Indonesia's Islamic rain shamans

Hotel bills for outdoor events in Indonesia often include fees for rain shamans

Dearest Global Jigsawers,

Many of you have been with me on this weekly journey of connecting the dots across the world for almost a year. We’ll be celebrating our first birthday in February. I want to begin with an enormous thanks for your pointing-out-of-typos, subscriptions, comments, shares and what not. Muchisima gracias!

I am off to India next week, for 6 weeks. This is after a gap of 2 years!

I’ll be recording the audio book for Orienting, doing a few in-person events around the book, and also taking a short vacation in Rajasthan with the family– Bikaner, Jaisalmer and Jawai.

During this time, The Global Jigsaw will be on a hiatus of sorts. I will publish guest columns and book extracts, but my regular posts will only return mid-January.

I already have some essays planned for 2022. I’ll be looking at race as caste in the United States, migrant worker poetry in China and the role of flamenco in “mainstreaming” Spanish gypsies. You can also look forward to several travelogues including one about leopard spotting in Rajasthan.

Wish me luck for my first long distance flight is ages…and for a return “home,” something that can always be a bit fraught, but even more so after such a long gap.

On to this week’s post for which we travel to Indonesia and the role played in the archipelago by rain shamans.

*****

Babey’s face was gnarled, yet implacable, like an aged banyan tree. He smoked compulsively through a wracking cough, putting down his cigarette only occasionally to wipe the sweat off his brow. When we met a few year ago in Jakarta, the heat was stifling.

The rains had been late that year, a fact that weighed on paunchy, sixty-five-year-old Babey’s mind even more than on the average Indonesian’s. This devout Muslim was also a rain shaman, or “pawang hujan”, as such weather wizards are known in Indonesia.

I had first heard about pawang hujan while organising my ten-year wedding anniversary celebration on the island of Lombok. I’d wanted a beachside barbecue so that we could dine with our guests under a star-bejeweled sky. But the date was bang in the middle of the rainy season. My concerns were dismissed with an airy wave of the hotel manager’s hand. “Don’t worry,” she’d said confidently. “Our rain stopper is the best in Lombok.”

On the evening of the party, a full moon had shone in a cloudless sky, although the very next morning it came pouring down. “What good luck we had last night with the rain,” a guest commented. The hotel manager only winked at me. An extra hundred dollars was discreetly added to our bill with “pawang hujan service” next to it.

-----

After that, I’d begun to notice references to pawang hujan everywhere. Wedding organisers advertised their services, but also golf courses and concert venues. Political parties used them during campaign season. City governments had them on their payrolls.

When a storage tank at an oil company facility caught fire, a pawang hujan was enlisted to help extinguish the flames. A 2014 article in the Jakarta Post detailed the debate raging in the city council of Surabaya, in east Java, over the budgetary inclusion of pawang hujan. The departments of education and youth and sports wanted a rain shaman budget, while other departments were of the opinion that they were “unscientific” and undeserving of public funds.

When I quizzed my Indonesian friends, they, almost without exception, recalled attending events where pawang hujan had exercised their powers. Trinity, a celebrity travel writer and a hard-drinking sceptic, looked solemn as she told me about her dealings with rain shaman. “I never believed in all this, but then I began working as an event manager at a golf course in Karawaci (a Jakarta suburb). I had to hire a pawang hujan before every tournament.”

Her eyes had widened as she’d described the shaman—who had been up all-night reciting Quranic verses in preparation—thrusting his arms slowly towards the sky as though pushing away a great weight, and how the dark rain-laden clouds obeyed. “I get goose bumps just talking about it,” she’d said.

A week later I went to visit Babey.

-----

The rain shaman’s real name was Mohammad Yusuf, Babey being an honorific like, “bapu” or “father”. His neighbourhood, Mampang, was only a 15-minute drive south from the house I used to live in, but it was a world away in other respects.

The zigzagging alleyways that lead to his rooms were too narrow for a car, so I’d had to walk the final few metres. There was no formal address. I’d asked a couple of headscarved ladies—hanging their laundry on lines fastened over the open sewers that line their shacks—for directions to Babey’s home. They’d only shaken their heads blankly.

Babey’s neighbourhood. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

Ice cream sellers and meatball-soup vendors walked the bylanes blasting recorded music from their trolleys. A clutch of chickens ran by my feet. Eventually an old man on a low stool amidst a heap of broken plastic toys had gestured towards the right. “Just keep that way,” he’d mumbled.

