Hola Global Jigsaw,

With it having been International Women’s Day last week, I’ve been thinking more than ever about how to explain “Indian women” to the rest of the world. It’s common for an Indian abroad to be interrogated about the status of women back home – and small wonder given the outrageously misogynistic rapes/dowry deaths/acid attacks that are part of that story. But the story is such a complex one that a single answer is inevitably inadequate,

So, for this week’s post I’ve decided to tell you about my paternal grandmother, who was born more than a 100 years ago in 1910. We are only two generations apart and yet the distance between us yawns in a seemingly unbridgeable manner. And it’s as good an answer to the story of Indian women as any.

This is a photograph of my grandmother, Bhagyam (born in 1912 - on the left), and my great aunt, Alankaram. I never met the latter and my grandmother died when I was little, but they have such remarkable stories: microcosms of epochal change.

Alankaram was a child widow who was rescued from the kind of living death that was the lot of little girls whose "husbands" had died before they had even met, in India at the time. To protect so-called family honour and family property, Hindu society had long disallowed the remarriage of widows, even pre-pubescent ones whose marriages had never been consummated. Once their “husbands” died, these girls had to spend the rest of their lives wearing white saris, give up material comforts and live a stigmatized, isolated existence. The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856, had changed some of this in theory, but in practice the plight of child widows was still dire, at the start of the 20th century.

Luckily, my aunt, Alankaram, was taken in by Sister Subbalakshmi, a social reformer, who had set up a home in Madras for the education of child widows.

In the meantime, my great grandparents died in quick succession leaving my grandmother, Bhagyam, and two grand uncles, orphaned. They were now at the mercy of relatives who treated them poorly. The boys were sent to school, but my grandmother was about to be married off at the age of 10 to someone decades older.

It was then that her sister, Alankaram, staged an intervention with the help of Sister Subbalakshmi, to prevent this. It unfolded in a wildly cinematic episode, involving the abduction of Bhagyam from the village home (in Sulamangalam, Tamil Nadu) of the relatives she was living in. She was spirited away from the house by bullock cart. The relatives, once they had realised what was going on, gave chase (also on a bullock cart). Picture that!

As the train to Madras puffed out of the village railway platform, Bhagyam was literally pulled in two directions- by Alankaram inside the train, and one of the recalcitrant relatives outside it. She was eventually yanked inside, to safety and an equally operatic future.

