Hola a todos,

Its Global Jigsaw Monday. I hope everyone had a good-ish weekend. I have my mum visiting me in Madrid, so mine was quite lovely :-)

This last week I gave a TEDx talk at Madrid’s impressive, IE university. The theme for the event was “One step back, two steps forward.”

Pallavi Aiyar at TedxMadridIE. Photo credit: Julio Arias

My life, and I suspect most of yours too, has been one long dance of shuffling back and forth, so it was an idea that resonated with me. Here is the text of the talk. Let me know what you think.

Multiple lenses in a polarized world

We view the world in a way that is influenced by our implicit norms or internal lenses, which are determined by our cultural, socio-economic and national contexts. These set the parameters for what we think of as normal.

Is it normal for you to turn on the tap and drink a glass of water?

Is it normal for you, as a woman, to go out for a walk in the evening?

Is it normal for you, as a student, to have to pass through a metal detector before making it your classrooms?

Clearly, what is normal for one person, in one context can be absurd for someone else. But this is not always apparent to us. We are wired to think of our implicit norms as universal.

I was born in India and lived there until the age of 20. This meant that I was privileged when it came to the awareness of the existence of multiple normalities. There is, for example, no language called “Indian.” In India there are 22 official languages, and we are a tapestry of ethnicities, religions and traditions.

In addition, I spoke English as a first language. This meant I had access to the implicit norms of the English-speaking world, which were markedly divergent from my lived reality. When Shakespeare compared a woman to “a summer’s day,” he was obviously not talking about a summer’s day in India- which was horrible and would be an insult rather than the compliment he intended.

After school, I followed the tried and tested path for an Indian of my background and went to the UK to study. I returned to my dream job as an on-camera TV reporter, something I’d aspired to since middle school. And guess what? I hated it. For me, TV news lacked depth and was on permanent pot-boiling-over mode, so that I rarely had the time to actually tackle any issue in depth.

It may sound terrible to discover that you hate the job you’ve always wanted, but everyone should be so lucky as to hate their first job. Because it is only then that you begin to grow the wings needed to fly.

So, what did I do? I took a step back and returned to university for a Masters, where serendipity arranged for me to meet with Julio, a Spaniard with a passion for China. And so began the journey I have been on for the last two decades, of taking many steps back, to make bigger leaps forward each time.

In 2002, I moved to China to be with Julio, who was working there by then. The country was a conceptual black hole for me. I didn’t know the language; I had no connections or friends there. It was a risk, and a pause in my promising career. But one that opened up many opportunities that would have been unimaginable had I not taken that risk and pause.

I became the China bureau chief for one of India’s leading newspapers. I was the only Chinese-speaking Indian foreign correspondent covering bilateral relations between what constituted a third of the world’s population, at a time when China’s importance was exploding globally.

I soon realized that I saw China fundamentally differently to how my western foreign correspondent colleagues did, because my implicit norms were fundamentally different to theirs.

Let me give you two examples. The first is the traffic in China.

Now, to a German the traffic in Beijing was chaotic, unruly, as though no one followed the rules. But to an Indian, the same traffic appeared orderly. An Indian marveled at how everyone followed the rules. Same fact- totally different conclusion.

The second has to with the run up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Both my western foreign correspondent colleagues and I were shocked to discover that the official in charge of the Organizing Committee for the Games, had been charged of large-scale corruption, sacked and arrested. But while the western journalists were shocked by the corruption, I was shocked by the fact that he has been sacked and arrested.

My “normal” was one where the powerful could operate with impunity, regardless of all manner of corruption charges.

After spending eight years in China, I moved to Belgium, the headquarters of the European Union. In Brussels, protests outside the EU headquarters were part of the scenery. Farmers, fishermen, taxi drivers, dockworkers were always striking demanding the retention of subsidies and other protections. When I looked at them with my China/India-habituated lenses I found it harder to sympathize with the protestors than my European counterparts did.

These were not malnourished coal miners from northeast China whose families were dying from lung cancer. They were not tribal women from India’s forests whose lands had been appropriated by rapacious coal mining company bosses. They were the crème de la crème of the global labour elite, fighting against any loss of their substantial entitlements. I wondered if they realized just how privileged they were. They didn’t.

But over time, I learned to also have sympathy for them; to see the decline in their relative position in the world and the relative loss of their livelihoods with understanding. Comforts and privileges are normalized with remarkable ease. This is hardly unique to Europe. It is always harder to give up something you once had, than to make do without something you’ve never had.

I added a European lense to my growing collection of lenses.

Over the next ten years, I went on to move to Indonesia, Japan and now, Spain. These moves were for my husband’s job – he was a diplomat. As you can imagine, this could feel very negative. It was fertile ground for resentment. It was easy to complain about the lack of agency and the inability to control one’s own choices. The term “trailing spouse” is infused with the echoes of a laundry-list of sacrifices.

