Political correctness and the decline in the generosity of listening

Affront is taken more often than it is intended.

Dear Global Jigsaw,

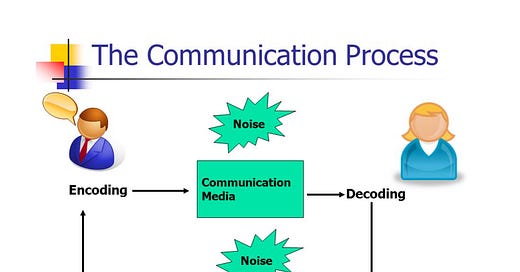

I teach a class at a leading university in Madrid in cross-cultural communication. I begin the course with explaining how every communication encounter has an encoder - the “speaker” - who is trying to convey some information, and a decoder - the “listener”- who is the intended recipient of that information. Miscommunication occurs when the message is not decoded as the encoder intends.

The likelihood of these communication breakdowns increases the further apart the speaker and listener are in terms of their cognitive lenses or implicit norms. These refer to the information and perspectives that every person has about the world they inhabit. Potential divergence between encoder and decoder is deepened along axes of gender, class, religion and national culture. My class focuses on this last parameter, given that communicative confusion is especially common in cross-cultural encounters. Every traveler has a story to tell. Do share yours.

Some examples I use in class include:

· An Indian who looks at traffic in China is likely to “see” it as orderly and disciplined given that her implicit norm of traffic in India is much more chaotic. However, a German looking at the same traffic in China will “see” it as anarchic, since his cognitive lens is shaped by norms in Germany.

· A Spaniard who kisses a new acquaintance in greeting is encoding friendliness, but it may well be decoded as scary or inappropriate by someone whose cultural customs preclude physical contact with non-intimates.

· A British person who smiles and says, “How lovely!” might in fact be encoding an emotion that approximates the opposite of, “How absolutely shit!” A decoder unschooled in this variety of irony would likely misunderstand.

· A Spaniard says let’s have lunch on Friday to a Swede. They agree. But in fact, they have agreed to different things. The Spaniard’s implicit norm equates “lunch” with an activity that takes place at 2:30pm, while for the Swede it is going to happen closer to noon.

· A French lady tells her monolingual American friend not to wait for her, because she is “retarded.” She is encoding “late,” since in French “en retard” means “to be late.” The English-speaking decoder will understandably be miffed. His cognitive map will not locate retards and people who are running late in the same place.

xxxxxxx

The class I teach is to MBAs many of whom will eventually work for global companies with a culturally diverse workforce. The students are keen on learning about cultural differences so as not to inadvertently insult someone from a different background. They want to gain the skills necessary to frame their message in a way that is congruent with the decoder’s culture.

When it is appropriate to bow rather than kiss, for example, or with which hand to exchange visiting cards. They wish to know how to address their interlocuter in a manner that will not cause offence. Are first names better or honorifics? The emphasis is on trying to make sure not to give the decoder any opportunity to take umbrage.

What is left out of the conversation is the responsibility of the decoder. In class, as in western society more broadly, there is an increasing imbalance in the onus placed on the encoder versus the decoder. The speaker over the listener. The skills needed to decode a message as it was intended, by thinking about the cultural norms of the encoder, rather than rushing to take offence are not in demand. We are constantly reminded to be careful of how we speak, and no doubt to do so skillfully is important, especially so in a multi-cultural context. But what about learning to be a generous listener? To decode with care? This is equally a vital skill for inhabiting a globalized world, but one that seems to be devalued in the pedagogy du jour.

But as someone who has lived in eight, culturally diverse, countries, I think the most valuable skill I have garnered in the process is not just knowing how to encode messages in a way that they are understood as intended, but to be large-hearted in my decoding. Cultural intelligence is about acquiring multiple cognitive lenses that allow you to put yourself in another’s shoes. As an encoder one should be aware of where the decoder is coming from, but equally, as a decoder there needs to be a sensitivity to the encoder’s cultural context. Affront, I have found, is taken far more often than it is intended.

xxxxx

There are two types of foreigners – expats and immigrants. The former: wealthy and entitled, tend to be encoder focused. To them it is incumbent on speakers to communicate with them in a way that they approve of. An Indian friend recently complained to me about his Argentine colleague who upon learning that the Indian did not eat beef, quipped that this was because my friend was yet to “try Argentine beef.” The Argentinian clearly lacked competence in Indian cultural norms. Many Hindus do not eat beef, and this is a non-trivial, religious matter for them. But were the Indian to have put himself in his colleagues’ shoes, he might have discerned friendliness, rather than offence. Argentines take pride in the quality of their beef and wanting to share it with those who may never have tried it is an offensive sentiment only of the listener lacks the ability and crucially, the inclination, to be able to decode it with intent, rather than affect, in mind.

