Dear Global Jigsaw,

Does it make you happy?

I have always tended to be skeptical of this, in-vogue, yardstick by which to adjudicate life’s big decisions. So much of what gives a life meaning- parenthood, health, discipline, friendships, learning a new skill- does not equate unalloyed happiness. It is difficult things that reward one with the most joy. “Happiness” is too easy to be consequential – like empty calories, a bag of potato chips.

Perhaps it is semantic. What I call joy, you call happiness. But for me the distinguishing fundamental is that joy is long-term, requires work and involves some level of gratitude, while “happiness” is giggles and bubbles- ephemeral. It’s a new pair of shoes, or 100 likes for your Instagram photo. Joy, conversely, is the day your child cooks you a meal – after YEARS of your cooking her one. Or the day you can move your shoulder again after a mastectomy. It’s sitting with an ageing aunt and listening to her recollections. It’s taking your dog for a long walk.

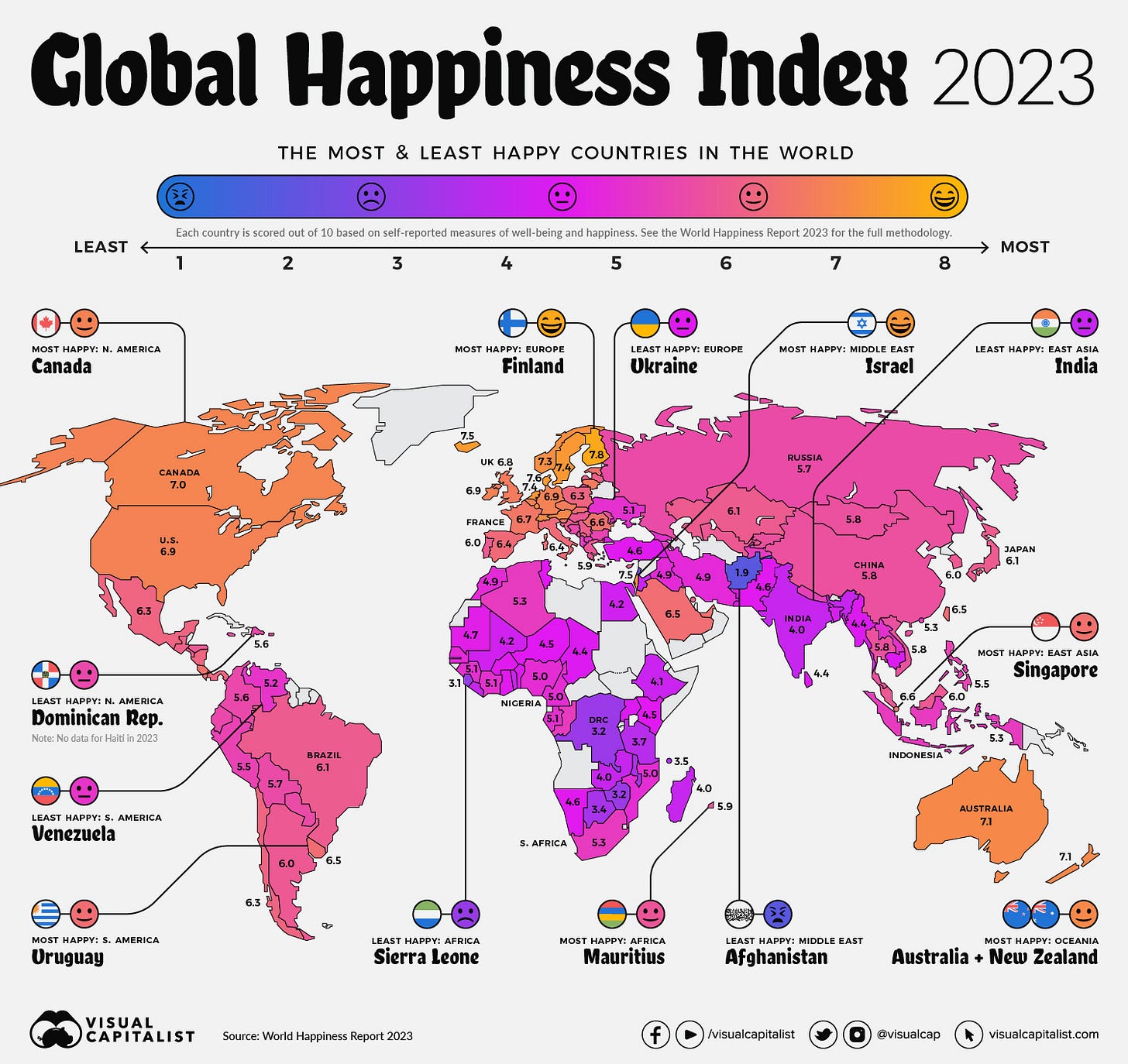

All this is by way of prelude to today’s post, which is about Happiness Indexes. I usually find these vexing, given that it is inevitably the Nordic countries with their foreboding skies, biting winds, and high alcohol consumption, that come out on top.

This just feels wrong. Why? Here’s an excerpt from my Europe book, New Old World, as explanation. It’s about my first visit to Denmark in 2009.

“As my plane swooped down towards the Copenhagen airport, a forest of rotor-headed offshore windmills reared up, their slender necks glinting in the mid-morning sun (which was pretty much the only kind of sun that Denmark knew in December)…

The country was supposed to house the world’s happiest people, and often topped the kinds of charts that tried to quantify such things. Minimum wage was $20 an hour. The government paid for college education. Free healthcare and outstanding parental support contributed to the general wellbeing of the citizens. It felt implausible that countries like India and China with their smog, stench and sores, even shared the same planet with this utopia.

On the way to the hotel, I looked out of the taxicab at all the intimidatingly trendy people in rimless glasses walking about. I was stabbed by envy every time I spotted a young, blonde mother pushing her designer-looking baby about in the lofty heights of a Stokke pram. Since having had a baby myself, I noticed things like strollers. Nothing evoked greater jealousy than the sight of a Scandinavian-made Stokke stroller, the Rolls Royce of prams.