But I chose to see every move as a gift. For how could it be otherwise, when I was being presented with multiple opportunities to expand my identity, my ways of seeing the world, indeed my ways of being in the world?

With each move I experienced a process of loss, learning, and reinvention. There was the loss of income. And, often, of status. When you tell someone you are in a country because of “your husband’s job” your interlocutor’s eyes glaze over faster than you can say, “ni hao.”

There was also, at least in beginning, a loss of friendships. But for me this “loss” was a process of addition rather than subtraction. It was about taking that step back, that allows growth to take place. To grow one needs time for keen observation, reading, learning a language, listening.

There is a hallucinatory quality about your first few months in a new country. Your senses are almost chemically alive. When you have lived in a place for a long time, the extraordinary becomes habitual, and eventually invisible. But when you are new to a country – and I would argue this holds true for being new to any field of expertise – you are not yet desensitized.

When you walk down the streets you notice the manhole covers. When you sit a café you notice the body language of those around you – whether it is expansive or shrinking. You take in the titles of the books people are reading on park benches. And this period of so-called “loss,” becomes a time of great growth – intellectually and emotionally.

When you can never settle into a comfort zone and need to continually reorient, you end up being more than you were before. You begin to carry multiple worlds within you. And in a polarized world where we are increasingly divided into ideological silos, this skill – of putting yourself in someone else’s shoes - is increasingly rare, but ever more crucial.

It’s what makes humans special. It’s what AI will probably never have. Artificial intelligence might beat humans in chess. It might perform most managerial functions better than human managers. But where humans trump machines is in the ability to have empathy. And developing empathy is never a linear process, but a constant shuffle of steps back and forward.

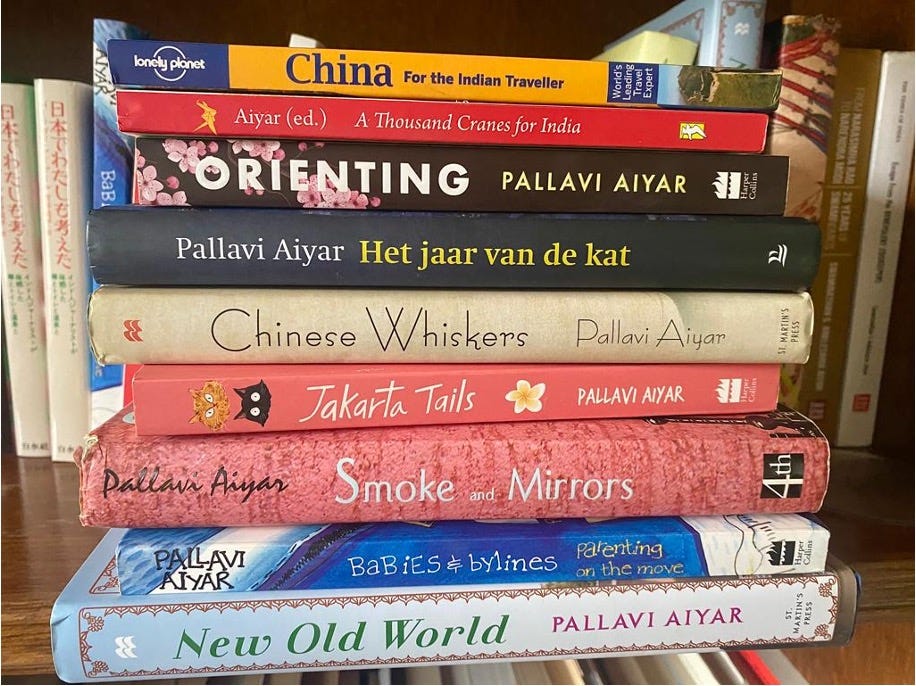

I have gone on to report on every country I’ve lived in, and written multiple books - both non-fiction and novels - about them. I’ve made it my life’s work to join up the dots and to train myself to see bridges, where others see fences.

The “truth” is always multiple and messy and does not fit into tidy boxes. The “truth” moreover, has as much to do with the observer than the fact itself. Your failings, your predilections, your biases and understanding of “normal.”

To reach this understanding might require one to take step back, but it is only by doing so that you will take not just two, but ten steps forward.

Thank you

*****

I am off to London later this week for a lif fest: JLF London at the British Library. Swing by if you are around.

Hasta la proxima semana,

Un abrazo fuerte,

Pallavi

PS: Subscribe, will ya? And share, share, share. xo

En este mundo traidor, nada es verdad ni es mentira, todo depende del color del cristal con qué se mira.—Pedro Calderón de la Barca, La vida es sueño, 1636.

Thank you for another great post. As you say we all look at the world through our own lenses...Religion has coloured most lenses for centuries;¿Is secularization making the world a better place?