Greetings: the clan of the Globaljigsaw

I am on holiday with my family this week. We’ve been visiting the coast of Andalucía. It’s so magical, partly because it’s one of those great crossroads - between Europe and North Africa in this case- that inevitably evoke awe and history. And because of Gibraltar, Great Britain keeps popping up on the horizon too. I will write about this geographical fascination next week.

For this week, here’s a story from my new book, Orienting: An Indian in Japan, about an elephant named Indira and her role in furthering post-war Indo-Japanese relations.

**********

One further character of heft, quite literally in this case, that it would be remiss to omit when talking of post-war India-Japan bonhomie was an elephant. In 1949, Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first prime minister, engaged in a deft bit of pachydermic diplomacy by dispatching an elephant named after his own daughter, Indira, to Tokyo’s Ueno zoo as a gift ‘to the children of Japan’. The elephant went on to become the zoo’s star attraction and an enduring symbol of Indian friendliness towards Japan.

But this entire episode was occasioned by an incident that was achingly tragic and also involved former ambassadors of India: the elephants Tonki and John. A male and female pair, they had been acquired by the zoo from India in 1924. They were joined by a third elephant, Hanako, from Thailand, about a decade later.

During the Second World War, it was resolved to kill the zoo’s ‘most dangerous’ animals to deal with the possibility of them escaping during an air attack. Consequently, in 1943, the three elephants were starved to death. There are accounts of how Tonki, who lasted the longest of the three, desperately performed tricks every time a human passed his enclosure, in the vain hope of some food.

In Japan, the gruesomeness of this slaughter is often glossed over, although there are some anodyne accounts made palatable for children. For example, the enormously popular picture book Kawaisōna Zō (Faithful Elephants) was originally published in 1951 and remains in print.

In general, the sad fate of Ueno’s wartime elephants was largely eclipsed by the arrival of Indira, whose journey to Japan from the jungles of Mysore began in a petition submitted to the upper house of the Japanese Parliament by two precocious seventh-graders. The students were sad that they were no longer able to see an elephant at the zoo and asked whether a new one could be procured. Their petition snowballed into a public campaign.

In the end, the Tokyo government collected over a thousand letters from children, all addressed to the prime minister of India, pleading with him to send them a replacement elephant.

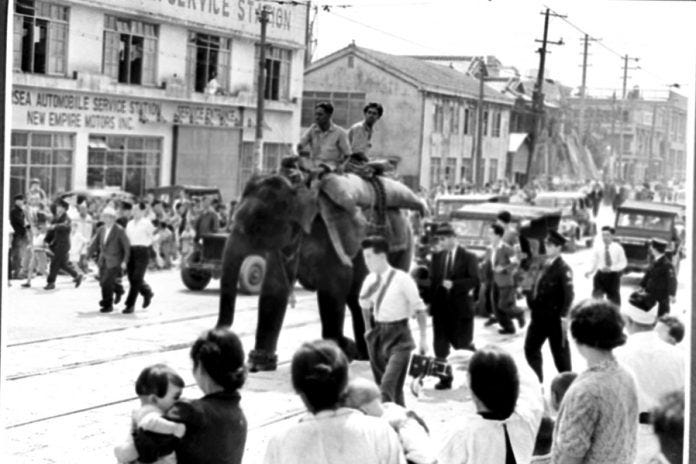

Nehru acquiesced, and Indira’s arrival at Ueno on 25 September 1949 caused much excitement in Tokyo. The zoo was packed to capacity, with thousands of people trying to glimpse the new elephant. Tadamichi Koga, who was the head of the zoo at the time, later said that receiving Indira was one of the happiest moments in his life.

Since she could only follow commands in Kannada, her ‘mother tongue’, Indira’s Japanese handlers, Sugaya and Shibuya, had to learn how to communicate with her from the two Indian mahouts who had accompanied the elephant from Mysore. It took them two months, but they were eventually able to establish a rapport with their charge. In 1957, Indira had an ‘in-person’ meeting with Prime Minister Nehru and her namesake Indira Gandhi, when they visited Japan. The event was widely covered in the media.

By the 1970s, the elephant’s stardom had somewhat dimmed, particularly after a couple of giant pandas from China arrived at the zoo in 1972. Nonetheless, Indira remained an object of affection, and when she died in 1983, Tokyo’s governor, Shunichi Suzuki, paid tribute to her. ‘She gave a big dream to Japanese children and played a good role in Japan–India friendship for more than thirty years,’ he said.

Over the centuries, the Japan–India story had featured a motley cast of characters: travelling monks, fugitives, cooks, poets, movie stars and elephants. Attempting to tie them all neatly together for the purposes of a concluding paragraph feels somewhat disingenuous. It might be best to end this section with the letter that Jawaharlal Nehru addressed to the children of Japan when he sent them an elephant.

‘Indira is a fine elephant, very well-behaved,’ he wrote. ‘I hope that when the children of India and the children of Japan will grow up, they will serve not only their great countries, but also the cause of peace and cooperation all over Asia and the world. So you must look upon this elephant, Indira by name, as a messenger of affection and goodwill from the children of India. The elephant is a noble animal. It is wise and patient, strong and yet, gentle. I hope all of us will also develop these qualities.’”

************

I hope you enjoyed this extract. The book is available on Amazon and in bookshops in India. The Japanese translation will be out, and available in Japan, by the end of the year.

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please do consider subscribing. Content is often free to read on the Internet, but it is not free to produce. It is this imbalance that is partly to blame for the “crisis” of media that people love to bemoan, but rarely act to rectify. I think part of the reason is that most of us don’t know how our individual actions might bring about the change we want.

Supporting independent media, and micro-media, like this newsletter is one concrete, and easy, way to do so.

Even if you do not wish to subscribe, do help grow our following by sharing this, and other stories on the Global Jigsaw, with your networks.

It is much appreciated. Truly.

Ciao, till next week. I am always eager to hear from you, so do write in with comments, suggestions, stories, gossip :-)

xoxo

Question: are there any "gifts" in history from Japan to South Asia or beyond? We have had a lot of chinoiseries and other export goods out of China in the past (see shipwrecks). I'm not aware of anything comparable out of Japan - until the Japonisme movement during Meiji.