Hola Global Jigsaw,

Tis the season. In Madrid, the evenings are glowing with Christmas lights. Artisanal markets have sprung up across the city and the scent of hot chocolate is pervasive. In Spain, nativity scenes, also known as belen (the Spanish word for Bethlehem), are a major feature of traditional festivities. These are like dioramas depicting the birth of Christ, similar to the jhankis that we in India put up on Janmashtmi (the birth of Krishna).

A belen in central Madrid

But for today’s post, I thought I’d take you to somewhere rarely associated with Christmas: China - this, despite the fact that for most of the 21st century, Christmas has literally been “Made in China.” Ninety percent of global Christmas decorations, and almost all artificial Christmas trees, are manufactured in the erstwhile Middle Kingdom.

When I lived in Beijing (2002-2009), I had the opportunity to witness first-hand, the Chinese going Christmas-mad. Here are some recollections. But first, could I ask you to buy a Global Jigsaw subscription as a Christmas gift for a friend? Or for yourself, if you haven’t already? You can read most of my writings for free, but that doesn’t mean they are free.

Thanks much :-)

xxxx

It was a freezing Christmas eve in 2007. As the clock slowly ticked closer to midnigh, the whipping wind lashed the faces of those who had been lining up for hours. Occasionally, a whispered conversation would lead to a furtive exchange in the shadows: cash in return for an entry pass that secured admission to the imposing, century-old building. Giant flat screen LCD displays flashed across the facade, providing a view for the hundreds who had been able to gain entrance into the grounds, but still remained unable to actually push their way inside.

Finally, twelve gongs rang out into the night, heralding the anticipated hour and the thousands gathered outside, burst into song. The words were in Chinese, but the tune was universally recognizable. “Silent night, Holy night,” people sang in harmony, and thus began the midnight mass at Beijing’s Xuanwumen Church, the oldest Catholic church in the Chinese capital.

Only a decade earlier, all public celebrations of Christmas in China had been banned. Since the country’s Communist Revolution in 1949, the festival had been deemed a vehicle for insidious ideological pollution. But by the time I’d moved to Beijing in 2002, the authorities had changed tack. Instead of curtailing celebrations, they had actively begun to encourage them. This change of heart had less to do with any new found spiritual bent within the Party, which remained officially atheist, and more with a general encouragement of all opportunities to generate consumer spending.

As a result, in the run up to Christmas, all of Beijing’s major hotels, restaurants and shop fronts were decked out in wreaths and fairy lights. At the Laitai flower market, east of the Forbidden City, Chinese shoppers browsed among the shimmering trees, reindeer and Father Christmas figures in search of extra glitter for their homes. Although there were no overtly religious displays such as nativity scenes, normally surly sales staff dressed up in seasonal red and white, and pop versions of traditional carols played on a loop in the background.

KFC, the fast food chicken outlet, stands out as an example of China’s commercial Christmas. The brand has nailed the tactic of inventing Christmassy rituals that have nothing to do with the birth of Christ, but rather with the spending of money. This trend is most famous in Japan, but has begun catching on in China too.

In 2019, KFC China invited a group of officially trained Finnish “Santa Clauses” to travel to six cities in China, tasting KFC “Christmas breakfast” items and going sightseeing, gaining much attention and popularity on social media. For many youngsters, going to KFC is now a Christmas ritual.

In Beijing, Yu Yang, one of my students from the Beijing Broadcasting Institute where I used to teach, had told me that although she’d celebrated Christmas several times – it was only once she was in university that she’d discovered that the festival had anything at all to do with religion.

“It was quite a shock when an American friend told me she was going to go to Church on Christmas,” she’d said. “I asked her why on earth she would do something so boring when it was Christmas- a time to party!”

Of the several thousands of people gathered on Christmas Eve at Xuanwumen Church in 2007 for example, the majority were in their early twenties. Giggly, gangly couples hung on to each other’s arms as they queued up, reminiscent of lines for rock concerts. The entry passes that were clandestinely obtained by the entrepreneurial for cash, were in fact a tactic devised by the church to ensure that regular parishioners, numbering around 3,000, were able to gain access on the night, while the novelty seekers were kept at bay.

But it proved impossible to keep away the hordes of curious onlookers and the church was overflowing with over 5,000 people. Just before the mass began, a few minutes before midnight, a shout went up and the crowds within the church began to go wild. Finger tips waved in the air, girls tried to jump onto their boyfriends’ shoulders to get a better view.

Outside, the flat screen LCD displays revealed the cause of the excitement. Santa Claus had arrived and was throwing sweets into the congregation much like a rock star might dispense personal items to feverish fans.

A group of twenty odd elderly ladies, lips pursed, looked on disapprovingly. They were devout Christians they’d told me, and attended weekend masses regularly. “What do these people here know about God?” one of them had asked disparagingly.

xxxx

In China, proselytizing and weekday masses remain outlawed. Nonetheless, about 2% of Chinese adults or about 20 million people, openly self-identify as Christians.

Non-official estimates that include “home churches” or churches which are unregistered with the authorities, put the figure considerably higher, at around 80-100 million.

Since the ascent of Xi Jinping to China’s helm, the growth of Christianity in China appears to have stopped. The party is acutely aware of the role that Christians have played in anti-Communist movements in other countries. In 2018 and 2019 the government published five-year plans for sinifying each of the country’s five officially recognized faiths: Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and Christianity, which China treats as two separate religions: Protestantism and Catholicism.

