Greetings my Global Jigsaw family,

A few months ago, I interviewed the British journalist and historian, Giles Tremlett, at the Secret Kingdoms bookstore in Madrid, about his recent work on the International Brigades that fought in the Spanish Civil War. I must admit that prior to reading his book, I had only the most tenuous grasp of what had gone down. More a feeling shrouded in a sense of romance à la Ernest Hemingway, than any hard facts. Although I did vaguely recall a paragraph about the International Brigades from a middle school history textbook.

The Spain’s Civil War lasted for nearly three years (July 1936-March 1939) and claimed at least one and a half million lives. But this tragedy became a rallying cry for many in that generation.

What I do remember from my textbook is that even the dryly written, lone paragraph, about the International Brigades had me misty eyed, in the same way that reading Tolkien’s, The Lord of the Rings, did. It was the idea of diverse peoples putting aside their differences to fight the good fight; to find common cause in their humanity. Hence, The Global Jigsaw.

And just as the Elves, Hobbits, Men, Dwarves, and even the Eagles eventually gathered as one, to defeat Sauron’s forces in Mordor, so the International Brigades seemed to me, to be proof that however flawed human might be, there was hope for us in our ability to stand up for a cause that was larger than our individual predilections.

Over 35,000 volunteers from sixty-one countries fought in Spain against Franco and his Nazi supporters. Now, we are talking about a Civil War and there is still lack of a consensus within Spain about viewing the war in a binary good-bad fashion. But this post is not about discussing the rights and wrongs of the Civil War but of a small corner of the canvas.

Most international volunteers came from nations that were themselves colonizers. The “good fight” was defined as the one against fascism, but colonialism remained un-interrogated. Despite this there were a number of colonial subjects who also joined the Brigades. Jawaharlal Nehru, who would go on to become independent India’s first prime minister, visited Spain in 1938 as a show of solidarity, and Indians in London organized fund-raisers and an ambulance for the International Brigades.

Jawaharlal Nehru in Spain during the Civil War, with his daughter Indira (l), future prime minister of India, and Catalan President Lluís Companys (r).

In total there are six Indians who are known to have made their way to Spain to fight against Franco as part of the International Brigades. These included Mulk Raj Anand, who would become a famous author; three doctors -Atal Menhanlal, Ayub Ahmed Khan Naqshbandi and Manuel Pinto - and a student named Ramasamy Veerapan.

This guest post is about the sixth, Gopal Mukund Huddar, a founding member of the Hindu nationalist organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Huddar went on to become a Marxist and thence a brigader in the Spanish Civil War.

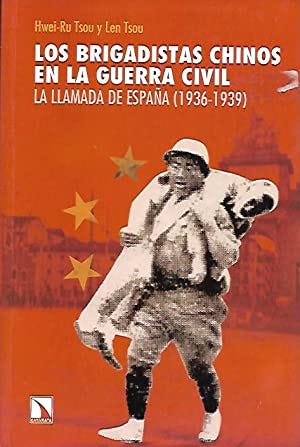

The writers, Nancy Tsou and Len Tsou, are authors of the book, Los Brigadistas Chinos en la Guerra Civil: La llamada de España. Their research has mostly focused on the Chinese who found in the Brigades, but they also uncovered some fascinating details about Huddar. I have been in touch with them over email and they graciously agreed for me to share this piece on The Global Jigsaw.

I hope you enjoy this post and please do share it. As always, I must ask you to become a paid subscriber if you are able. Its imperative for the Global Jigsaw’s continuing life, given that I have had to cut back on other paid work. Thank you :-)

****

It was November 12, 1938. A public meeting, organized by the Indian Swaraj League, a political organization demanding India’s self-rule, drew a large audience of spectators, both Indians and British, to Essex Hall along the north bank of the River Thames. Speakers from various Indian and British organizations had gathered there to welcome an “Indian member of the International Brigades who fought for the Republican Government in Spain, and who recently returned to England after being a prisoner of Franco.”

