Language matters to how both nations and individuals understand themselves. Wrapped up in a nation’s idiom(s) are questions of power, opportunities and identity.

Last week, I began my post on “Being Indian in English” by alluding to how I often get asked if I speak “Indian,” by non-Indians.

“Why don’t all Indians speak Hindi?”

My first memory of trying to explain my country’s byzantine linguistic ecosystem was to a Chinese student at Peking University circa 2002. The girl in question was a Hindi-language scholar who was beginning to realize that English would be more useful to her than the language she’d spend the last several years learning, when it came to job prospects in India.

“Why don’t all Indians speak Hindi?” she’d asked me grumpily.

I had tried to explain India’s embrace of multilingualism, its 22 official languages and its lack of a national one, by talking about diversity and the unfairness of prioritizing the tongue of some Indians over those of others.

She’d stared at me blankly, unable to comprehend the idea that a country could be coherent in the absence of a unifying tongue. The idea that a nation requires a national language to act as a glue felt as obvious to her as stating that the sun was hot.

In fact, there is nothing obvious about the choices that different nations make when it comes to languages. The process of arriving at these decisions is often a fraught one, both crucial and controversial, made especially so in the context of polyphonic and geographically diverse countries like China, India and Indonesia – three large Asian nations that I’ve lived in.

The making of “Chinese”

In China, the Communist Party under the leadership of Mao Zedong, pushed for Putonghua, a newly standardized idiom based on the language spoken in the nation’s capital, Beijing, to become what we now refer to as “Chinese.”

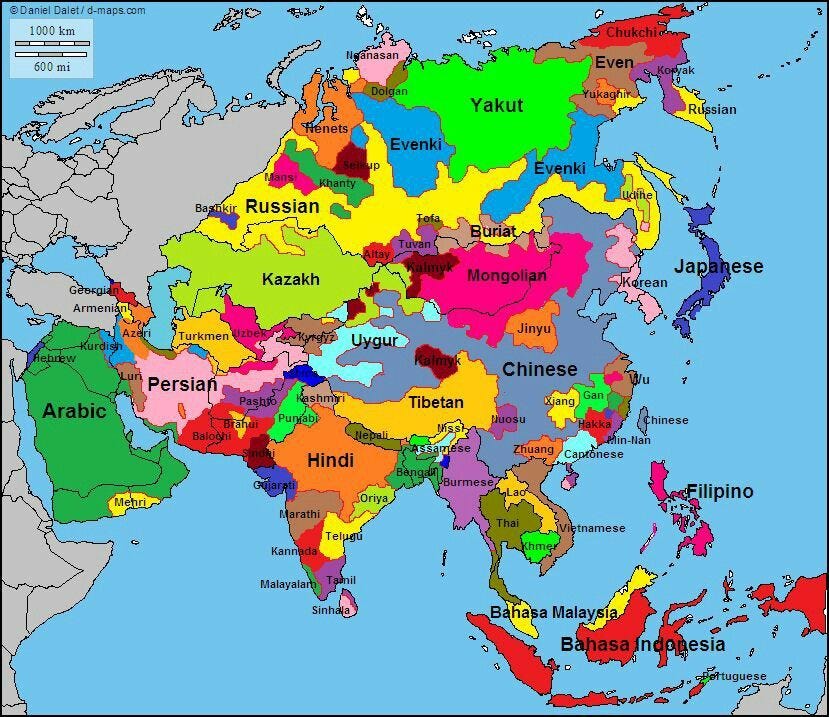

This took considerable social engineering to achieve. Prior to the 1950s, Han Chinese spoke nine main tongues that were in large part mutually unintelligible when spoken. These included Mandarin - which became the basis for Putonghua, Wu (of which Shanghainese is part), Xiang, Gan, Jin, Kejia, Yue, Northern Min and Southern Min (these last two are not always considered as separate), each with many sub dialects.

Moreover, non-Han peoples spoke an additional 300-odd languages including Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang.

In order to consolidate state power, facilitate communication between the Chinese peoples and to promote literacy, Mao Zedong “reformed” Chinese to make Putonghua (literally- the common speech) the national standard. Concomitantly, Chinese characters were also simplified in the manner of their writing, to make them easier to learn. It was only in 1982, when a revised constitution was promulgated, that Putonghua (the Mandarin Chinese of today) secured its place as the standard national language without any real competition.

India: a nation without a language; or an excess of them?

In contrast, in India the initial intention of the postcolonial state - to adopt Hindi as the national language - was abandoned following massive protests and riots against its imminent imposition on the country. Hindi is a northern language that belongs to a different linguistic group to the languages spoken in southern Indian states. There are currently 22 official languages in India, and no national language.

The contrast between India and China’s linguistic trajectories highlights their strengths and weaknesses. India’s reflects its choice of democracy and diversity at the risk of messiness and centrifugal tendencies.

China, where the ability to impose a single language was facilitated by a common writing system, reflects the prioritization of a strong state making decisions in the long-term “interests” of the nation, untrammeled by the inconvenience of the vote.

Indonesia: A third way

And then there is the case of Indonesia. A sprawling archipelago of over 17,000 islands, Indonesia is home to some 700 languages, many of which do not share scripts or linguistic roots. Like China, independent Indonesia also chose to adopt a single national language: Bahasa Indonesia.

