Hola Global Jigsaw,

As promised, I’m continuing with reviews of two more books that I read last year. This time what connects them is the country that I began my career as a foreign correspondent in: China.

When I moved to Beijing in 2002, the only constant was change. The capital city was shrouded in construction dust, as it was razed to the ground and built anew with a speed that saw the municipality issuing new maps every few months.

I remember watching a group of elderly, pepper pot-haired women performing a fan dance routine in front of a gigantic pile of rubble – the remnants of their recently demised housing block. I wondered then, how the older generation in China kept their sense of self intact, given the repeated epochal transformations they had experienced within their lifetime.

One of the neighbours in the central Beijing alleyway that I lived in, was a 90 year old lady, called Lao Tai Tai or “Old Mrs.” Her face was laced with a maze of fine lines, but it was her miniature feet that drew attention. Starting from the age of six, the bones in her feet had repeatedly been broken and bent to achieve impossibly tiny (and deformed) “lotus feet.” Having bound feet was once the standard of beauty in China, akin to the modern day Brazilian butt lift in the Kim Kardashian/Instagram-inspired universe. Foot binding was banned in 1912 (although only really stamped out after the communist accession in 1949).

Lao Tai Tai told me she had moved to Beijing from a village in Shandong province in 1946. I remember being gobsmacked at the thought of how in her own lifetime she had seen imperial China morph into a communist country and then witnessed the capricious horrors of Mao’s mass campaigns give way to the capitalist excesses of the twenty-first century. How did she process all of this? How did she maintain a personal narrative arc that was not as violently fractured as the broader political canvas against which her life had played out? How did China, more broadly, retain its core identity, in the shifting sands of its politics?

Over time I concluded that the two sources of continuity in China were its unique and ancient written language and food. It was these two elements, more than religion or architecture or climate, that stitched a unifying tapestry out of the diversity of this empire-like country.

All of which is by way of introduction to the two books. One has to do with script and the other with gastronomy. The first, Kingdom of Characters, by Jing Tsu, is about the written Chinese language and the challenges posed to it by modern technology. The second, Invitation to a Banquet, is by my favorite writer on China’s culinary history and topography, Fuchsia Dunlop.

xxx

Available here

Almost no “historical” building in China has survived very long – these are in a constant state of being rebuilt – the result of fires, wars, natural disasters, and “upgradation.” But Jing Tsu, a professor of Chinese literature and culture at Yale university, points out that the written form of Chinese has remained largely unchanged for 2200 years. (By comparison, the number of letters in the Roman alphabet remained in flux until the 16th century, when ‘j’ split from ‘i’ and completed the 26 letter English alphabet in current use.)

There is something sacred about the written word in China, underscored by the reverence accorded to calligraphy even today – when the art of handwriting is increasingly becoming archaic the world over. Mao’s calligraphy, for example, is still featured on the masthead of the People’s Daily newspaper. It is telling that calligraphy survived as a practice under the communists, even as they sought to destroy other elite cultural markers from religion to literature.

The Kingdom of Characters brings together the stories of a smorgasbord of Chinese intellectuals, diplomats, librarians and teachers in their attempt to make the written Chinese language compatible with modern technologies like the telegraph, typewriter and computer.

Chinese is a non-alphabetic language. It uses characters - written units made up of strokes, that combine indications of meaning and sound. There are more than 100,000 different Chinese characters, (no precise number is available). The number of useful characters, for a literate person however, is “only” between 3,000 and 6,000.

The central problem of Chinese characters and modern communications technology has been the problem of the keyboard, the device that enables language to be inputted into a system that then enables it to be disseminated over distance. Keyboards were devised with the Roman phonetic alphabetic universe in mind, rather than characters.

Trying to devise portable machines, like the typewriter, that could type 4,000 individual characters was thus a monumental, at times seemingly Sisyphean, task. So much so that political debates raged in 19th and 20th century China, between those who saw characters as inherently incompatible with modernity or logical, abstract thinking, and those who sought to retain the script even as they ran up against western-developed tech’s inability to accommodate it.

xxxx

A fascinating chapter in the Kingdom of Characters is on the decision made by the communists to simplify the language in order to stamp out illiteracy. This was done in a two-pronged manner. Firstly, the number of strokes that comprises each character was reduced, making it easier to remember.

