The God of All Things

A Catholic Church, in a Muslim-majority area of Indonesia, built in the style of a Tamil Hindu temple.

Hola Golbaljigsawers,

Hope you’ve been well. I just had my booster shot and am hoping very much to be vaccine-free for a while to come.

This newsletter is dedicated to the syncretic. And during my wanderings over the last two decades there have been few embodiments of this spirit that compare to Graha Maria Annai Velangkanni: a Catholic Church, in a Muslim-majority area of Medan, a city in northern Indonesia, built in the style of a Tamil Hindu temple.

It was conceived of, and constructed by, a Jesuit Priest, Father James Bharataputra, who had rushed to greet me as I entered the compound on a visit a few years ago. Bare-footed and dressed in a spotless white habit, Father James, who was then 67-years-old, told me his story with the flair of a practiced raconteur.

Father James Bharataputra. Pic credit: Pallavi Aiyar

Born in 1938, in a town near Madurai in south India, he entered the Jesuit order in 1957 with dreams of serving in a mission abroad. In 1966, his goal was realized when he was sent to work with Tamil communities in Malaysia.

Shortly after his arrival however, the Malaysian government passed an immigration law against foreign missionaries. And so Father James was dispatched to Indonesia. He has remained in the archipelago ever since, spending several years each on the islands of Java, West Papua, and Sumatra.

Father James became a naturalized Indonesian citizen in 1989. The majority of his time over the last three decades has been spent amongst the Tamil diaspora in north Sumatra.

There are around 60,000 people of Indian origin on the island of Sumatra. The majority of these are Tamils who trace their roots in Indonesia to the second half of the 19th century. At the time Sumatra was under Dutch colonial rule and several Dutch-run plantations, in particular the tobacco growing company, Deli Maatschappij, began to bring Tamils from Nagappattina, Madras, and Karrikal, as indentured labourers to work in their estates.

There are few written records that tell their story. In a musty library set up by a former local royal, Tuanku Luckman Sinar, a pamphlet on ‘The Indians of North Sumatra’ written by Sinar himself, was the only literature I could find on the community.

The Dutch contracted Indians, many already working in Malaysia, to construct roads, trenches and dykes, since local workers were thought to be lazy, “their whole nature to revolt against constant application to one particular routine” (Arnold Wright’s 20th Century Impressions of Netherlands India).

The Indian diaspora in North Sumatra also included “free” Indians, mostly Chettiars and Chittis, who worked as traders and moneylenders, as well as Sikhs who found jobs as security guards and dairy farmers.

Tamilians in Sumatra include large numbers of Hindus, Muslims and a minority of Christians. When Father James first moved to Medan in 1972, there were around 700 Tamil Catholics resident in and around the city. They were, he said, an economically backward and deprived group, with barely 10 percent completing secondary school. They lived a ghettoised existence, cut off from the local mainstream.

Father James bought the land that the church currently stands on in 1979 with the aim of persuading Tamil Catholic families to shift there, away from the ghettos that they lived in. But they refused to move, and the land lay fallow for the next couple of decades.

It was only in 2001 that Father James embarked on the construction of the church, following what he called a “miracle”.

The money to build the church had been raised by soliciting donations from the community. Father James had stored these donations in cash at the home of a friend in Medan. But an accidental fire gutted the entire home. The only objects to survive uncharred were the church construction funds, which had been wrapped in plastic, and two copies of the Bible.