What made this choice quite remarkable is that it was neither the language of the majority of citizens, nor of the political elite. Those labels belonged to Javanese, a language spoken by most of the inhabitants of Java, Indonesia’s most populous island and the centre of gravity of its nationalist movement.

Bypassing its majority language, Javanese, in favour of a variety of Malay, whose standardized form was dubbed Bahasa Indonesia, or the language of Indonesia, was an unusual choice. The many Javanese nationalists involved in the discussions at the time not only acquiesced, but actively advocated Bahasa Indonesia as the logical choice for a national language.

Malay had functioned as a lingua franca across the archipelago for centuries. By the time it was officially adopted by the Indonesian nationalist movement in 1928, it had already emerged as a rallying symbol of resistance to colonial politics.

Malay’s role evolved in part due to the absence of a Dutch equivalent to Thomas Babington Macaulay, the man who introduced English language education in India. Under the Dutch colonial administration, “native” Indonesians were discouraged from learning Dutch, so that unlike English in India, the colonial language of Dutch was not of much use in enabling nationalist consciousness in Indonesia.

Malay, on the other hand, had long been used by traders across the Southeast Asian region as the language of communication. Indonesian nationalists were keenly aware of the need to avoid conflating nationalism with any single ethnicity or religion, given the complex plurality that they were attempting to weave into a coherent unity. Hence the engineering of a minority language, Malay, into the national language: the Bahasa Indonesia of today.

Bahasa Indonesia was also a simple and flexible language that had soaked up loan words from divergent cultural milieux. Traces of the influence of the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms that dominated the region for hundreds of years, of Arab and Indian Muslim traders, Portuguese and Dutch colonialists, can all be found in the Bahasa (itself derived from the Sanskrit word bhasha or language) Indonesia vocabulary. Its amalgamation of words, borrowed from Sanskrit, Javanese, Persian, Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese, Dutch and English, is synthesized with a no-fuss grammar, and written in the Roman script.

Language and literacy

Choosing a simplified national language as China and Indonesia did, arguably helped increase literacy in these countries. When the communists took over mainland China, the adult literacy rate in the country was below 20 percent. It is now over 96 percent. Indonesia boasts a similarly impressive trajectory. When Jakarta declared its independence from the Netherlands in1945, only five percent of Indonesians could read and write. This figure is now up to over 95 percent.

In contrast, the adult literacy rate in India remains low, at only 77-odd percent. Although a marked improvement from the 20 percent literacy the country began its post-colonial inheritance with, it’s possible that the sheer abundance of languages in India and their varying importance to personal success: local, regional, Hindi and English, have hampered policy efforts to improve literacy.

On the other hand

It isn’t all good news for single national language nations, however. Smaller language groups in countries like China and Indonesia are threatened to a greater extent than in India. One of every four Indonesian languages, for example, is considered endangered. Although many Indonesians still speak local dialects, when they write it is almost exclusively in Bahasa Indonesia. There hasn’t been a daily newspaper in Javanese, the “native language” of the archipelago’s largest ethnic group, for decades.

(I wrote a piece back in 2007 about the near-death of Manchu as a language in China, here.)

**********

The language-nation link is thorny. India might have avoided Balkanization and therefore ensured its survival as a nation because it eschewed a national idiom, in effect strengthening its political viability by allowing linguistically centrifugal forces.

I currently live in Spain, a country where a secession movement in the region of Catalonia has gained ground in recent years, in major part on the basis of separate linguistic identity. In the past I lived in Belgium, a tiny country when compared to the Asian giants I’ve been discussing, but one that has continually been wracked by linguistic nationalisms since its creation in 1831. See below:

******

Dear Global Jigsawers, what do you think of the importance of national languages? Can you conceive of somewhere like India, that lacks one? Should language be the basis for a separate national identity? Let me know in the comments section.

As usual, please share this on your social media if you found it interesting. And do consider subscribing.

Content is a product like any other. And just as you would consider it “normal” to pay for a cup of coffee at a café, do consider a small fee for consuming the content you read online as well. There is work that goes into it and I hope you agree that good writing on interesting topics is an endangered species, given the sea of click bait we are all swimming in. It needs your support.

Until next week.

xo

Pallavi

The conundrum of multi-languages is something I grew up with. My "mother tongue" was Swahili (now forgotten), my first son's was French, my second son's was English, they speak German at work etc. For example, Belgium has three official languages, Switzerland four, Spain three too. It's easier to get along when you have 300 languages than when you have 2 or 3. In Belgium, the fight came not about the languages themselves but about the social status they had: French was upper class, Flemish was peasant/lower class, whereas German was considered OK. It's a long story of Middle Ages dominance and shifting sovereignty. In the UK, it's the accent that matters and it's unfair to a huge slice of the population; language as a social status instead of a means of communication and exchange is the crux.

There is more to say, but that will be for next time.

I live in India and I certainly don't think that Hindi should be imposed on all. Since, I work for the government, I have encountered the challenges involved in having multitude of languages several times. A lot of effort and resource goes into translation that may not even be very good in terms of quality. Language is also used for political grandstanding. Truly a conundrum for which I don't know if there is any solution.