The guest of honor was Gopal Mukund Huddar. On the invitation card, Huddar was highlighted as the “only” Indian member of the International Brigades. In fact, he was one of several Indian volunteers, including the famous Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand, three Indian doctors, Dr. Menhanlal Atal, Dr. Ayub Ahmed Khan and Dr. Manuel Rocha Pinto, and one Indian student Ramasamy Veerapan.

Among them, Huddar was the only Indian prisoner-of-war in Franco’s prison.

Gopal Mukund Huddar in 1936 (Courtesy of Shailendra Vaidya)

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, Huddar was studying in England. Together with some British volunteers, he arrived in Spain on October 17, 1937. At the headquarters of the International Brigades in Albacete, he was assigned to be a member of the Saklatvala Battalion. This was a British Battalion named after Shapurji Saklatvala, a prominent Indian Communist in England who had died in 1936.

To support the Spanish Republic, his 18-year-old daughter Sehri Saklatvala arranged an event “FOR SPAIN, India Evening” in London in March 1937, which was organized by the Spain-India Committee. One of the speakers was Indira Nehru, daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, future first Prime Minister of India.

At the time, Nehru was very concerned about the fascist menace in Spain. He said, “I wish, and many of you will wish with me, that we could give some effective assistance to our comrades in Spain, something more than sympathy, however, deeply felt.”

Nehru’s call was answered by the Indians living in Britain. The India League, a Britain-based organization committed to campaigning for full independence for India, founded the “Indian Committee for Food For Spain.” In the fall of 1937, the Spain-India Aid Committee donated an ambulance to “the courageous Spanish democrats.”

A year later, in June 1938, Nehru himself traveled to Spain. He paid visits to General Enrique Lister at Lister’s headquarters and also to Catalan president Lluís Companys. He was so impressed that later he wrote, “There was light there, the light of courage and determination and of doing something worthwhile.”

Later, on July 17, 1938, at the second anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, Nehru addressed a crowd of 5,000 in Trafalgar Square in London at a rally in aid of Republican Spain.

It was in this same spirit that Huddar joined the International Brigades in 1937. To shield his Indian lineage, Huddar changed his name to “John Smith”, a common English name. There were at least four men named “John Smith” in the Brigades. To differentiate him from the other “Smiths,” his comrades added “Irakian” after his name. This was probably because he indicated that he knew the Iraqi language when he filled out forms in Spain. Some of his comrades even thought he was born in Iraq. However, relatives of Huddar said that he was born in India and never set foot in Iraq. In fact, they never heard him speak the Iraqi language. His daughter believed that this was her father’s tactic to camouflage his true identity.

On February 11, 1938, Huddar went to Tarazona to receive non-commissioned officer training and then served as an instructor in the Infantry. But on April 3, Huddar disappeared in the battle of Gandesa, taken prisoner by Franco’s army and imprisoned with other brigaders in San Pedro de Cardeña.

One of his jail mates was Carl Geiser, a brigader from the U.S., who had vivid memories of “John Smith” in the jail. Geiser identified him as Nagfeur Hudar from India. In his book Prisoners of the Good Fight, Geiser wrote of Huddar having given lectures on “the struggle for independence from Britain of the people of India under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.”

In another lecture, John Smith described himself as having some of the skills developed by yogis and fakirs. He went on to demonstrate his skills of palm reading. After studying Geiser’s palm, he said, “You have one brother and four sisters.” Geiser was flabbergasted because he had hit it exactly. John Smith studied his palm further and told Geiser two more pieces of news, one good and one bad. The good news was “you will live a long time,” whereas the bad news was “Carl, in your old age you will have an affliction. Exactly what it will be I do not know.”

Hearing this news, Geiser was very happy, since this meant that he would be able to get out of Franco’s jail alive. The prediction came true. When Geiser was put in front of firing squad, a notice of prisoner exchange came in time to spare his life. Geiser in his sixties was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. As forecasted by John Smith, Geiser lived to the ripe old age of 99.

Geiser was released from Franco’s jail, but who would rescue Huddar, a lone Indian prisoner? For Huddar, chances of being freed were very slim. But he had a stroke of good luck.