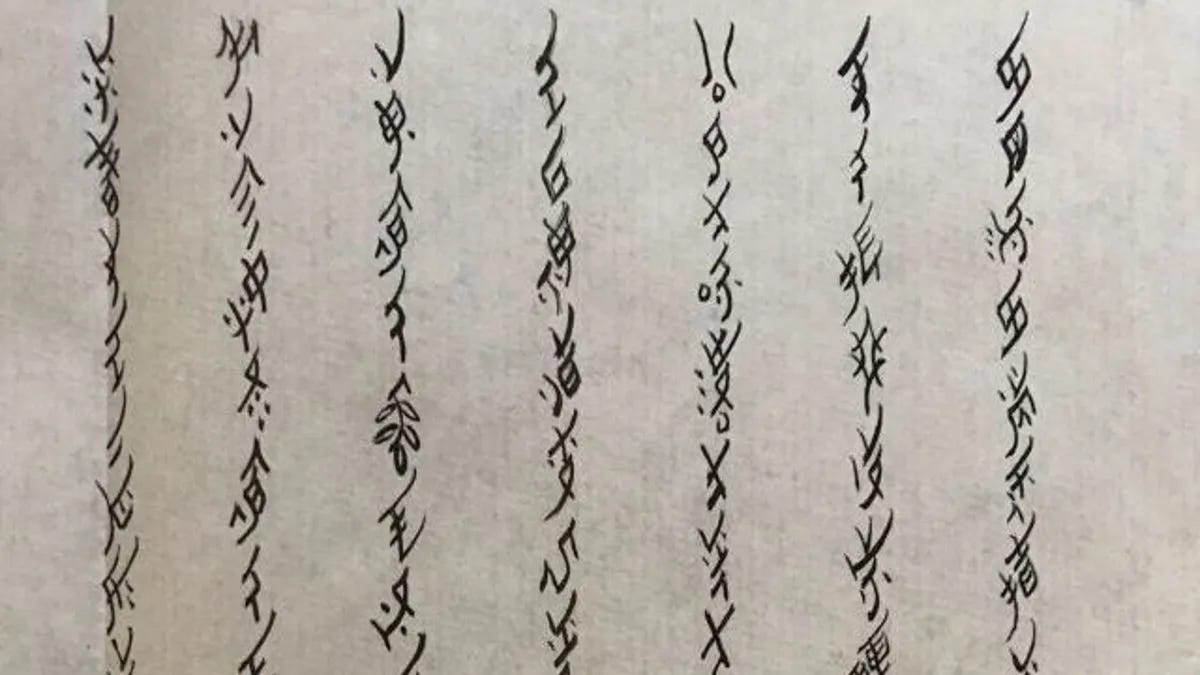

Simplified Chinese in fact had precedents in, for example, a script called Nüshu or “women’s script,” - a truly fascinating subject of its own and one that Tsu addresses only in passing. Nüshu was a pared down way of writing, devised originally by women in the country’s south-eastern province of Hunan, as a secret script to communicate between themselves. This unspoken, purely written language, took its inspiration from embroidery, incorporating stitch-like crisscross patterns.

Succor-giving words of friendship and comfort were embroidered in Nüshu on handkerchiefs, headscarves, fans or cotton belts and exchanged. It was used by women in this part of China for centuries, enabling them to gain literacy even when formal education was denied to them. And to have private, in-group, communications outside of the patriarchal system.

The female-only Nüshu script from China’s Hunan province. Image: Ilaria Maria Sala

Returning to the communists, in addition to character simplification, a campaign to develop a standardised system to write Chinese using the Roman alphabet was also launched under Mao. Attempts to do so had been ongoing ever since foreigners had contact with China, but these had been erratic. It was only in the second half of the 20th century that a Romanization system called Pinyin was officially adopted.