Moments later I was seated cross-legged on the floor of Babey’s front room, atop a plastic mat that featured the emblems of Manchester United and assorted other football teams. It was a confined space but managed to fit in a TV as well as a display case crammed with a cassette recorder, unspooling tapes, several bottles of medication, tissue boxes, cigarette packets and lighters, fading photographs of family members, and a Prabowo-Hatta campaign cap, a relic of the 2014 Presidential elections.

On one wall hung a somewhat lurid poster of the Wali Songo, or nine Muslim saints, who are believed to have spread Islam across Java over the 15th and 16th centuries. On another wall there were pictures of Babey on Haj, the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca.

Babey at home. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

The majority of pawang hujan, I discovered were hajis (people who had made the pilgrimage). The power to intervene in the rain was not an inherited trait but one that was acquired as a direct consequence of deep piety.

Babey was the only pawang hujan in his family that he knew of, although his mother - who’d taught Quran reading at the local school - had been widely believed to “punya ilmu” ie: with a feeling for the preternatural.

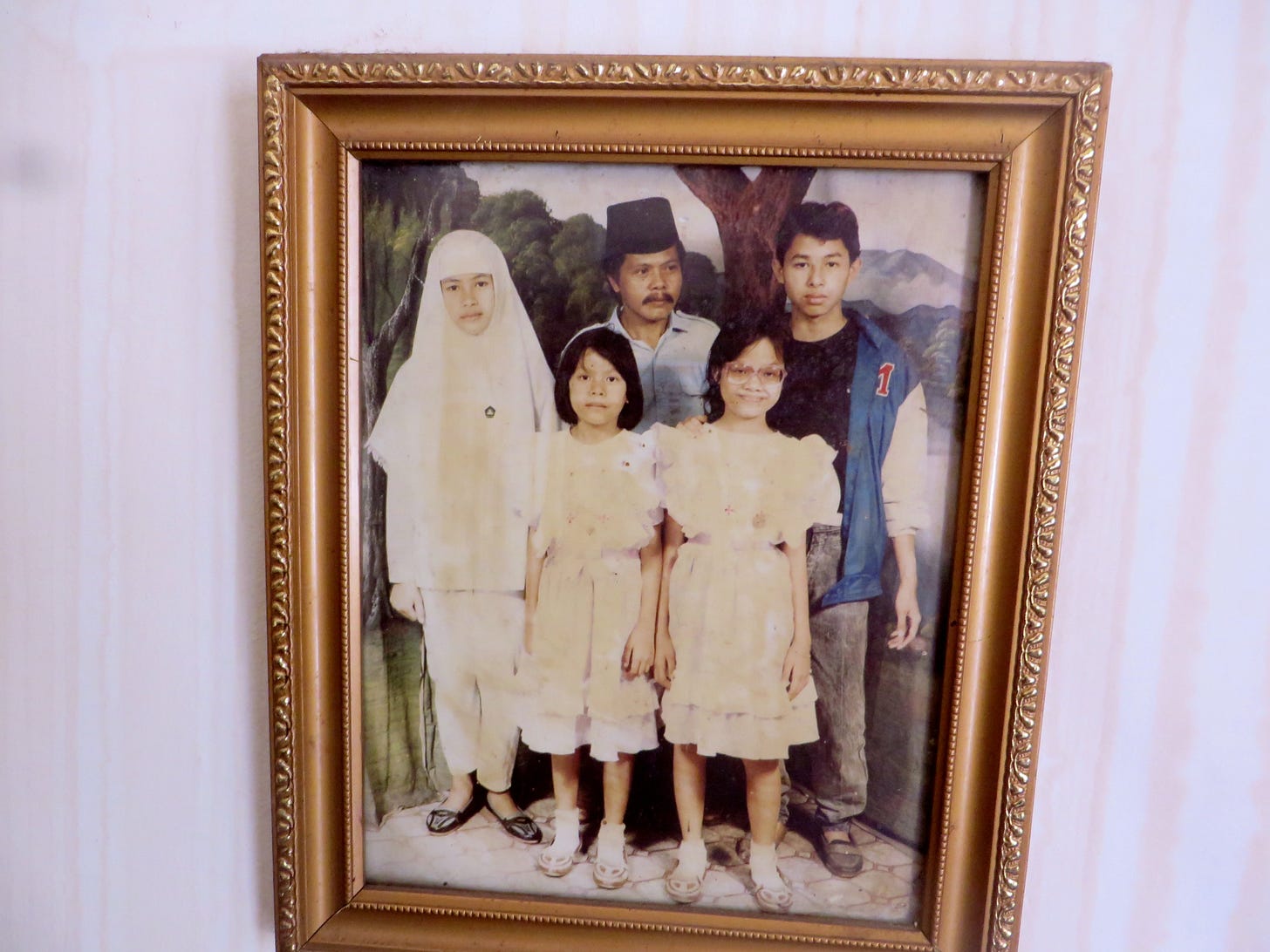

A younger Babey with his family. Pic: Pallavi Aiyar

Babey had been a pious child. His spirituality had caught the attention of an acquaintance who was constructing a toll road on the outskirts of Jakarta in the late 1970s. The contractor asked Babey to recite some prayers for the success of the project. From then on, the young man’s reputation as a shaman began to grow.

