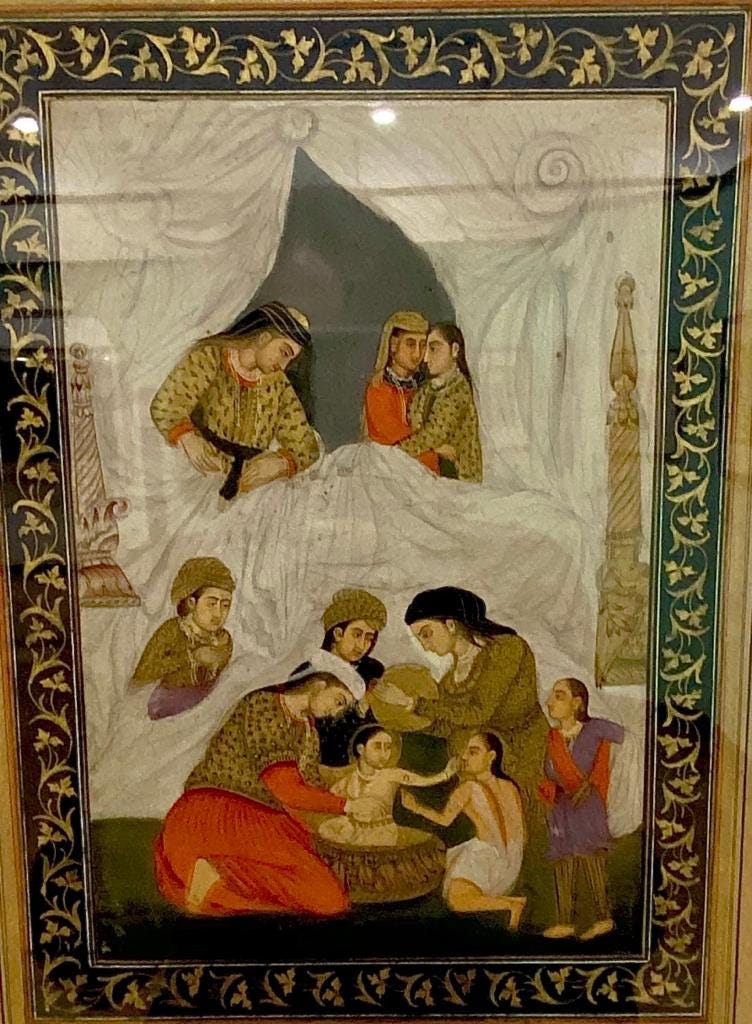

Nativity, circa 1720 A.D., National Museum, New Delhi

These are paintings that were commissioned by Muslim rulers in India (the majority between the mid 16th and 18th centuries) and executed, for the most part, by Hindu artists, often under the tutelage of Persian masters. They depict myriad scenes from court life, the natural world, and intriguingly, even the Bible.

The Nativity. Mughal, Muhammad Shah period. Circa AD 1720-25. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

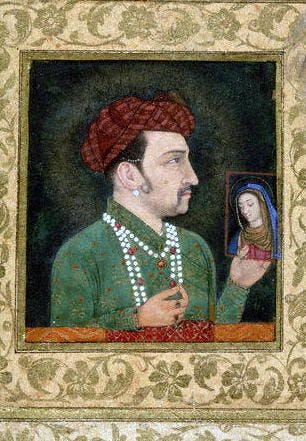

Mughal Emperor Jahangir. 1605-27. Holding the picture of Madonna. Artist: Abul Hasan. Circa AD 1620. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

The Mughals

The Mughal dynasty held sway over much of the Indian subcontinent for about 200 years, starting from 1526. At the peak of its power in the mid-17th century, it was arguably the most powerful force in the Islamic world, ruling over 100 million subjects. The association of the Mughals with power is evident in the modern usage of the word “mogul.”

