Dear Global Jigsaw,

Once there was a magic Jar of Happiness. Every evening of last November, it would fill up with notes written in my mother’s pearly handwriting - a balm for my mutilated body. The love bursting from these notes was more powerful than any anti-inflammatory painkiller. It was a love 46-years in the making, as stubborn as only a mother’s can be - refusing to be dented by time or denuded by teenage rebellion or lessened by distance. It was lioness love. Broken-ankle-be-damned-love.

I was diagnosed with stage-II breast cancer in September 2022. A mastectomy and lymphodectomy were scheduled for a few weeks later. The surgery was to take place in Spain, where I lived with my husband and children. My mother was immediately on a flight from India to be with me.

She arrived in Madrid airport a few days before my surgery, in a wheelchair. She’d broken her ankle the day before she was scheduled to fly and had omitted telling me about the fall that caused the fracture. She hadn’t wanted me to dissuade her from coming.

When I first saw her hobbled and fragile, I’d felt a flash of irritation at her “irrationality.” Why had she come in this state? How was she going to look after me? We would now have two patients at home: my mother and I. And even at the best of times, Muma was infant-like when outside of her India comfort zone. She was baffled by microwaves and felled by WiFi passwords.

My surgery took place two days after she arrived. Luckily my boys, 11 and 14 at the time, were there to take care of their grandmother, while my husband stayed with me at the hospital. They operated the microwave and inputted passwords into her mobile phone. It is one of life’s great gifts for a grandchild to be able to “mother” a grandparent. They will never have that opportunity again.

Six months after her return to India, my mother died. Without warning. Without trouble. She’d spoken to me the evening before, and we’d made plans for meeting up this August to celebrate the end of a year of cancer-treatment for me. The next morning, she was “gone”. From one moment to the next, those words - “she’s gone” - cut me adrift, with no North Star with which to orient myself.

My mother, Gitanjali Aiyar, dancing up a storm

At the memorial service held in Delhi a few days later my brother paraphrased Auden in his eulogy.

“She was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,”

And so, it had been for me. She was my history and my memory. The reason why I liked the cushions on the sofa angled just so. Why I never pinned my saree pallus to the blouse. Why I sang the tunes I did to my boys at bedtime.

Grief, I’ve discovered, is a gravity-free zone: a floating dead weight. It is an un-filled zone, of becoming untethered, undone, unraveled. It is as insistent as a shadow, and like a shadow it lengthens and shortens through the day, but remains attached to your heels even as you might try and kick it off.

***

When I was diagnosed with cancer, I’d experienced shock akin to being plunged under icy water. And post-mastectomy there was a period of mourning the loss of my breast. It had been, as I wrote in another post, a good breast and it was painful to have it cut away literally and otherwise.

My mother, with her broken ankle, was a complicating and complicated presence. I wanted her, quite irrationality, to kiss and make it all better, which she couldn’t, for even mothers cannot banish cancer. She was also in pain herself, and frail, her stomach acting up, which made me guilty for not being well enough to look after her. Mothers and daughters and our tangle of love and guilt - it never ends.

What she did do was to tell me to rest, when everyone else was telling me to exercise. She massaged my shoulders gently; she stroked my hair. These were primal moments. They made me whole for a few seconds, recalling a time when I didn’t know what a surgery was, and everything was still ahead, and being brave meant holding back the tears because you came second in the three-legged race that you really, really wanted to win.

She got the idea for the “Jar of Happiness” from a prosaic book on the technical/practical aspects of breast cancer – The Complete Guide to Breast Cancer by Professor Trisha Greenhalgh and Dr Liz O’Riordan- that I had bought to help me learn about things like the Nottingham Prognostic Index and HER2 receptor status. Not your standard bed side reading, but my mother took it for hers. And amidst all the oncological acronyms, she found a section on tips to get through the early days of a diagnosis that included a suggestion to start a “jar of joy.”

The idea was for the cancer patient to write notes to herself every time she experienced a micro-joy - birds singing in the morning or a particularly tight hug from a child – and to put these in a jar. These could then be returned to when the patient felt low – guaranteed to put a smile on even the most chemo-fatigued face.