****

Babey was vague on the details of when and why he began to specialise in manipulating the rain. But he was very clear on one thing: pawang hujan do not have the power to stop the rain. Such power belongs only to Allah.

The shaman can, however, temporarily shift the rain to another place.

A problem occurs when two rival pawang hujan working for different clients in contiguous areas attempt to move the same rain. The only times he had not fully succeeded, Babey said, was when a competing rain shaman was working against him.

“There is a battle in the sky, the clouds moved this way and that.” But he hastened to add that he had never completely failed. Even when unable to shift the rain, he’d always managed to ensure that a downpour turned to a manageable drizzle.

Each pawang hujan has his own style. Many make offerings of cigarettes, rice, onions, spices and flowers. Others fast and meditate, relying solely on their internal strength. Babey’s method involved reciting specific verses from the Quran, including chanting the 99 names of God, and flinging about some salt. Table-variety sodium chloride bought from the local market, he confirmed.

Amongst his most loyal clients was a tobacco company. He recalled travelling across the Indonesian archipelago to ensure the company’s product launches were drizzle-free. Others include hotels, a funeral organiser, and even a Christian pastor who had wanted clear skies for a church event. “You see,” he explained, “my power is not about religion, but belief.”

----

Such distinctions were not mere sophistry. They were widely accepted as valid by most Indonesians. And they arguably enabled the Muslim-majority nation to retain a uniquely syncretic religious practice and outlook, despite attempts to standardise Islamic practice in keeping with Wahhabi norms.

There was, for example, a commonly made separation between agama or religion, and adat, or traditional cultural practices. Many Islamic organisations permited their members to participate in indigenous rituals and festivals that, while not strictly speaking Islamic, were part of adat or customary culture.

The notion that adat as culture was somehow divorced from agama as religion can seem to be a dubious one. But it allows Indonesians to negotiate their multiple identities without an overt sense of contradiction.

In the Indonesian acceptance of paradox, love of ritual, and tolerance of difference, I was powerfully reminded of the India I had grown up in. Given the plural complexities of the two nations, Indians and Indonesians had both had to hone the rare arts of getting along and leaving alone.

They may practice these arts imperfectly, but it was in this pursuit that the fragile essence of their nationhoods reside. It was the capacity to define oneself as this and that, rather than this not that. It was what allows a neuroscientist in Bangalore to mutter a morning prayer in her puja room before making her way to the research lab. It was why a Christian priest can call upon the mystical powers of a Muslim rain shaman in Jakarta.

-----

Back in Mampang, Babey had urged me to drink the sweet black tea his daughter had poured for us. He’d apologised for the humble repast. When younger he used to work as a security guard, but now his only income came from his services as a pawang hujan. These could pull in anything between 30-180 dollars per job. But assignments were unpredictable and limited to the rainy season. Outside the open door of Babey’s shack a vendor selling goldfish from a large plastic bag cycled by. The sky was white-hot and clear.

“It will rain soon,” the pawang hujan had smiled.

(A version of this story first appeared in The Indian Quarterly)

****

Please upgrade to a paid subscription, if possible. Its only the price of a coffee per month, and since you are what you read - that’s a pretty good investment :-)

You could also consider gifting a subscription to a friend for Christmas.

This is extremely interesting but has anyone tried to examine it from a scientific perspective? It would be useful to know.

Dear Pallavi, sorry to be shamelessly exploiting this comment for an unrelated, yet critical matter for India's international tourism.

My wife and I beat you to India by a couple of days; we have proved that in India nothing is impossible, but don't press your luck. The Sunday edition of the TIMES has an article on us as the first tourists in Kumarakom. We detail how the current Covid-tracking system, now extended to international tourists, makes it impossible to enter the country. Just a taste: how is an international tourist who is abroad to provide an *Indian mobile number*?

Please, use your connections and skills and enlighten the centre. Failing international tourists a few hours before boarding the plane is the sure and true way to destroy one's reputation as an international destination. India deserves better than this - and you can prove your mettle as a mediator.