Hello Clan of the Global Jigsaw,

I’m pretty sure its been a tough week for most of you between the war in Ukraine and elections in U.P. in India.

One thing I’ve realised is that I am the anti-guru. Have totally lost faith in my ability to know anything. I’d predicted Brexit would never happen, Trump would never be elected, the Covid pandemic would blow over in a few weeks and that Putin wouldn't actually invade Ukraine. Please don’t ever believe me on this sort of crystal ball gazing.

One thing I do know with certainty, however, is how lonely it is to be an Indian foreign correspondent and the consequences of this solitary state. On to this week’s post - but before which may I ask you to become a paid subscriber of this newsletter? It takes time, effort and skill to produce and I hope you think its worth paying a small monthly fee for.

If you are unable to pay for whatever reason, it remains free to access, but do share with friends and family to spread the word.

The job of the Indian foreign correspondent is a lonely one. Over the last two decades I have reported from Beijing, Brussels, Jakarta and Tokyo. In the latter three cities I was the only Indian journalist in town. In China, I was one among three.

The reason for this solitary state of affairs is complex. Travel, research and reportage in foreign lands needs the kind of financial commitment that Indian media organizations either lack or lack the appetite for. Even as the Indian state struts and frets its hour upon the global stage full of sound and fury, most Indians remain deeply parochial. Foreign news in India must contend with outsized competition from Bollywood, cricket, and domestic electoral machinations.