I imagined myself sashaying down the streets of Copenhagen in stilettos with an equally well-groomed Ishaan ensconced in a Stokke, ne’er a smear of banana puree in sight. But was rudely awoken from this reverie by the angry tinkling of a passing bicyclist, whom I barely avoided getting mowed down by.

The taxi had spilled me onto the bicycle lane that ran along the pavement by, and this was obviously somewhere one did not dawdle in Denmark, if one valued life. Like other aspects of Danish society, bike etiquette was designed to operate like a well-oiled machine. Disrupt the order by oafishly standing around for a moment too long in the bicycle lane and you instantly became the worst thing that had happened to a Danish bicyclist in a long while, causing all that trust and tolerance and acceptance of high taxes to collapse like a house of sand.

That night I had dinner with the friend of a cousin, I’d met in India a few years ago. She was possibly the most miserable person ever, putting paid to the orthodoxy of happy, content Danes. She spent all evening moaning about how expensive everything was in Denmark and how she’d kill to be able to afford servants like the middle classes in India. Don’t get taken in by appearances she warned. All those slick looking moms wheeling Stokke prams were crying on the inside, exhausted by the daily drudgery of shopping and cleaning and cooking and working. When I made noises about getting a taxi to return to the hotel, she turned solemn. Be careful with the taxi drivers she said, her pale blue eyes darkening. Particularly avoid the ones that look like Pakistanis.”

Last week, I read of a new five-year survey based on a sample of over 200,000 people in 22 countries, on all continents except Antarctica. Conducted by a triumvirate of social scientists: Brendan Case, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Byron Johnson, the results of this study are grist to the mill for the idea that the standard World Happiness Report misses something crucial about the thing it purports to measure: happiness.

This Report always reflects the idea that rich countries are happy and poor ones, sad.

