There is a lot of righteous rage in the world, although “righteous” is a shapeshifting shadow of an adjective. From Brussels to Bombay – oops I mean, Mumbai, statues have been toppled, cities renamed, books banned and words rewrought. Much of this erasing and refashioning is done in the name of righting wrongs, of setting the record straight, of telling the “truth.”

The targets of revision have usually been less than salubrious: symbols of prejudice running the gamut from race to religion. A statue of Belgium’s King Leopold, the uber nasty colonialist of the Congo who ordered the hands of his enslaved rubber-tappers be cut off when they failed to meet quotas, was removed from a public square in Antwerp last year.

In the UK and US, the statues of a smorgasbord of white supremacist, slave-owning nasties, aka the past luminaries that the contemporary “West” owes its present global preeminence to, have been attacked.

Moving East to my motherland India, the renaming of cities and streets has become so common that I’ve begun to experience cartographical aporia even in my hometown of Delhi. The Indian capital receives some 300 requests every year to rename roads and parks after deities, local politicians, army personnel and even Bollywood actors. Trying to make my way in the city after a gap of two years, as I did in December last year, felt as though the authorities do little but authorize these changes.

Renaming thoroughfares is not a new phenomenon. Many roads in Delhi were rechristened long before I was born. These were usually avenues once named after British colonialists, given fresh monikers as part of the decolonization process.

And so, Curzon road (George Nathaniel Curzon was Viceroy of India from 1899–1905) became Kasturba Gandhi Marg (after Mahatma Gandhi’s wife). Hardinge Avenue (Charles Hardinge was Viceroy of India from 1910 to 1916) became Tilak Marg (Bal Gangadhar Tilak was an influential leader of India’s independence movement). And Keeling Road (Hugh Keeling was head of the Public Works Department in the early part of the 20th century), was renamed Tolstoy Marg, in honour of the Russian literary legend.

However, in recent years, the drive to rename not just roads, but entire cities has focused less on decolonizing these spaces, than de-Islamifying them. India’s current rulers are expanding the cast of characters to be erased back in history to include the luminaries of the Mughal empire that dates to 1526. For India’s Muslims this is clear messaging: you are foreign, you are “other,” you are cancelled.

Delhi was the seat of the Mughal empire for centuries. Its Islamic heritage is written into its bones. The tombs and gardens of its erstwhile Muslim rulers are the arteries of its life blood. Its language is a phonetic confluence of the cultural amalgamation that resulted from the Hindu-Muslim encounter.

The names of things give them shape. And so, to find the city, and the country beyond, increasingly re-labelled is akin to having swathes of the geography of my childhood erased. It’s like I can’t trust my own memory anymore. My personal history has become unreliable.

The funny thing about the past is how it is not past at all, but present. History is a contemporary protagonist, defining the present as much as it is defined in turn by the present. What went and what goes dance a tango, feeding off the energy of each other, taking turns to lead, encouraging a pirouette here and a sidestep there.

So how should we proceed? Take down the statues? Or keep them standing? Rename the roads? Or leave them be? How do we best deal with the inevitable partiality of “truth?” With the slipperiness of History?

Dear reader, you tell me. The comments section awaits your responses.

As for me, I believe the only path forward is to acknowledge clashing perspectives. We are all good and bad and plentifully grey in between. How about we leave the statues up and contextualize them to get at the ways in which their symbolism has changed over time. To help understand, in other words, how “history” works. How it is not a static fact, but something that is created by the implicit norms of the beholder.

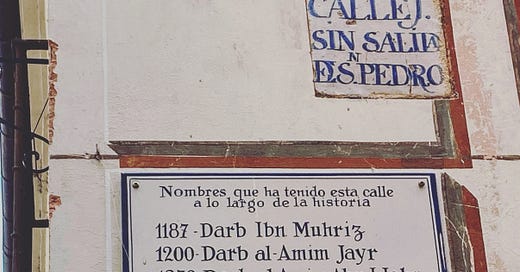

As for roads, if you have to rename them, how about plaques that allude to the other names that went before? I found a great example of this in the city of Toledo, near Madrid.

Street in Toledo. Pic credit: Pallavi Aiyar

Instead of just walking indifferently through yet another street named after San Pedro (Saint Peter), a sign like this sings the storied past of the city. It’s difficult as a visitor to see the street in the same way once you’ve read it.