Churches are now “encouraged” to use Chinese architecture and Chinese tunes for hymns, as well as Chinese-style painting, calligraphy and other “popular cultural forms”. More worryingly, from a freedom of faith perspective, churches must now adhere to the 2018 document on “revised regulations on religion.” This imposes tougher fines on the unauthorised use of premises for religious purposes and requires official permission for religious training abroad. Moreover, it urges preachers to promote “core socialist values” in their sermons.

****

This Christmas, it’s not only China’s Christians that will have cause to celebrate, but also tens of thousands of migrant labourers who work in the factories of the country’s southern boom towns.

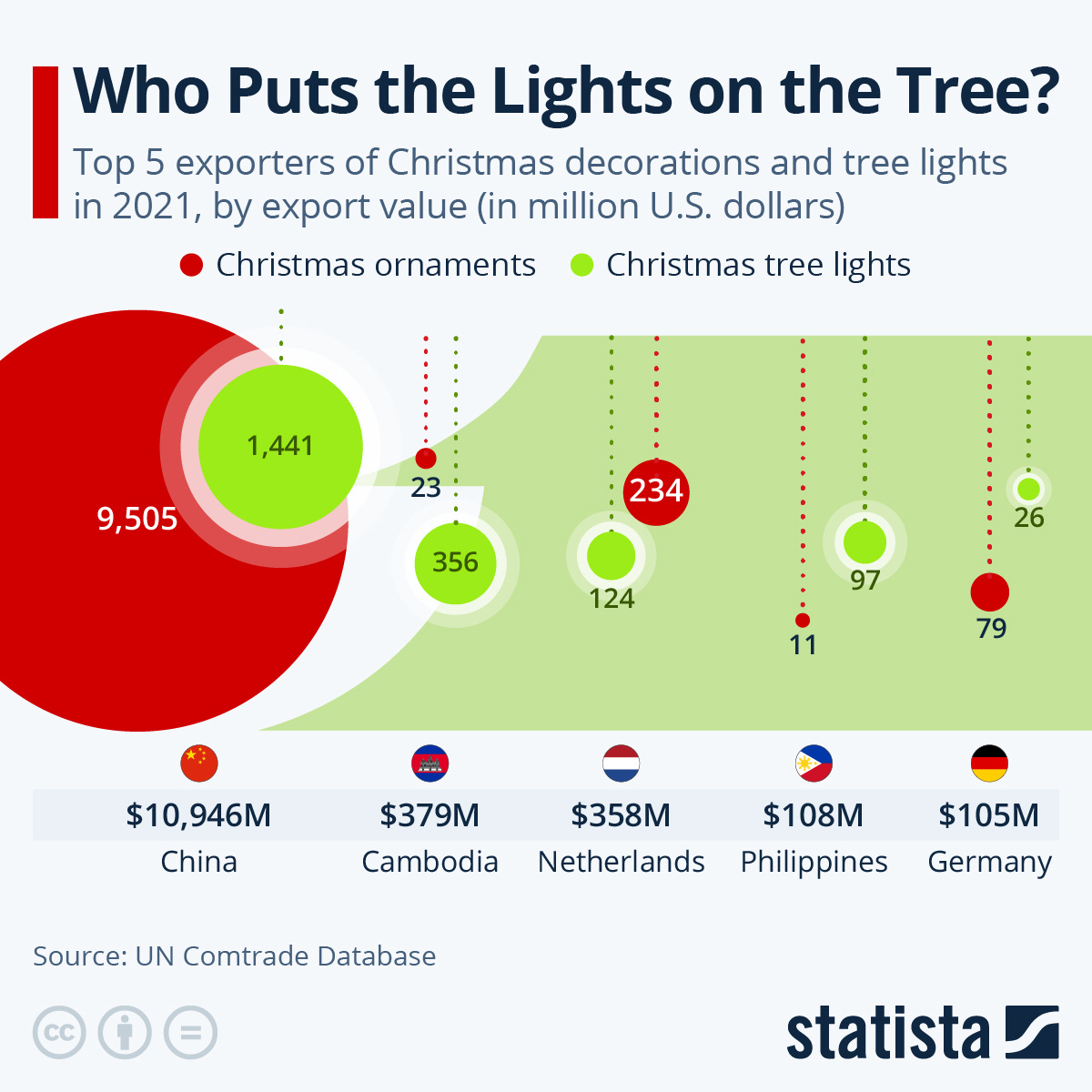

According to UN data, China accounts for 66 percent of global exports of Christmas tree lighting sets and 90 percent of exports of other Christmas decorations excluding candles and natural trees.

Over the last two decades, several small towns in Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces have gone from rags to riches all thanks to the Lord. For example, according to Xinhua news agency, more than 7000 farmers living in Xiaoguanzhuang town in Jiangsu province collectively manufactured some 100 million Christmas decorations for exports in 2004, earning close to $48.3 million. The town now has 45 large businesses and more than 400 processing workshops, producing angels, trees and reindeer.

A world away from the hipsters of China’s big cities, these peasant-workers know next to nothing about the festival for which they spend their hours and days labouring. Nonetheless it is they who often have the merriest Christmas of all.

Xxxxx

Hope you enjoyed this post, and also, that you have a very merry Christmas. The Global Jigsaw will be back in 2024. Please let me know if you have any knowledge of where time goes? I was only just becoming comfortable with it being 2023!

Anyway, cheers for the holidays.

xoxo

Pallavi

Wonderfully interesting, dear Pallavi - I have forwarded it to a dozen family and friends.

Happy Christmas in Spain! Hugs - Rolf

Very interesting. Too bad India missed the boat here on the commercial opportunity for exports. But in today's climate it would likely be a target for the puritans.

Feliz Navidad y Feliz ano nuevo!