In a guest post for the New York Times, Case et al state:

“These rankings reinforce a key supposition of our globalized political and economic order: Poor countries are unhappy because they are poor, and wealth is a critical precondition for individual and societal flourishing. The International Monetary Fund encourages trade and economic growth on the theory that happiness increases with material prosperity. The aim for poor nations on this metric of happiness is to “get to Denmark.”

The World Happiness Report survey only asks respondents a single question: to imagine life as an 11-rung ladder where the top step is the best possible life, and the bottom - the worst. People are then asked to place their life on one of the rungs. But happiness is more complex than the information revealed by this single parameter. You might live in a polluted city, but still have a strong sense that life is meaningful or be financially insecure, but still have deeply fulfilling relationships with family and friends.

The new study, therefore, focuses on a more composite index called “flourishing.” It includes questions on diverse spheres of well-being including not only material prosperity and health, but also meaning, character and social relationships. Once this wider definition of Happiness is operationalized, Sweden suddenly falls from top place to 13th highest, considerably lower than Indonesia, the Philippines and even Nigeria.

In fact, the overall national composite flourishing score decreased slightly as G.D.P. per capita rises. “Most of the developed countries in the study reported less meaning, fewer and less satisfying relationships and communities, and fewer positive emotions than did their poorer counterparts. Most of the countries that reported high overall composite flourishing may not have been rich in economic terms, but they tended to be rich in friendships, marriages and community involvement — especially involvement in religious communities.”

In the study (which will be published on Wednesday, May 7) Japan scored amongst the lowest on the composite flourishing index, while Indonesia, topped the charts.

Indonesia is often compared unfavorably with Japan in discussions of international development, cited as an example of the so-called middle-income trap, in which GDP plateaus before reaching high-income levels. But a focus on “composite flourishing,” suggests that economic growth tells only part of the story.

Indonesia and Japan are countries that I have lived in for four years each. Impressionistically, there is little competition between the two on happiness. Indonesians smoked and ate fried bananas smothered in chocolate and cheese, but they laughed often and easily. Shooting the breeze with friends was a national past time. Most people maintained an admirable emotional equilibrium even in the face of Jakarta’s notorious, daily traffic gridlock. Gossip and prayer punctuated lives.

The Japanese by contrast, wore emotional corsets. Many were overworked, stressed and depressed. Japan’s suicide rates were high. On average, 17.5 per 1,00,000 people killed themselves in Japan, compared to 1.2 in Indonesia. The first story that I reported from Tokyo was on karoshi, a neologism that means death by overwork.

The complexity of “happiness” means it is difficult to pin down on the basis of objective criteria. Attitude probably has much to do with something that is after all a subjective mood. The children of slums in India playing joyously in the filth are almost a cliché. And it does deserve some attention.

A guest post in The Global Jigsaw took a stab at unpacking what the author, Priya Malhotra called “the paradox of happiness” by suggesting that happiness is a function of expectations. When you expect less, you are more satisfied with what you have. It’s enough.

Is happiness then the ability to be content with the cards dealt to you? I suspect there is truth in this. Money can cushion stress and help one enjoy the fine things in life. But it does not temper greed, only feeds it, often leading to more stress and insatiable cravings. As the Beatles put it, “Money can’t buy me love.” And GDP seems less able to buy happiness than we may have been conditioned to assume.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments.

And please do upgrade to a paid subscription if you can, to support the labour behind this newsletter. I get joy from the discipline of writing and the crafting of ideas and sentences, but there is no denying that while money is not the prime motivator of this project, a modest sprinkling keeps the conditions propitious for its longevity.

Much love to all,

Hasta la proxima semana,

Pallavi

After his first visit to India my thesis advisor visited India (in late 70s), he observed that Indians seem to be genuinly happy and contended. I disagreed with him, but now I feel he was more on the mark.

loved this Pallavi. I agree. Time to revise these so called parameters and hyped happiness markers. Maybe we should begin with defining the momentary/ situational nature of happiness versus the nature of joy..that one needs to dig deep for.