The path to this decision was a hotly contested one. While some argued in favour of abolishing characters all together, the idea of Romanization was also fiercely opposed for a variety reasons. Some of these were emotional, but there were also some intractably practical problems with converting characters into a phonetic alphabet.

In particular, there was the thorny issue of homophones and tones.

An inordinate number of Chinese characters are represented by the same sound – leading to the same spelling in alphabetic form. The Romanized spelling of “yi” for instance is shared by nearly 200 characters, which Tsu points out could mean ‘one,’ ‘cloth,’ ‘to lean,’ ‘she,’ ‘ripple,’ ‘a squeal’ and so on. Secondly, characters with the same alphabetic spelling also have different tones which completely alter the meaning. The Pinyin word “ma” for example can mean ‘horse,’ ‘mother,’ ‘hemp,’ or ‘to scold,’ depending on the tone that is built into the pronunciation.

Tsu recalls the story of Zhao Yuanren, a celebrated Chinese linguist, who set out to demonstrate that tones were the most meaningful element of a character and were totally unable to be expressed adequately in Pinyin. To do so, he composed a 92-character story using 31 different characters about a man called Shi who mistakenly tried to eat ten lions carved from stone.

This is how it read in Chinese:

石室诗士施氏,嗜狮,誓食十狮。

氏时时适市视狮。

十时,适十狮适市。

是时,适施氏适市。

氏视是十狮,恃矢势,使是十狮逝世。

氏拾是十狮尸,适石室。

石室湿,氏使侍拭石室。

石室拭,氏始试食是十狮。

食时,始识是十狮尸,实十石狮尸。

试释是事。

But this is how it would be Romanized in Pinyin:

Shī Shì shí shī shǐ

Shíshì shīshì Shī Shì, shì shī, shì shí shí shī.

Shì shíshí shì shì shì shī.

Shí shí, shì shí shī shì shì.

Shì shí, shì Shī Shì shì shì.

Shì shì shì shí shī, shì shǐ shì, shǐ shì shí shī shìshì.

Shì shí shì shí shī shī, shì shíshì.

Shíshì shī, Shì shǐ shì shì shíshì.

Shíshì shì, Shì shǐ shì shí shì shí shī.

Shí shí, shǐ shí shì shí shī shī, shí shí shí shī shī.

Shì shì shì shì.

Here’s an English translation:

The Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den

In a stone den was a poet called Shi Shi, who was a lion addict and had resolved to eat ten lions.

He often went to the market to look for lions.

At ten o’clock, ten lions had just arrived at the market.

At that time, Shi had just arrived at the market.

He saw those ten lions and, using his trusty arrows, caused the ten lions to die.

He brought the corpses of the ten lions to the stone den.

The stone den was damp. So he asked his servants to wipe it.

After wiping the stone den, he tried to eat those ten lions.

When he ate, he realized that these ten lions were, in fact, ten stone lion corpses.

Try to explain this matter.

xxxx

This example makes clear the limitations of Pinyin as a replacement for characters. However, its adoption as an addition to characters did prove useful. Nationwide instruction in Pinyin was launched in the fall of 1958 and according to Tsu, 50 million people learned it within the first year. Pinyin was to go on to become the medium via which China engaged the world and modern technology. (I myself first learned Chinese in Pinyin and only after having become capable of everyday conversations did I attempt to learn characters.)

To use a computer keyboard today, you must first type in the Pinyin for a character. You are then offered a range of characters (all homonyms in Pinyin) matching the spelling of the word you have inputted, between which to choose the one you in fact want. Its less complicated than it sounds once you get used to it.

The fact that everyone who has gone through the educational system in China has a familiarity with the Roman alphabet allows the Chinese to engage globally with more ease than would otherwise have been the case.

xxx

I realise that I am still to review Dunlop’s book on Chinese food, which given the length of this newsletter will have to wait till next week.

I hope you enjoyed this post and will share it. Please let me know your thoughts. I love hearing from you. And do become a paid subscriber to support my work – you can be modern day Medicis :-)

Hasta pronto,

Pallavi