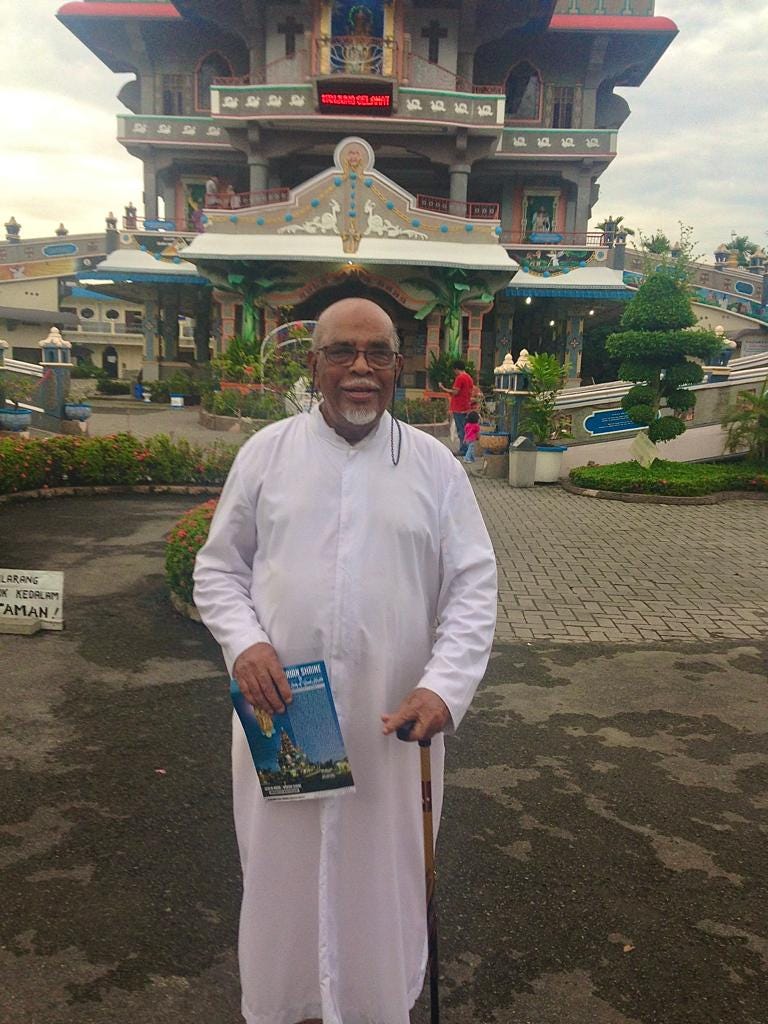

Graha Maria Annai Velangkanni eventually opened its doors in 2005 and since then has gone on to become something of a regional attraction. “The reason I called it graha, or house, rather than a church is because I want it to be open to everyone,” Father James explained. He said that headscarved Muslims, photo-snapping tourists and devout Christians were equally common sights on the grounds.

The church is named after a Tamil village on the Coromandal coast called Velanganni, a major centre of pilgrimage for India’s Catholics. It is here that a shepherd boy is believed to have seen an apparition of Mary and Jesus in the sixteenth century.

While the basilica in the original Velanganni is constructed in the Gothic style, its Sumatran namesake is architecturally unique. The structure consists of a community hall on the ground floor and a space of worship, designed like a conventional church on the first floor. This is reached by walking up a circular ramp. A seven storey, multi-coloured tower, in the style of a gopuram (the ornate entrance towers that are common at the entrance of Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu) tops the building, triangulated by domes that Father James said were inspired by Mughal architecture.

Me with Father James Bharataputra standing in front of Graha Maria Annai Velangkanni

Within the fan-cooled church the hush was broken by the keening of a devotee who rocked back and forth at the foot of a statue of Jesus. The high walls had quotations from the bible painted on in four languages: Indonesian, Tamil, English and Chinese. (Medan also has a substantial Chinese origin population).

As the sun began to set, Father James retired to a modest chapel to the side of the main structure where he led mass. The service was conducted in Indonesian, the Tamil Christian diaspora having largely lost the ability to speak Tamil over the decades. The congregation was moreover, a mixed one, with several local Sumatrans in attendance.

As Father James led them in prayer, loudspeakers from the neighbouring mosque began to blare out the azaan, momentarily drowning out the Jesuit’s words. But the call and response of the mass proceeded without interruption.

Later, the lights were turned on and the church’s gopuram set ablaze in coloured fairy lights, dazzling against the night sky. As I drove away, I saw a young Chinese woman in skintight jeans snapping a selfie in front of the structure.

****

Hope you enjoyed this snapshot of what a less sharply divided world could look like. If you did, please consider becoming a paid subscriber of The Global Jigasw. It’s a small contribution that you can make to help spread the word about how much more unites us globally than we generally believe. Thanks and keep fighting the good fight.

Hasta proxima semana,

Pallavi