Iron Moon: The poetry of China's Migrant Workers

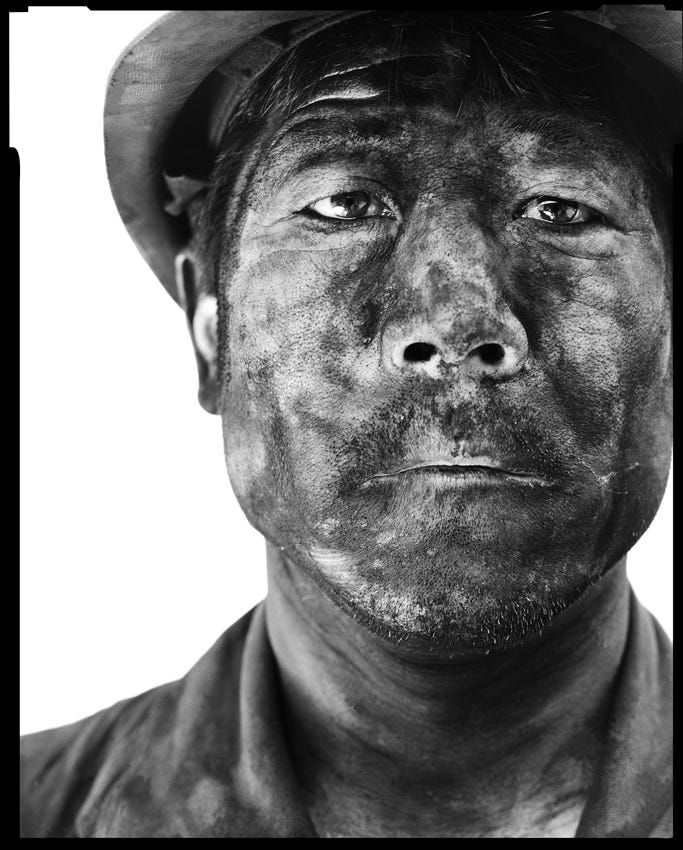

China’s 270-odd million migrant workers are the coal-blackened, chipped-tooth, often suicidal face of globalization.

Hola Global Jigsawers,

I am back in Madrid and at work, bringing you fresh writing that hopefully makes you think anew.

Today’s post is about China’s migrant worker poets. Please read and share.

*****

Foreigners are often taken aback on their first visits to China. Even second-tier cities that few outside of the mainland could place on a map, like Wuxi and Xiamen, dazzle with their infrastructural pyrotechnics. Butter smooth highways, multi-laned overpasses and chrome skyscrapers are the standard architectural backdrop to contemporary Chinese cities.

But what is obscured by these glitzy surfaces is the grimy reality that allowed them to come into being. The construction of contemporary China - and more generally its stunning ascent to global economic superpowerdom - was underpinned by a Soviet-style internal passport, called the hukou.

****

The Hukou

Designed in the 1960s during the Maoist heydays, the hukou system ensured that China’s urban centers were cocooned from the armies of peasants for whom the road to the city represented an opportunity to escape from grinding poverty. Under it, urban citizens were entitled to a range of social services including education, health care and social security, provided for by the urban authority under which they were registered.

But rural migrants who moved to the city had to in effect give up the rights to the protections that citizenship of a country usually confer.

Once China embraced the red capitalism that made it the factory of the world, it gradually loosened the restrictions on mobility. But it did so just enough to fulfill the requirement for the platoons of workers needed to work in the factories and warehouses that churned out the world’s iPhone and buttons, cigarette lighters and computer chips.

Even today, this labour force continues to be second class citizens within their own country. Despite hukou reform that has partially ameliorated the most egregious of the practical discriminations faced by internal immigrants, China’s 270-odd million migrant workers remain the coal-blackened, chipped-tooth, often suicidal face of globalization.

Chinese Coal-miner Credit: Song Chao

****

The poems

But what is often not known or understood outside China is the ability of ordinary people to fight for agency even in the most difficult of circumstances. And one example of this phenomenon is the remarkable flowering of migrant worker poetry over the last decade. These poems are typed into basic mobile phones and shared on online platforms until they are taken down by censors. But often, they find the wings to fly viral in the brief period before they are discovered and erased.

