Dear Global Jigsaw Family,

I am just back from a trip with some of my Spanish girlfriends to Rajasthan and it reminded me of the last time I was there in 2022. That was a trip that had my family converted to the camel. As we had traveled west, deep into India’s Thar desert, our car increasingly had to share the road with this awkwardly shaped ungulate, all humps and joints and teeth.

In Bikaner, we’d visited the National Camel Research Centre. The boys had tried flavoured camel milk and we learned that camel bone made a good replacement for ivory. In Jaisalmer, we rode camels over the sand dunes under a setting sun, and later, Ishaan bought a hand painted T-shirt of what can only be described as a camel high on hashish.

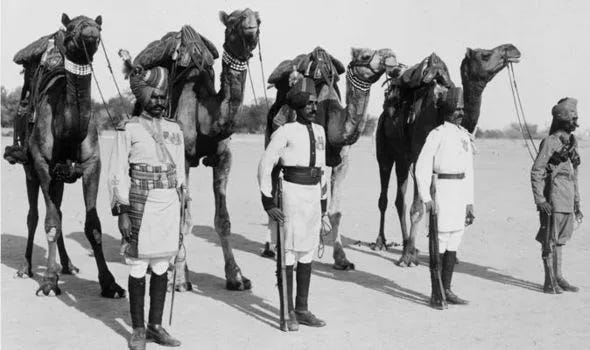

Rajasthan is synonymous with the camel. It is a region of camel polo and camel fairs. The Bikaner area even boasts a camel cavalry; one with a storied history. Under the British Raj, the Bikaner Camel Corps had played a role in putting down the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. And in 1915, during World War 1, the corps routed the opposing Turkish forces at the Suez Canal in a dramatic camel cavalry charge.

Today, the Indian military’s camels are mostly ceremonial, but camel-mounted soldiers from India’s border security forces still use them to patrol the more arid parts of the India-Pakistan border.

The Bikaner Camel Corps during the First World War

And yet, camel demographics in Rajasthan are worrying. On this recent trip, I cannot recall seeing more than a handful of the animals. We have returned with photos of cows and buffaloes, an elephant, and droves of langurs, but no camels, something that would have been unthinkable following a tour of Rajasthan, even as recently as 2022 when I visited with my boys.

Worldwide, the camel population has risen from nearly 13 million in the 1960s to more than 35 million, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, which declared 2024 as the International Year of Camelids to highlight the key role the animal plays in the lives of millions of households in more than 90 countries.

But their numbers are on a drastic decline in India – from nearly a million camels in 1961 to just approximately 200,000 today. And the fall has been particularly sharp in recent years.

The livestock census conducted by India’s federal government in 2007 showed that there were about 420,000 camels in Rajasthan. By 2012, they had reduced to some 325,000, while in 2019, their population dipped further to a little more than 210,000 – a 35 percent downfall in seven years.

There are multiple reasons for this drop. There is the declining utility of camels for transportation as roads have improved, making motorized vehicles (which are a lot kinder on the bottoms) preferable. There is also a new prohibition on camel slaughter for meat.

(More in this excellent, recent article in Al Jazeera.)

The upshot is that it’s more urgent than ever to find alternative ways of “utilizing” camels if the economics is to support their continued existence. This really shouldn’t be that difficult given what a miraculous creature the dromedary is. For example. camel milk is potentially the new superfood. It is high in essential unsaturated fatty acids and vitamin C. It is better for diabetics than cow milk, since it has a much lower glycemic index. And it is real milk, unlike nut and oat alternatives. It tastes good: rich and flavourful

A recent study conducted by Edith Cowan University in Australia has found that camel milk contains significantly more immune-supporting proteins than cow’s milk (1,143 vs. 851) and lacks the main protein that triggers dairy allergies. What’s more, its bioactive compounds may help fight harmful bacteria, support heart health, and create a healthier gut environment. More here.