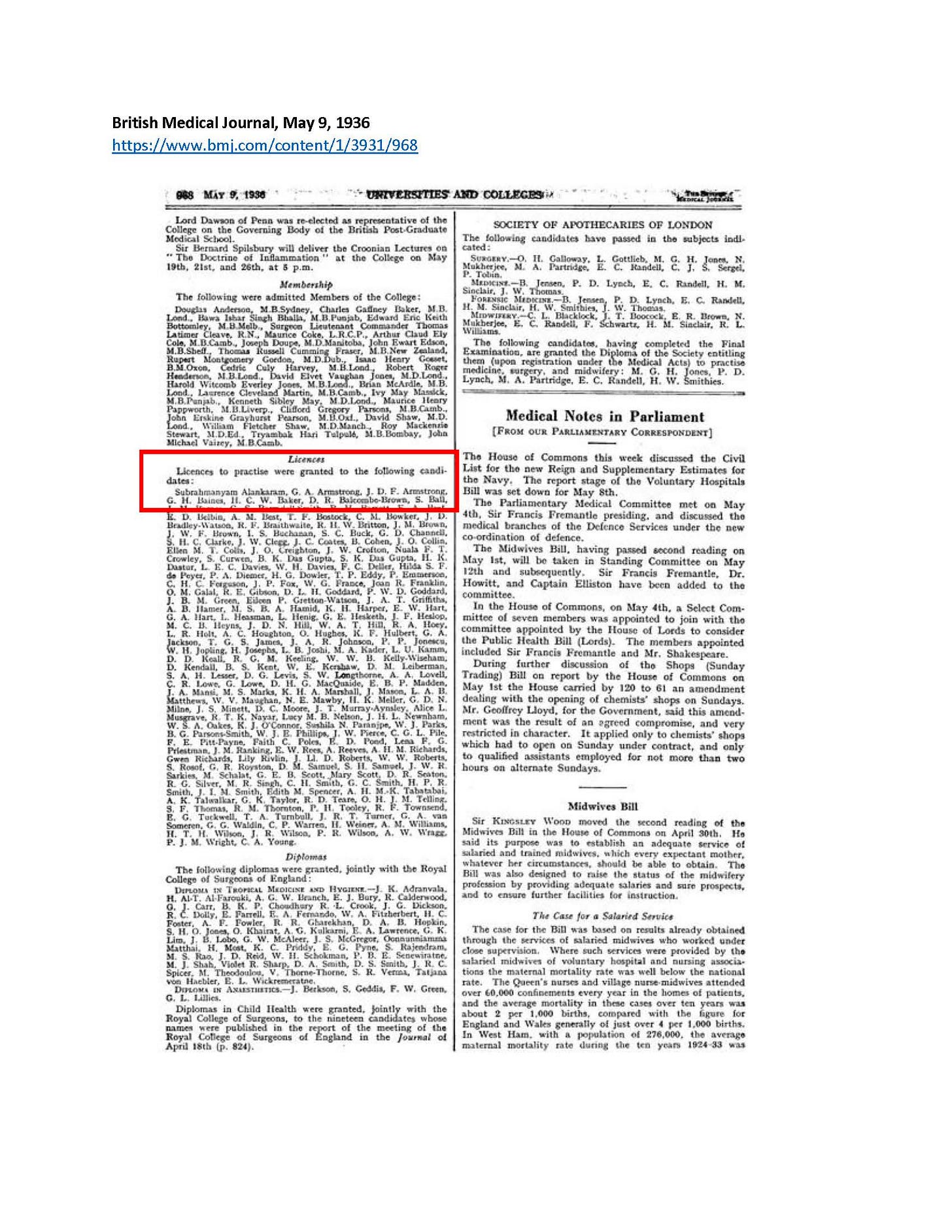

My great aunt Alankaram went on to become a brilliant doctor. She studied for and got her MRCS (Membership of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons) in London. Eventually, she rose to become the medical superintendent of Agra hospital. She married a Muslim, Uncle Mirza, who has his own fascinating story. Another time. Below, the entry for my great aunt’s medical degree in the British Medical Journal of 1936.

My grandmother was educated on scholarships at Sister Subbalakshmi’s school before getting her B.A. in Chemistry from Queen Mary’s college, Madras University. She went on to join the Madras Education Service. Following postings in the cities of Visakhapatnam and Nellore, she was able to raise a loan to enable her to go to England for a teaching degree.

Bhagyam set sail from Bombay on an Italian ship, towards the end of 1939. The ship was passing through the Red Sea when World War II broke out, leaving it stranded between Aden in the south and the Suez in the north, both of which were British held. The ship captain made the decision to take all passengers to Massawa, which was in Italian held Abysinnia (Eritrea today). He abandoned the ship, and all the passengers were left stranded. My grandmother had to return to India without having made it to England, robbed of all her possessions, with only the sari she was wearing.

There is much more. Some of it is detailed in a 1967 book by Dr Monica Felton called "A Child Widow's Story."

Disclaimer: Different members of my family have differing memories of the exact details of this story, but the idea of this post is to give some sense of the epochal changes an Indian woman, like my grandmother, lived through - from child marriage and orphaned servitude, to higher education and solo travel abroad. Bhagyam eventually brought up four children, in large part as a single mom, my grandfather having died in a plane crash when my father and his siblings were still little.

Three of her children went on to be educated in Oxford or Cambridge.

An uncle sent me a newspaper clipping a few years ago, that talked about a book of children’s poetry in Tamil that Bhagyam had written. I hadn’t known about it, until I read the piece.

****

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading. And do share family stories in the comments sections. These are so easily lost, its frightening. Our grandparents lived and acted in a world that was hugely different from ours- yet there is this direct line between us that needs to be remembered and honoured.

Finally, this newsletter relies on your subscriptions, so please DO upgrade to paid subscriber, if possible. And, as always, share.

Hasta pronto,

Pallavi

Thank you Pallavi, for your article which shows how right we are to celebrate womans day. Womanhood has been a sad tale of oppression in various forms, but fortunately the tide is turning in most of the world.

Your article reminded me of my own paternal grandmother - Alamelu Ammal.

Alamelu was married off when she was a child and was a widow in her early teens. Childless, she adopted my dad when he became an orphan. She was a wizened old woman with a shaven head and wore a colourless grey sari in the traditional Brahmin style.

Growing up as a child in Madras, - an extremely naughty child at that - she was someone I mocked and played pranks on. She was often engrossed in prayers and made little demands on the family. I was never curious about her or her life and never really understood why my father insisted on her living with us.

She passed away sometime in the late 70s when I was at university. I guess I should have talked more with and she had surely told me things about life way back in Trivandrum in the 1930s. She surely had a treasure trove of old oral history, memories and older family members I had never gotten to see. How I wish I had taken the time to speak more to her...