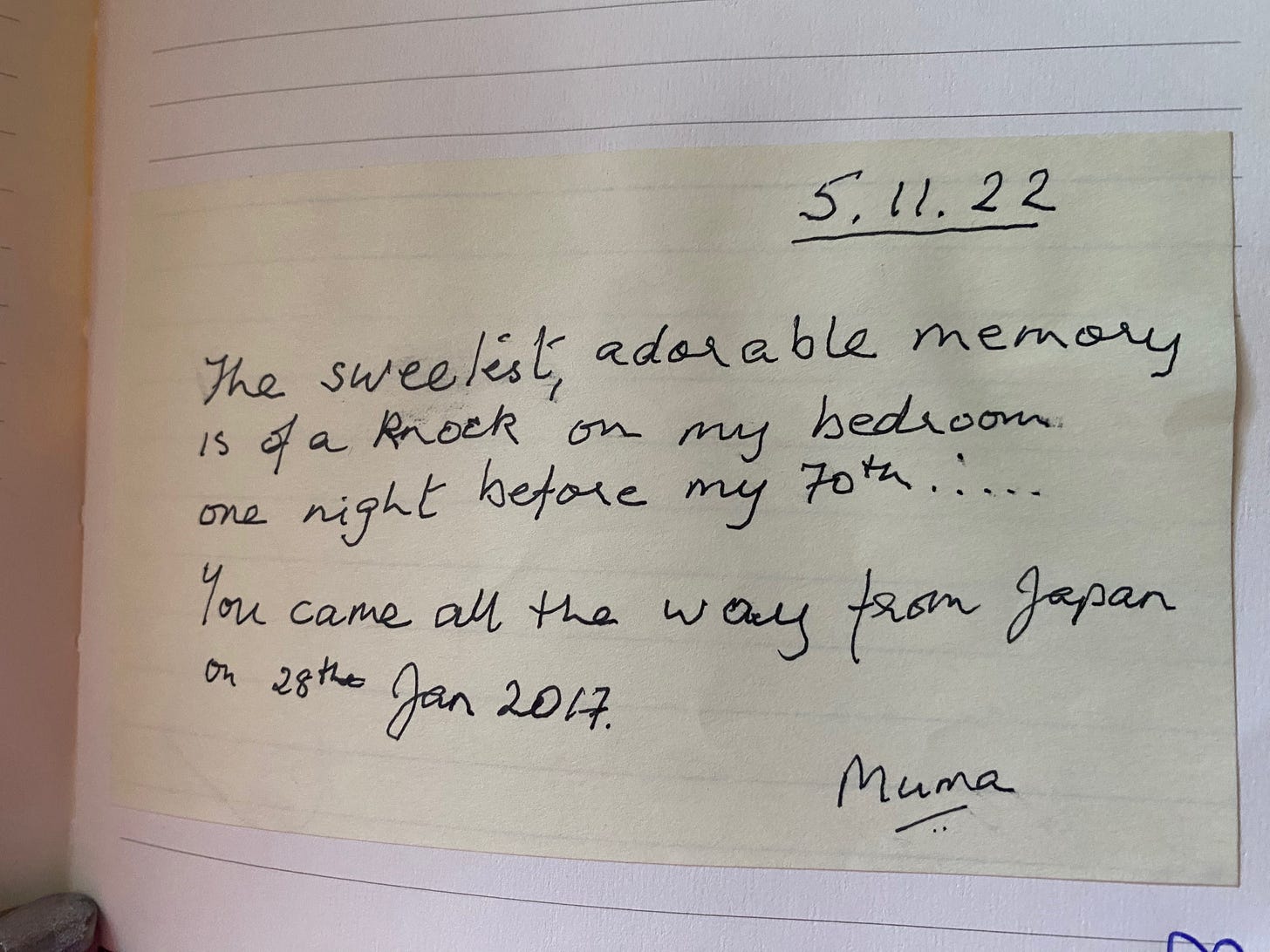

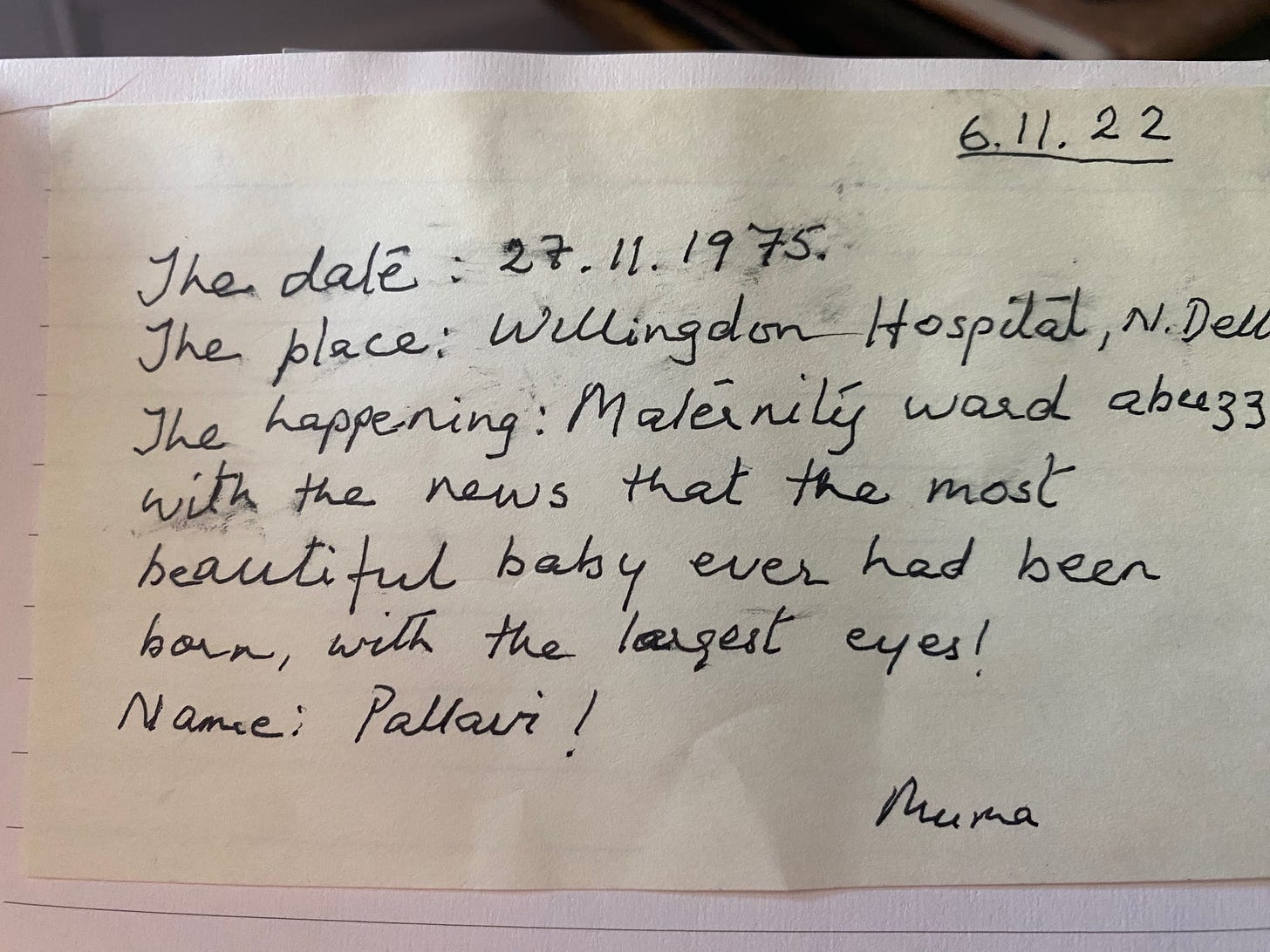

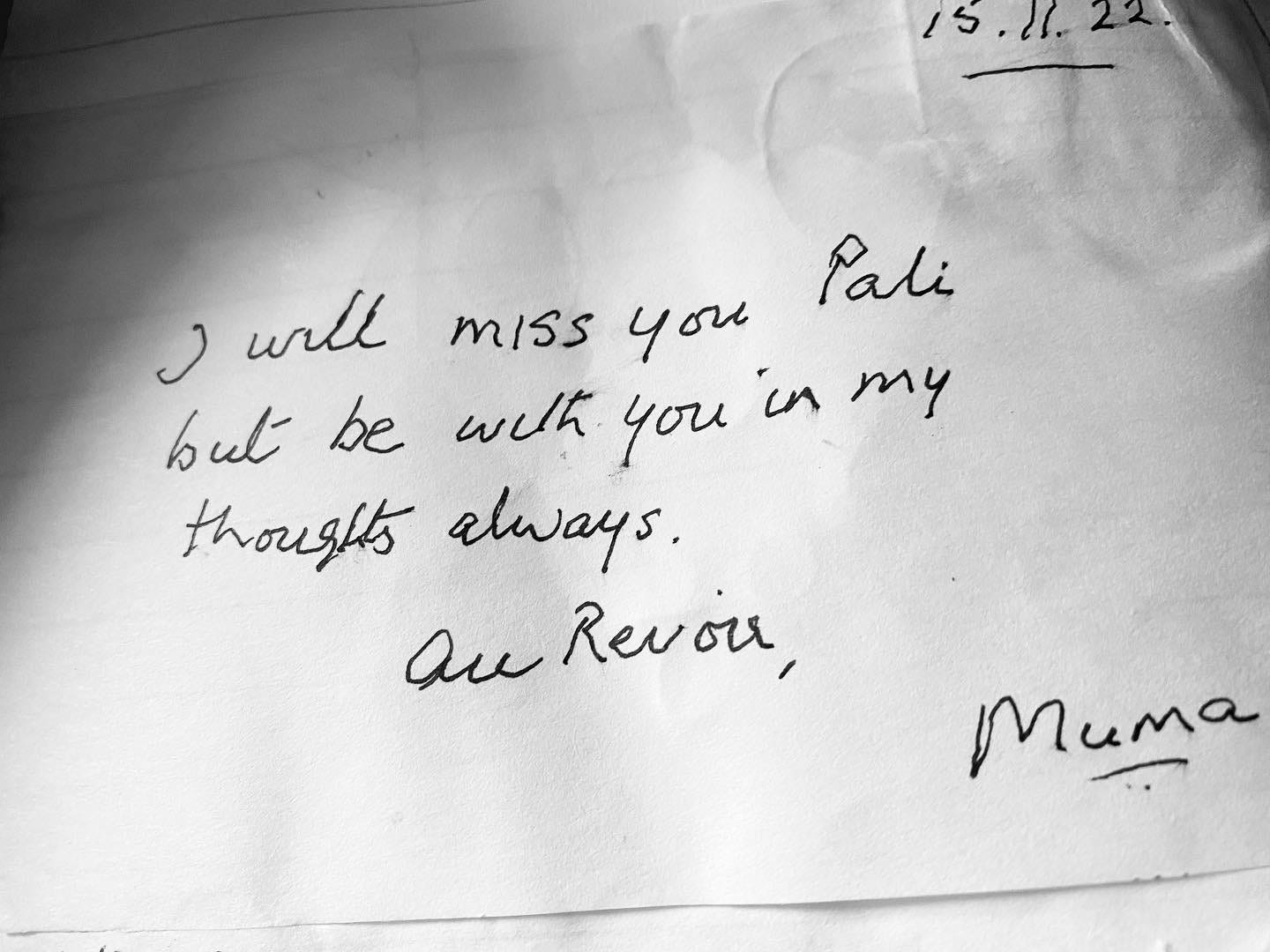

My mother’s version of this jar was to write notes to me. And so it is that I have 15 notes left to return to in my lowest moments after her passing. They were written by her when I last saw her alive, the last I will ever see her alive.

Here is a sampling:

11:11:22

Today you told me you get e everything I want. Truth is I got everything I want the day you were born.