I also had the opportunity to wander around a small museum in Los Angeles recently. Called the Wende museum, it’s housed in a former atomic bomb shelter built in 1949 in anticipation of a World War III Soviet air strike.

Today, it is home to a quirky, but extensive, collection of cold war artifacts and memorabilia, from Lenin busts to typewriters.

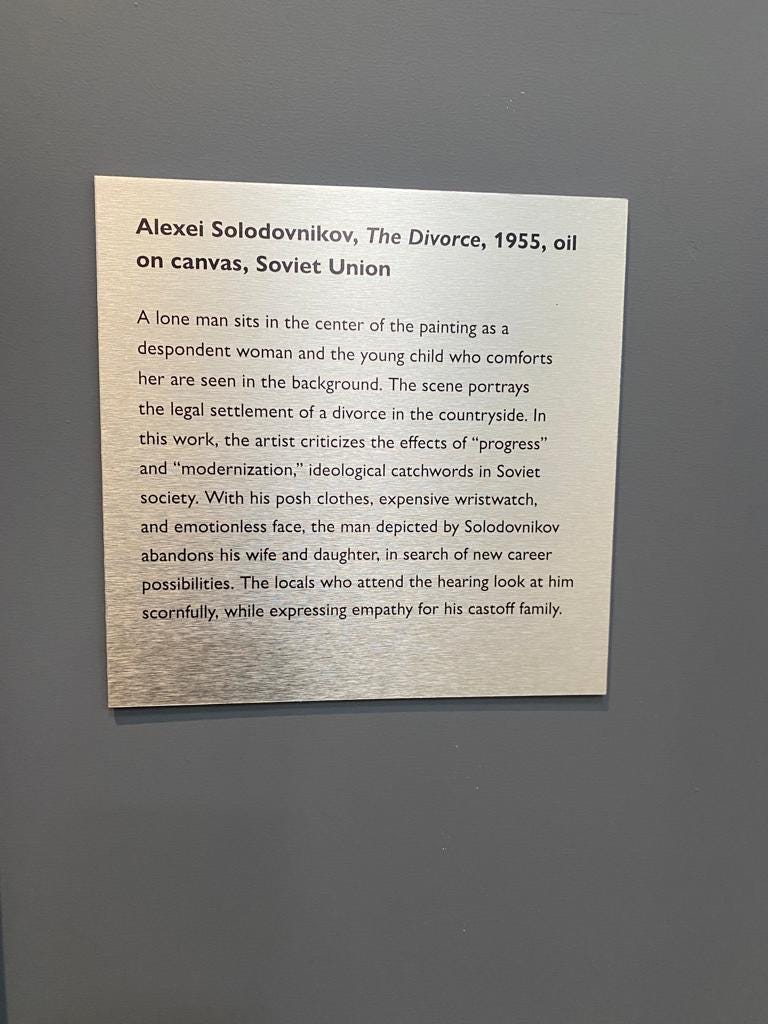

Exhibit at the Wende Museum. Pic credit: Pallavi Aiyar

The exhibition I visited was titled Questionable History and it pretty much attempted to do what the title suggests. Here is a description from the catalogue:

“This exhibition explores the boundaries and grey zones between objective facts and subjective interpretations and invites viewers to ask critical questions about reality and fiction. Is history a story we tell? Do facts speak for themselves? ..”

I loved the section titled, In Search of Truth, which displayed artwork alongside contrasting interpretations of it.

The Divorce 1955 by Alexei Solodovnikov, Soviet Union. Pic Credit: Pallavi Aiyar

In another corner was the “What Do We Know,” installation, that emphasized what it is that we do not know about the works on display.

****

I was instantly in love, not knowing things being my specialty, and knowing that I don’t know things, my badge of honour.

I think there is a good case to be made for Wendifying statues, museums, indeed anything where “history” is showcased, because the only way to understand the truth is to understand how we know so little of it.

OK, my lovelies. That’s it for this week.

May I make my weekly request for you to consider becoming a paid subscriber? I feel like a beggar going around with a coin box. Sorry! But one must as one must, so do press this button and follow the instructions.

And as always, share share share.

Love and light,

Pallavi

I fully endorse the way our friends in Toledo have found to innovate while respecting the past: time changes viewpoints, but its important to leave a record of change. The San Pedro street plaque in Toedo shows the way

I love this statement, especially in the context above: "I was instantly in love, not knowing things being my specialty, and knowing that I don’t know things, my badge of honour."