At that time, the British government was negotiating with Franco for the release of British prisoners. As a result, a team was dispatched by the British government, among them a retired colonel, whose son was also held prisoner. When the colonel visited his son at the prison, he encountered a peculiar prisoner, who bore the name “John Smith” but looked Indian. John Smith revealed to the colonel that he was actually an Indian from Nagpur and his real name was Gopal Mukund Huddar.

It turned out that the colonel had commanded a regiment at Kamptee cantonment near Nagpur before his retirement. Nostalgic memories made him sympathetic to Huddar. He included Huddar’s name along with other British POWs, enabling his freedom.

Huddar was born on June 17, 1902 to a Brahmin family in Central India. At the age of four he was adopted by a Brahmin widow named Udhoji who lived in the city of Nagpur. Later, during days as a student, Huddar became opposed to the education policy enforced by the colonial government.

After receiving his BA degree from Morris College in India, he joined a newly founded secret society named the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh (RSS): a Hindu organization. The following year, the young Huddar, 23, became its General Secretary.

However, the RSS was only interested in Hindu civilization, and could not satisfy Huddar’s revolutionary fervor. He was more interested in taking action to liberate India from British rule. He pursued his clandestine revolutionary activities independent of the RSS. Along with a group of friends he stole weapons and ammunition for which he was caught, sentenced and imprisoned by the British Government in 1931. By the time he was released, in 1935, from jail, he’d been sidelined from the core group of the RSS.

In 1936, with the encouragement and financial support of his friends, and a philanthropist from Nagpur, Huddar went to England to study journalism, where he witnessed the powerful international solidarity for the Spanish people’s fight against fascism. The India League collaborated with the Communist Party of Great Britain and other Left organizations to hold meetings and organize marches in support of the Spanish Republic.

Huddar began attending these meetings and rallies. His mind further shifted away from the RSS’s Hindu nationalism. After much reflection, he realized the paradox of being a good nationalist without also being an internationalist. This logical conclusion led him to join the International Brigades in Spain.

After being freed from Franco’s prison, Huddar went to London to a hero’s welcome. A month later, he returned to Bombay, where many union workers gathered at the wharf to greet him with garlands. Several Bombay Unions and the Bombay Congress Socialist Party held public meetings in his honor. Amid shouts of “Long live Spanish Democracy,” Huddar rose to speak, in fluent Marathi. His speech fired up the crowd:

“The honour you have done me is really the honour to the cause of democracy and freedom which Spanish workers and peasants are defending with their lives…. The fight for democracy is in India, just as it is in Spain. The very same British Imperialism which helps Franco and Mussolini in their attempt to destroy Spain is holding us down. We have to fight against it. We have to build the unity of the workers, peasants and the middle classes just as the Spanish people have done.”

Huddar conveyed similar thoughts in an article “Spain and Ourselves,” suggesting that “Democracy extinguished in Spain, would entail not only the victory of barbarism in Western Europe, but the same weapons will be used for crushing the movement for our own Independence. People determined to gain their own freedom cannot allow the freedom of other people being submerged through the organized butchery of Fascism.”

His experience in the International Brigades and its underlying Marxist philosophy had made a huge impact on him. In 1940, he joined the Communist Party of India (CPI) and began to work for the cause of peasants and laborers in the countryside around Nagpur headquarters.

****

What struck me while reading this history was how naive many Indian nationalists seem to have been in assuming synchronicity between the anti-fascist and the anti-colonial causes. What do you think?

Do post comments and as always, share, share, share.

Love and light.

Pallavi

Your writeups are a feast- good writing, information and a fresh perspective all rolled into one.

One thing that has struck me in such stories is how global many Indians were during the early part of the 20th century. They would silently slip away and find themselves in the unlikeliest parts of the globe supporting good causes or to make a living, or simply to esacpe their colonial masters.

And most times England would be their gateway. England was a sort of in-law's home to them easy to reach in the name of study only to be distracted by much larger causes.

I lived in Spain during the past several years of Franco’s regime. His shadow blanketed the country with ignorance and oppression. You had to guard your opinions about politics unless you were absolutely sure you were speaking to people of like mind. Censorship was rampant and progress was a swear word. Very interesting and nuanced story. Thank you.