In Jaisalmer, my boys had bought three bars of camel milk chocolate to give to friends in Spain as exotic presents, but ended up eating them long before returning to Madrid - they were that yummy. Camel milk ice cream, camel hair blankets, camel bone artifacts: there is a whole world of camel commerce out there. Move over camembert, camelbert could be as tasty and healthier.

Fantasizing about revolutionizing the world’s food industry jolted my memory about the most interesting, and frankly bizarre, factoid I’d been told about camels. It was at a literary festival in Bali, Indonesia, that a young Australian writer I was having a coffee with told me about the million – yes, million! – feral – yes, feral!- camels that apparently roamed the Australian outback. (Which explains why universities Down Under are conducting research on camel milk).

Australia is certainly synonymous with fascinating fauna: kangaroos, echidnas, wombats, platypii (sp?). But camels? Camels are about as Australian as polar bears, and yet in the outback, a 6 million sq km swathe of territory so vast that it is almost twice the entire not inconsiderable size of India, there are so many wild camels wandering about that they need to be culled.

OK, so prepare for the sound of several pieces of the Global Jigsaw fitting in together: South Asia, Australia, and the Canary Islands of Spain, sliding about like tectonic plates until suddenly they interlock at the camel-shaped point where history brought them together.

The first camel to arrive in Australia was imported in 1840 from Tenerife, which at the time had fewer British holidaymakers and more dromedaries (apparently introduced to the islands in the 15th century from north Africa. The idea came from the governor of South Australia who thought camels could be useful in the dry climatic conditions of the north of Adelaide. Half a dozen dromedaries were loaded onto a steamship of the Appoline line in Tenerife, although only one survived the journey, arriving at the harbour of Adelaide on the 12th of October 1840. He was christened, Harry.

Harry made a moderately successful go of it in his new home, although his career ended in ignominy when in 1846 he was involved in an accidental shooting and death of his owner, one Mr John Horrocks.

A two-decade camel-hiatus followed the unfortunate Harry’s Australian debut, but by the 1960s the decks of ships sailing off the coast of north western India – which at the time included modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan- were often heavy with the dromedaries that went on to play a crucial role in outback exploration and settlement.

Between 1870 and 1920 as many as 20,000 camels were imported into Australia along with at least 2,000 handlers, who were called “Ghans” after the Afghans, they often, but not always were. The “Ghans” were mainly Pushtuns, Punjabis, Balochis and Sindhis. came from Punjab, Baluchistan and Sindh.

They ran camel trains, sometimes as with as many as 70 camels, across South and Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Traveling some 20-25 miles a day the camel trains could collectively carry up to 20 tonnes of material on their backs. They accompanied exploratory expeditions and carted wool to ports, barrels of water to drought-hit regions, construction materials, telegraph poles, tea, tobacco and much else, creating crucial lines of supply between isolated settlements.

Even today the luxury train that cuts north to south between Adelaide and Darwin is named The Ghan, in memory of the largely Muslim south Asian cameleers who played such a crucial role in the development of Australia.

By the 1930s, once the railways were firmly established, camels lost their importance as pack carriers. Thousands of them were released into the wild, where over the years they flourished, so much so that they have increasingly come to clash with human outback settlements, destroying water storage tanks and pipelines.

The result is that the government-funded Australian Camel Management periodically culls thousands of animals by shooting at them from helicopters. Between 2009-2013 some 160,000 animals were thus killed.

****

It seems to me that both Australia’s too many camels problem, as well as India’s declining camel challenge can be met with camelbert. I have dreams for a globally successful camel dairy industry : thing dromedary gelato, camel milk body lotion, camel milk health supplements for diabetics etc etc.

Any investors out there amongst the Global Jigsaw community? Spread the word, guys. The camels need us.

That’s all until next week. With love and hopes that you will become a paid subscriber

Xoxo

Pallavi

camels being culled by helicopters wasn’t what I was expecting when I started reading this. A great story as always! Thanks!

Fascinating! Never knew about "The Ghans" and their contribution. I've tried raw camel milk once, it is something of an acquired taste [considering we grew up on processed foods, unsurprisingly]. But camel milk chocolate and cheese? Wow...