I had a student from the United States complain the other day that often when she tried speaking to Spaniards in her less-than-perfect Spanish, her interlocuters switched to English. “It’s very rude,” she concluded. “Perhaps they are trying to be helpful?” I countered. This was a conversation that put me in mind of a Chinese-speaking British friend in Beijing who always complained how the moment he said, “Ni Hao,” Chinese people would complement him on his Chinese. “It’s patronizing,” he’d concluded. I’m quite sure it was in fact complimentary. Again, in Japan when a Japanese person chose silence rather than debate as a response to an assertion made by an expat, it was often decoded as lack of critical faculty, when what was being encoded was respect.

Immigrants on the other hand, are less curmudgeonly as listeners. They do not have the luxury of the belief that they must be spoken to in a way that matches their norms, norms which are often different to those of the politically correct West, to begin with. Punjabi farmhands in Italy, Bangladeshi fruit sellers in Spain, Chinese masseurs in Australia and Congolese hairdressers in Belgium are better attuned to intent than their white collared counterparts. They become expert decoders.

In Spain, where I live, for example, it is so common for general stores in big cities to be run by Chinese immigrants that they have come to be known as “Chinos” or “Chinese.” People say they will pop around to the “Chino” to pick up some bread. My North American students are appalled at this label. According to their norms, the conflation of the stores with an ethnicity is an instance of casual racism. But when I asked an acquaintance from Wenzhou who works as a masseur in Madrid about what he thought, his response was to giggle. “Most of the stores are run by Chinese,” he said. “It’s a fact. No harm is intended. People here don’t have enough real problems.”

xxxxx

Cultural codes are complex. For instance, while kissing in greeting, especially across genders is rare in Asian contexts, it is very common as a way of expressing affection towards children, even those whom the kisser might not know. In India, a baby is fair game for would-be cheek pullers. The kind of worries about pedophilia and stranger-danger that are rife in the cognitive maps of people in the “West,” often do not show up in the equivalent maps of peoples in the “East.” It is common in most Asian countries for random strangers to reach out and stroke a cute baby’s hair. The stroker is encoding her appreciation of the baby’s cuteness. And babies are seen in some subliminal way as a communal bounty. But it is quite possible that a Norwegian tourist in India, for example, might decode this communicative encounter as grounds to initiate a police case.

Growing up in Asia, my sons, being poster boys for the sort of Eurasian look that was much prized, had to get used to the (literal) embrace of strangers. On a visit to China when Ishaan was about eight years old, he was mobbed in a village we visited in the Pearl River Delta, not far from Shanghai. People queued up to take photos with him. He was also regularly cuddled by hijab-wearing aunties on buses in Indonesia, when we lived there. “Cantik! Beautiful boy,” they would say while reaching out to grab him. The fact is that my boy did not particularly enjoy being hugged. Yet, even as a younger person he intuited that the attentions of the old ladies of Jakarta, and the excited village folk of China, while unasked for, were far from ill-intentioned. That they were encoding niceness and being a collector of multiple cognitive maps, he was a generous decoder. It was a matter of weighing the slight discomfort he felt at the encroachment of his personal space, against the kindness he’d be doing to the strangers by acquiescing to a hug or a photograph.

xxxxx

Ultimately, cultural intelligence lies in a balance between encoding and decoding. Between someone’s right not to be offended and their obligation to understand intent. An overweening emphasis on either end of the communication encounter can only lead to virtue signaling when what this beautiful, diverse and culturally rich world needs is real dialogue.

xxx

I hope you found some food for thought in today’s newsletter. If so, please do share it with others who might find it interesting. Also, as usual, I would love to hear your thoughts on the issue. Finally, a paid subscription helps me to keep writing. You guys are my employers in this brave new media world.

Fascinating... lots more to say, you could turn this post into a book!

Thank you Pallavi, our políticisns should attend your course, they can neither encode or decode…😎