The Australian Weighing Machine maven of Calcutta

Of fortune telling, weight, railways stations and serendipity in Jakarta

Dear Global Jigsawers,

I am just back from a fabulous trip to Napoli, a city aptly described to me by a friend as “Calcutta with baroque.”

More on Napoli very soon, but first, another Calcutta-linked story: one that embodies the cross-border connections that this newsletter is all about. It takes us from Australia to India, to Indonesia, and down memory lane as well, to the railway station weighing machines of my childhood.

******

Nostalgia transforms ordinary objects into talismans. Just the feel of the names of the “things” from childhood evoke pathos: a longing for the past, its innocent excitements and vast promise.

I grew up in the pre-economic liberalisation Delhi of the 1980s. Childhood in those days meant ambassador cars with seats so high that little legs couldn’t touch the floor. It recalls a white heat, relieved only by chilled banta, spicy lemonade in glass bottles, stoppered with a marble. There were Harrison talas with which to lock cupboards, and 150-gram Nirma detergent tikiyas with which to wash clothes.

There was also the railways station-weighing machine. This was a time when to travel meant taking a train. Airplanes were objects of almost unbearable, and unattainable, luxury. But train stations with their red-coated coolies weaving through the throngs, the balletic steam of spicy chai wafting in the air, the aural assault of people yelling out to each other to be careful and eat well and not to forget to write, were an intrinsic part of the weft of life.

For me the greatest thrill was receiving a 1 rupee (or was it 50 paisa?) coin from my parents to slot into one of the ubiquitous weighing machines that dotted train stations. Once the coin was in, the multi-coloured pinwheels behind the glass casing along the semi-circular top of these machines began spinning like manic ballerinas accompanied by all manner of whirring and pinging.

Photo Courtesy: Indian Railways Fan Club Association

Rows of green, red and blue lights flashed. And then out came a rectangular ticket-sized piece of cardboard with not only one’s weight printed on it, but also a fortune.

The fortunes were almost always optimistic, their language dignified. Sometimes I couldn’t understand the words and only rarely understood the import. But at a time when I owned very few things, the fortune-weight tickets were mine. I hoarded these for years in my desk drawer.

“EAT well and thrive,” one said. A tad ironic given that this was a weighing machine?

“JOVIAL in disposition and cordial in manner, your passions are healthy, spontaneous and without inhibitions,” read another.

“SUDDEN travel and change of place may be imminent. Be prepared,” warned a third. Well, this was a railway station.

*********

The years rolled on. Fast-forward a few decades and I only rarely took trains anymore. I hadn’t seen a 1-rupee coin in forever. I was no longer overly keen to find out my weight.

The railway station weighing machines of my childhood were thus in the process of quietly disappearing from my memory, until a chance meeting with an Australian neighbour in the capital city of Indonesia, Jakarta. In the style of the weighing machine fortunes: TRUTH is stranger than fiction.

It was 2015, I think. I’d been living in a leafy, residential neighbourhood of south Jakarta for about three years when I received a note inviting me to a housewarming party next door.

That evening, I rang the bell of the immaculate bungalow that stood diagonally opposite ours and was let in by Raj, an Indian Malaysian whom I learnt had lived in Jakarta for close to a decade. His wife was a statuesque Australian, Michelle Somerville, the type of socialite who haunted the pages of magazines like Indonesian Tatler.