Unlike some of the Islamic conquerors who had come galloping into India in previous centuries to maraud and sack, the Mughals established their home in India, becoming an integral part of the palimpsest that Nehru referred to. In modern parlance, they became Indian passport holders, although some of them were perhaps closer to OCIs, with toeholds in Uzbekistan and Iran.

More than any other Islamic dynasty, the Mughals put aesthetics and a love of the arts at the center of their imperial identity. They tempted some of the great Persian masters to their courts, where they also hosted scholars, mystics, musicians, and poets.

During the reign of Akbar the Great (1556-1605), in particular, an intellectual flowering took place. Debates on theology and metaphysics were encouraged at court. And a great number of illustrated translations of books between Persian and Sanskrit were commissioned.

The Mughal miniature art form that resulted was heavily figurative and in complete dissonance with ultra-orthodox Muslim opinion, which objected to the depiction of the human form.

Akbar on painting

"There are many that hate painting," Akbar told his biographer Abu’l Fasl. “But such men I dislike. It appears to me as if a painter had a quite peculiar means of recognising God; for a painter in sketching anything that has life, and in devising its limbs, one after the other, must come to feel that he cannot bestow individuality upon his work, and is thus forced to think of God, the giver of life, and will then be increased in knowledge."

Akbar’s attempts to reconcile the different faiths and philosophies of the peoples of his empire are legion. He promoted Hindus in his civil service and ended the religious tax paid by non-Muslims under sharia law. Christianity also fascinated him.

Akbar and the Jesuits

In 1580, Akbar invited to court a party of Portuguese Jesuits from Goa. They were permitted to establish a chapel and were astonished when the Mughal emperor prostrated himself in front of two paintings of the Madonna and Child. He also joined in the Jesuits' Christmas festivities, which involved setting up a crib in the palace with placards proclaiming, "Gloria in Excelsis Deo," in Persian.

By the end of Akbar's reign, a mural of the nativity even filled a wall of the emperor's private chamber, and miniatures and ivory plaques of Christian subjects had become a major part of the Mughal karkhana’s (atelier) output.

But these were Christian images wrought anew, domesticated. The results cock an artistic snoot at purists.

Mary as a Hindu noblewoman and other delights

There are images where the Virgin Mary appears wearing a bindi, or with henna-dyed fingers, in the manner of an aristocratic Hindu lady. At the same time, some European-influenced miniatures depict Mughal emperors with their heads encased in haloes à la Byzantine icons.

Akbar holds a religious assembly in the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) in Fatehpur Sikri; the two men dressed in black are the Jesuit missionaries Rodolfo Acquaviva and Francisco Henriques. Painting by Nar Singh, circa 1605.

Madonna and Infant Jesus, circa 1620-1630, From the Muraqqa of Nana Phadnis. This painting is a highly Indianised versions of a European print of "The Holy Family with St. Anne & Two Angels" by Aegidius Sadeler.

Today, even as the political climate in India has turned hostile to its own history, attempting to paint India’s Mughal heritage solely in terms of foreign invasions whose influence must be purged, its own museums stand testament against such a view.

Moreover, Mughal miniatures with their colourful portraiture, diverse subject matters, hybrid-styles and technical sophistication are an aesthetic refutation of the Wahabi interpretation of purist and austere Islam. Much Islamic art and architecture was—and still is—created through a synthesis of local traditions and more global ideas. It encompasses works created by Muslim artists for patrons of any faith, including—Christians, Jews, or Hindus—and the works created by Jews, Christians, and others, living in Islamic lands, for patrons, Muslim and otherwise.

I hope you enjoyed this piece. Please so consider becoming a paid subscriber to The Global Jigsaw so that I can keep writing it and helping us understand the many wonderful ways in which the world fits together.

Until next week.

Pallavi

PS: If anyone is interested enough to follow up further, I highly recommend this instagram account devoted to the details of Mughal miniatures: @niraamish

thank you for this. A breath of fresh air, great article!

Hi Pallavi Ma'am, I am doing my Master's thesis having this article in my select bibliography. Thank you very much for your work. Is there anyway that I could connect with you?