These are poems that find their vocabulary in the industrial. There is something metallic about them; something loud – like the roar of a furnace. Those who pen them are workers, as dispensable as surgical masks, and their poetry is shorn of any sentimentality, even as it sometimes coopts allusions to classical Chinese poetry with images like the moon.

The migrant worker poet as a character in China’s social landscape first came to prominence in the 2015 film, the Iron Moon. It followed several workers in construction, on the assembly line and in mines, who wrote poetry in what little spare time they had.

The most well-known of these poets is probably Xu Lizhi, a labourer who took his own life at the age of 24 in in the southern city of Shenzhen. Xu worked for the Taiwanese company Foxconn, that is known for manufacturing video game consoles and Apple products. In 2010, Foxconn made international news when reports surfaced of a spree of worker suicides in response to the harsh working conditions they faced. Notoriously the company’s response was to set up safety nets under its windows to prevent more employees from leaping off their buildings.

Xu Lizhi avoided the nets and leapt to his death in September 2014 from the roof a shopping mall which housed his favoutite bookshop. His legacy has been substantial, as his poems were widely read and shared across the internet, posthumously making him into a celebrated poet

Here is one of his poems from which the movie, Iron Moon, took its name:

I swallowed an iron moon

they called it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labour, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow any more

everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country

a poem of shame

(Translated by Eleanor Goodman)

And here’s another:

A Screw Fell to the Ground (January 9, 2014)

A screw fell to the ground

In this dark night of overtime

Plunging vertically, lightly clinking

It won’t attract anyone’s attention

Just like last time

On a night like this

When someone plunged to the ground

******

This next poem is by Chen Nianxi, a miner who spent 15 years laboring in gold, iron and zinc mines across China. He’s made it to the big league, so much so that The New York times recently did a profile on him.

The following poem was written for his son who, unlike Chen himself, has a college education.

Your clear eyes

Penetrate text and numbers …

But still cannot see the real scenes of this world

I want you to bypass your books and see this world

But also fear that you would really see it

*****

A final example. This one is by Zheng Xiaoqiong, who worked for years in a die-mold factory and as hole-punch operator. She calls her sensibility the “aesthetic of iron.”

These are the opening lines of a poem called Language:

I speak this sharp-edged, oiled language

Of cast iron - the language of silent workers

A language of tightening crimping and memories of iron sheets

A language like callouses fierce crying unlucky

Hurting hungry language back pay of the machine’s roar occupational diseases language of severed fingers

(Note: All these poems are taken from the anthology, Iron Moon, named after the movie. They are into English by Eleanor Goodman)

***

The challenge to the CPC

The significance of these poets goes beyond being mere curiosities or objects of pathos Cooption has been a key part of the Communist Party of China’s strategy for continued leadership. Ironically, this party that formerly represented the workers and peasants, has mostly come to represent the urban middle-classes, the bourgeoisie.

The CPC’s ability to co-opt or otherwise pacify migrant workers will be the litmus test for its ability to continue in power long-term. From the outside, Chinese politics appears opaque and untrammeled by domestic resistance. In reality, the leadership has to walk a tightrope between dangling carrots and wielding sticks while trying to “harmonize” the very divergent interests of all its different constituencies.

The migrant worker poet is a force to watch out for.

******

Indian contrast

As a quick conclusion, I’ve been struck by the lack of similar agency and self-representation by India’s migrant workers. These comprise some 20 percent of India’s work force and their plight was brought into sharp relief by the Covid lockdown imposed in early 2020.

The front pages of Indian newspapers suddenly awoke to their plight. For a few weeks we were shown daily images of tens of thousands of labourers walking on foot in the scorching heat of summer to reach their home villages.

And yet the only poem I could find in the media about them came not from amongst them, but from India’s most over-exposed celebrity Bollywood lyricist, Gulzar.

Why do you think this to be the case? Where are India’s migrant worker poets?

I would love to have your feedback and comments. And do consider subscribing to the Global Jigsaw to support my writing.

Until next week.

xo

P