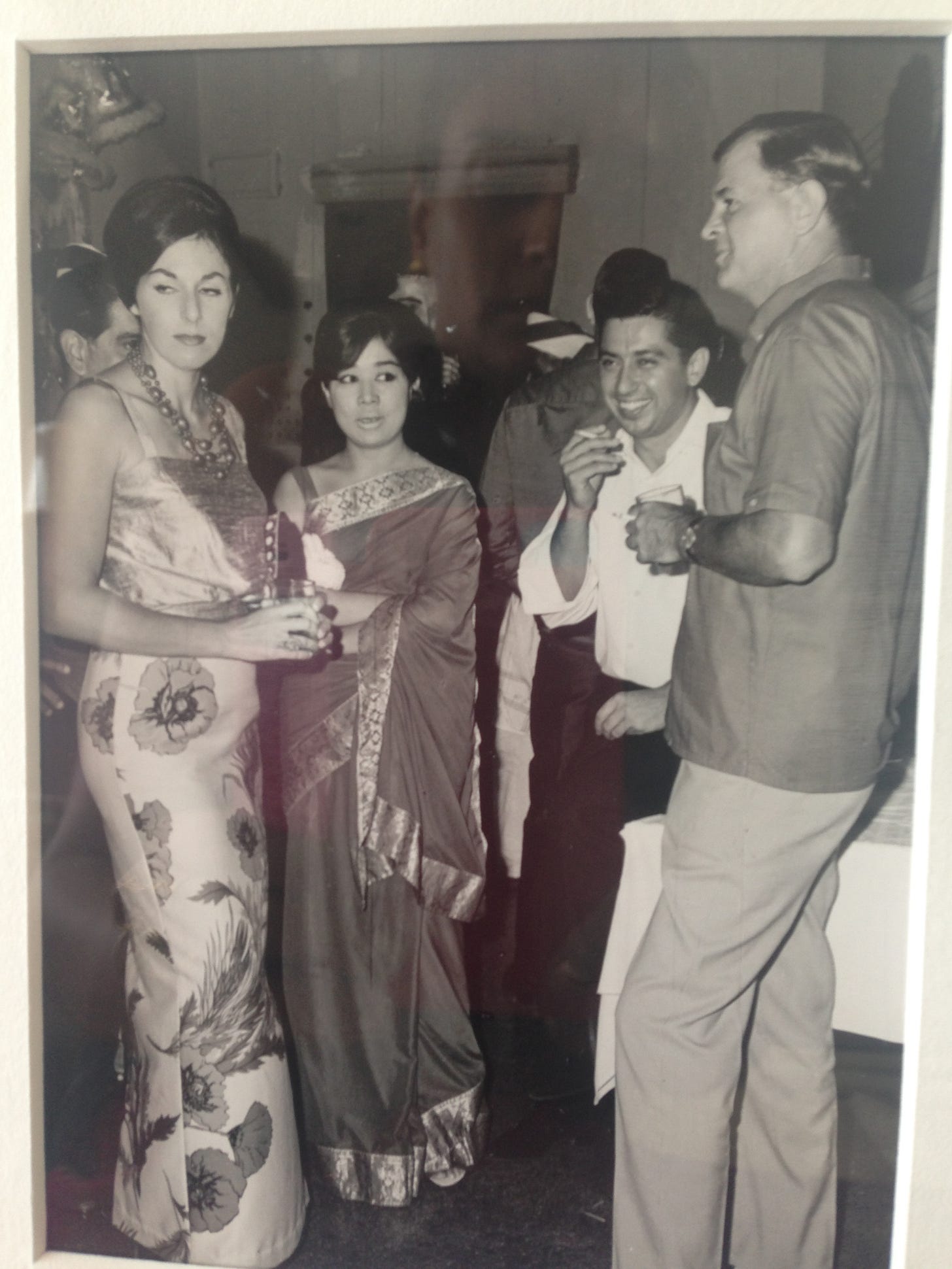

My mother and I with another friend and Michelle (extreme right)

I noticed a preponderance of Indians at the party that I ascribed to Raj’s ethnicity. It was only after we gradually became friends over the coming months that I realized the one with the deepest connection to India was in fact, Michelle. My Australian neighbour had grown up in Calcutta, the city that was home to her family’s manufacturing company, Eastern Scale Pvt Ltd, none other than the makers of my beloved railway platform weighing machines.

The company was established in 1939 by J.H. Somerville, Michelle’s paternal grandfather, an Australian of Scottish descent, who immigrated to India drawn by the lure of economic opportunity in the aftermath of the Great Depression.

He started out life in Calcutta importing miscellaneous goods, amongst them ticketing and slot machines, delicatessen scales, and railway weighbridges. At one point, machines owned and operated by Mr. Somerville printed virtually all the tickets to India’s major tourist attractions including the Taj Mahal and Victoria Memorial, as well as bus tickets around the country.