Muma

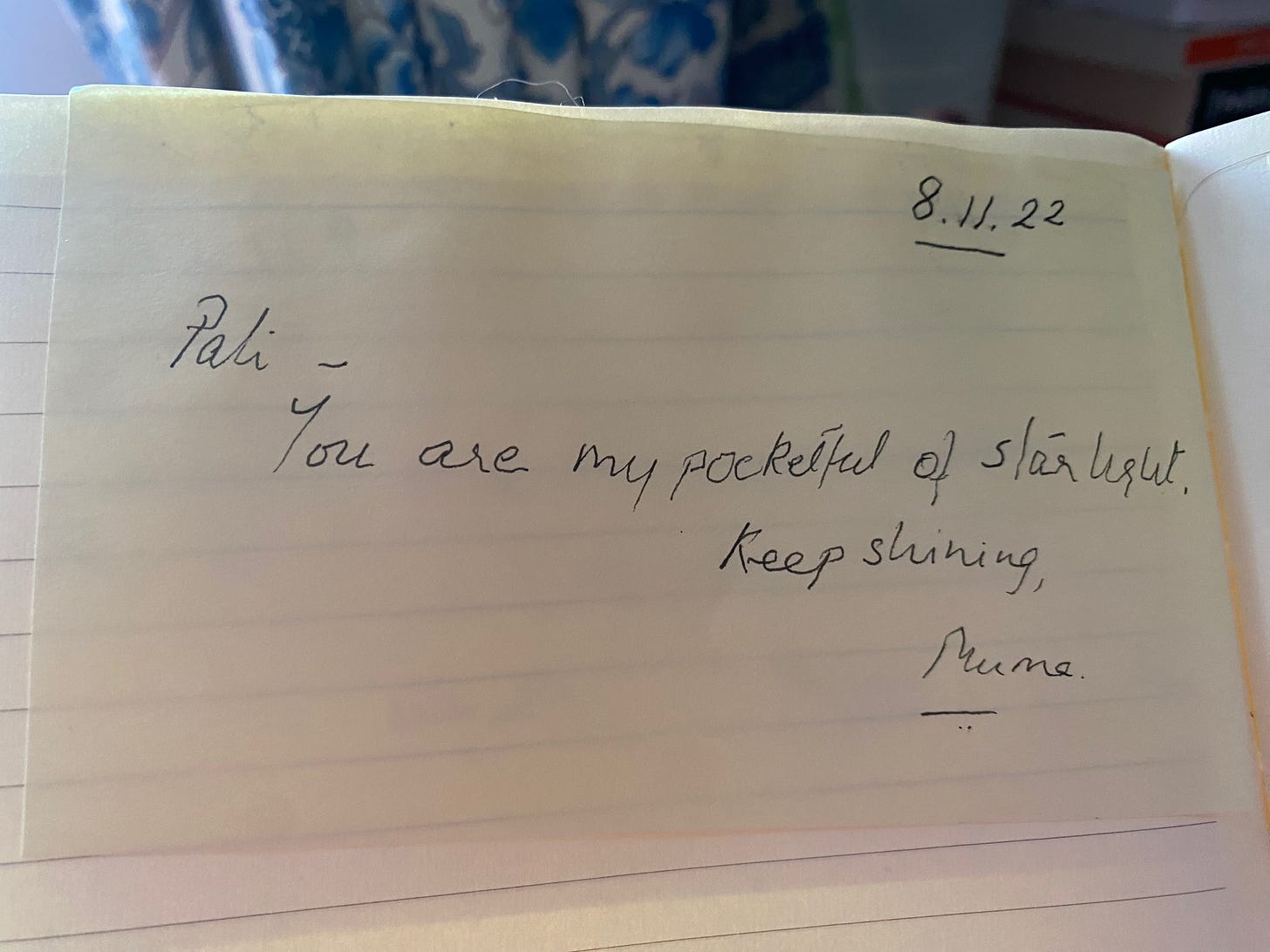

8.11.22

You are my pocketful of starlight. Keep shining,

Muma

3.11.22

When I’m with you it’s like “strawberries, cherries and the angels kissing spring.” I love you, Muma