But it took a few decades for the signature weighing machines of my childhood to make their debut. Initially, Mr. Somerville simply imported huge, wrought iron weighing scales from West Germany. These were drab and lacking the carnivalesque accoutrements of later models.

But after Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi restricted the trading activities of Indian companies in the 1970s, Eastern Scales was forced to adapt by manufacturing its own scales. In an infusion of the tickets, coin slots, flashing lights, and weight displays that had characterized the company’s early imports, the railway platform weighing machines I remembered were born.

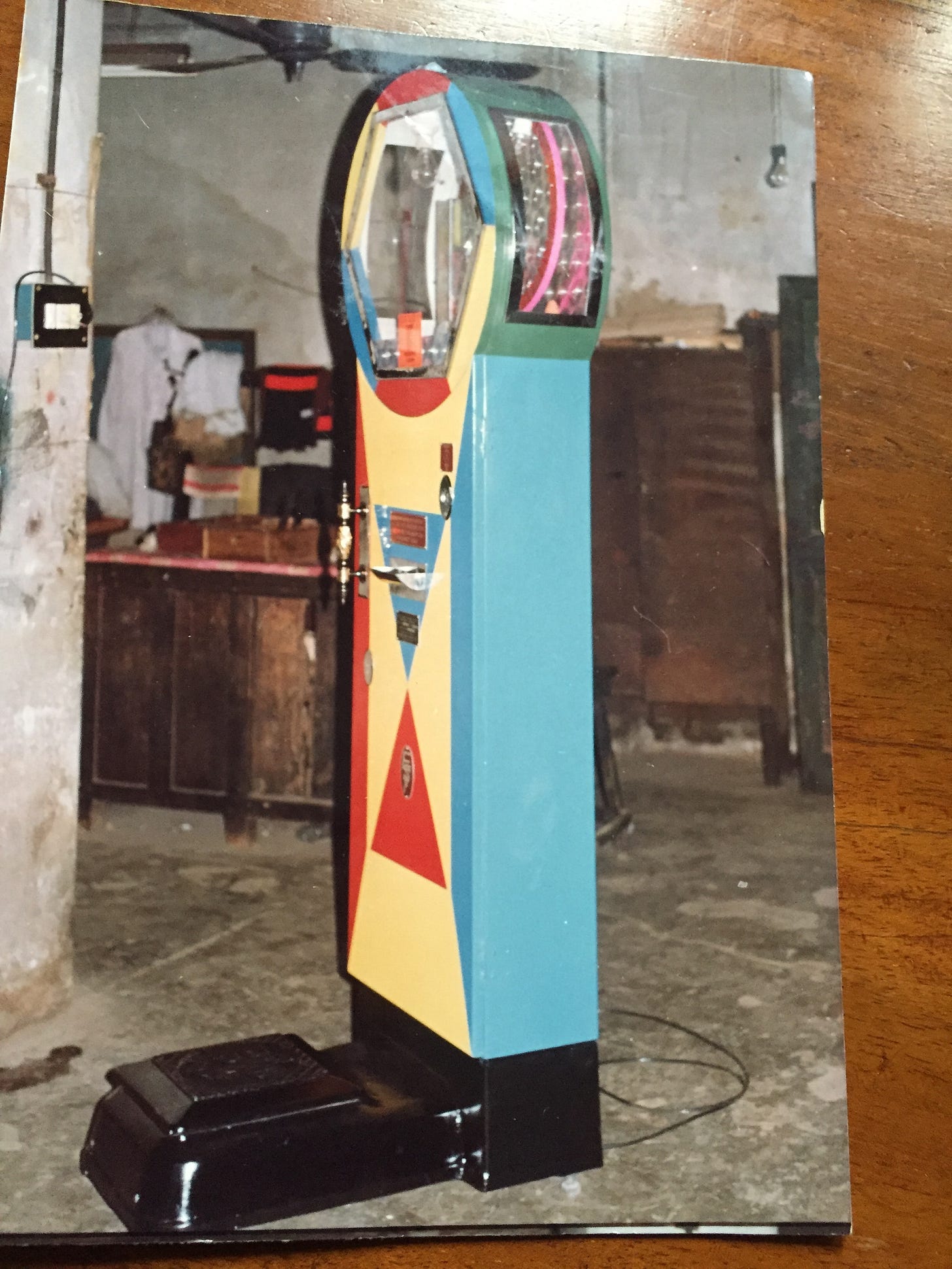

A weighing machine on the factory floor of Eastern Scales

Michelle had almost no memory of her grandfather who had died soon after she was born. But we spent a morning looking through old family pictures at her home one morning, over generous slices of plum cakes and a decadent glass of champagne.

I was particularly captivated by a shot of Grandpa Somerville and his wife, Grandma Dunhill (a relative of the eponymous cigarette dynasty) probably aged about 30. They were a dashing couple.

Grandpa Somerville and Grandma Dunhill

********

Mr. Somerville senior went on to have three boys, Jack who was the eldest, Bill and Jim. It was Michelle’s father, Jack, who eventually took over the reins of Eastern Scales from 1980, until his passing in 2004.

While researching this story I found a blog on a shipping website in which a British sailor posted his memories of meeting with a “tall laconic Australian,” Jack Somerville in Calcutta in the 1970s.

“Jack was quite high-up in the social pecking-order of Calcutta and introduced me to people who wouldn't, normally, even glance at me! One guy, who was a great friend of Jack's, was a very wealthy Indian called "Daddy" Mazda and I remember going to a party in his flat and was absolutely floored by the sheer luxury and opulence of the place. It had massive tiger-skins on the floors in the main sitting-room, which was absolutely huge, and the whole place just reeked of wealth and there was me!....Jack was rather partial to Scotch whisky and would come aboard whichever ship I was on and sink copious amounts of it and then get wafted home in his Ambassador driven by his driver.”

Calcutta parties in the 1970s

Michelle lived in Calcutta until she was seven years old, after which she studied in Hong Kong and Australia. Her memories of the time are hazy. She talked about her parents playing bridge at the Tollygunge Club. And being forced to take horse riding lessons even though it terrified her. Her afternoons were spent with her ayah whose job it was to bathe and feed her. It was only after little Michelle was made “presentable” that she was taken to see her mother in the evenings.

Michelle’s mother, Roberta Somerville, is now well into her 80s and still lives in Calcutta in the family bungalow. But Eastern Scales itself, has fallen into near bankruptcy. It’s been a somewhat precipitous decline.

Michelle and her husband, Raj, with Michelle’s mother, Roberta.

For example, as recently as 2001, the weighing machines made Rs 26 lakhs in the city of Mumbai alone, but by 2012 this figure had fallen to Rs 1.7 lakh. There are multiple reasons for this dip. The regularity and frequency of trains have improved in many cities, reducing downtime on platforms. More and more commuters now own scales at home. And the entertainment value of weighing machines is not much of a match for smart phones and iPads.

Michelle told me that she couldn’t imagine returning to India to try and revive the business. She finds India “stimulating to the extreme.” She was sad, nonetheless, that Eastern Scales’ days are probably numbered. “It’s like closing the door on an era,” she said with a wistful shrug.

A few days later she whatsapped me pictures of some of the fortunes that her grandfather had composed himself. I found myself tearing up.

“YOU will emerge triumphant from your most serious reverses. A happy and comfortable old age.”

“IF you are a women (sic) you have a rare unapproachable delicacy, poise, and a charming manner.”

I felt an ache. Just as meeting Michelle had jogged my memory about those magical moments on railway platforms when I was little and the future vast, I had simultaneously become aware of their imminent demise. There is pain in the impermanence of objects for it only points to our own ephemerality. Eventually, it was one of Michelle’s grandfather’s fortunes that cheered me up:

“YOU have a great reverence for the past but an exaggerated idea of its virtues.”

****

Hope you enjoyed this global story of serendipity and connections. If so, I’d appreciate your upgrading to a paid subscription. It only costs about a cup of (fancy) coffee a month, and it would enable me to continue writing this newsletter. If you are unable to subscribe, do share on your social media, so we can continue to grow of community of globalists trying to fit the jigsaw pieces together.

Until next week – when I’ll write about Naples,

Pallavi

* A version of this story has appeared in The Indian Quarterly.