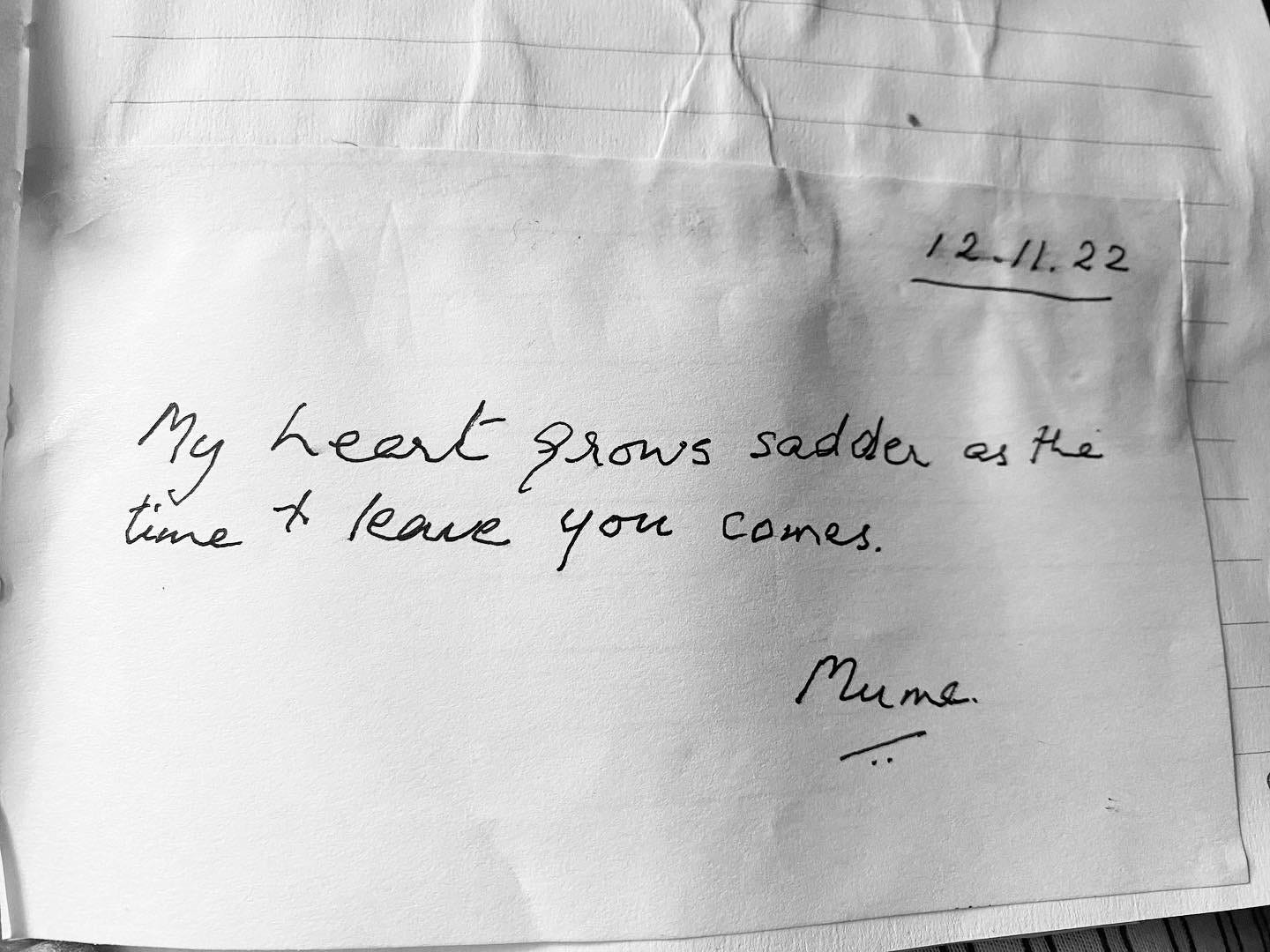

12.11.22

My heart grows sadder as the time to leave you comes.

Muma

I am not a mystically oriented person. But the hair stood up on my neck when I returned to Spain from my mother’s funeral in Delhi, and frantically pounced upon these notes, written six months before her passing. And I have been reading them again and again, for its like she’s telling me exactly what I need to hear. She is essentially kissing and making it better even though “she’s gone.”

Last night, I was crying softly in bed when my twelve-year-old, got in next to me and held me in his still-tiny arms. “You know what, Muma?” he said in a scientifically minded voice. “When a star dies, it becomes a red giant and then a nebula and then a white dwarf. And then some white dwarves have a helium flash, and they are born as stars again.”

The words hung between us. My future astrophysicist is sensitive enough not to belabor a point. As for me, I will be looking up at the night skies.

*****

Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to the Global Jigsaw. To do so, click here:

Until soon,

Pallavi

Pallavi this is your most moving and beautiful article…It made me feel that somehow your Mum is alive in you. She will keep lighting up your days and help you overcome your sadness

Beautiful. As was your Mom.