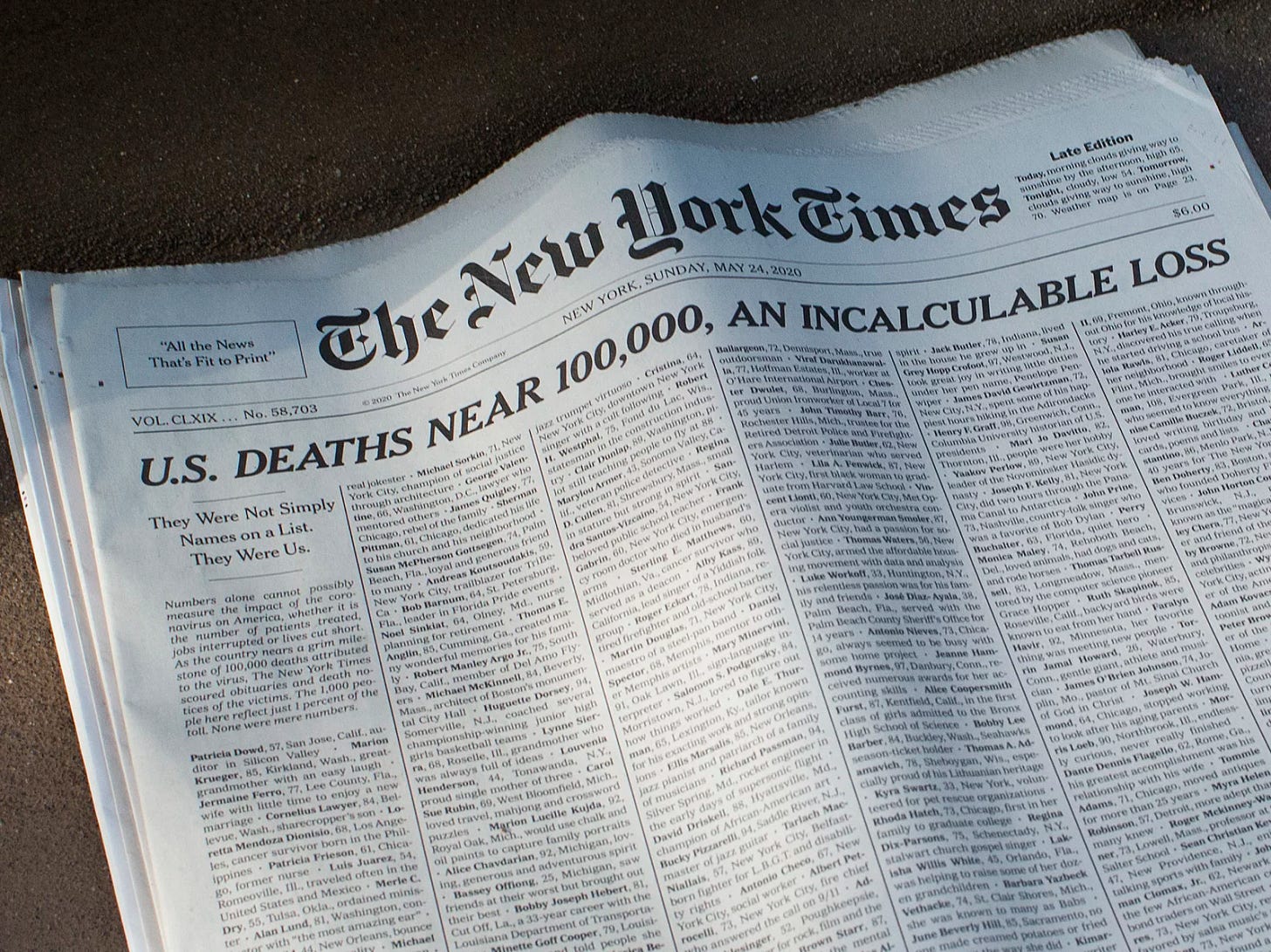

All of which goes some way in explaining why the wide-eyed questions I get from my compatriots about other countries, leave me with the impression that they believe themselves to be nationals of the New York Times, rather than India. Their implicit norm, when it comes to analyzing the foreign, is bewilderingly disconnected from their Indian quotidian. Let me explain with a few examples.

Airenfreude

On visits back to Delhi during the years I was reporting from China in the run up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, I was confounded by the schadenfreude I encountered regarding air pollution. At social gatherings it was common for random acquaintances to delightedly commiserate with me about having to put up with the Chinese capital’s terrible air.

“It’s so bad there, no? People even have to wear masks outside! Tch! Tch!”

“Oh, the poor kids! Imagine having air purifiers in the classroom. So sad.”

Once my older son was born, I was even asked if I’d consider moving back home out of concern for my baby’s health. “Because Delhi’s air is so salubrious?” I wanted to reply, but I was aware that this would be sarcasm off a duck’s back. It was as though my interlocuters didn’t breathe or just look outside their windows.

They must have, but the New York Times had not cottoned on to India’s air pollution problem yet, while Beijing had become the international poster boy for bad air. Consequently, this was how the Indians I spoke to perceived the world to be. China was associated with the environmental degradation that the western media framed their stories about it around, while India’s own air catastrophe had to wait for external acknowledgment before it could become visible.

Feeling bad for Japanese women

Then came my four-year stint in Tokyo from 2016 on. Japan generates considerable interest in elite Indian circles because of the country’s cultural appeal as a travel destination. Society ladies are in rapture at the thought of sakura in bloom and Japanese whisky has acquired cult status. But one question I was repeatedly asked was about the lowly status of women in Japanese society, accompanied by tut tutting reminiscent of comments about Beijing’s air a decade earlier.

My interlocuters you see, were all up to date with the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap Report, in which Japan regularly places below other advanced economies. Hence the seeming absurdity of Indians feeling bad for Japanese women.

Yes, India had had a woman Prime Minister. Yes, some of India’s top executives and entrepreneurs were women. But the fact is, that unlike in most Indian cities, women in Japan could usually go out for a walk.

In Japan, women inhabited public spaces with confidence. They dressed as they liked. They drank what they like. They tended to be more sexually liberated than the global norm. Even the idea that Japanese women stayed at home, unwelcome by the workforce needed to be tempered. In fact, over 76 percent of Japan’s adult women work outside the home (albeit often in part time or lower paid jobs). The equivalent figure for India is an abysmal 20 percent and declining.

****

The spatiotemporal dysmorphia of the Republic of the New York Times in India

How does one make sense of this phenomenon? To begin with, many of these reactions are characteristic of the rarified demographic that already lives in a nation-within-a-nation, cocooned from the larger geographical entity they inhabit by class, caste and access to the New York Times.

It’s ironic that in cities like New York and London, Indian immigrants cluster to form Little Indias, while in India itself, elite Indians clump to create Little New Yorks/Londons. These latter ghettos aren’t populated by immigrants, but by locals who act like expats. People whose world views and sense of norms suffer from spatiotemporal dysmorphia. Their physical bodies are in India, but they understand the wider world from the vantage point of the English-speaking capitals of the West.

Same fact, different conclusions

But another reason beyond the reality distorting lenses of privilege, is the egregious lack of Indian foreign correspondents. And so, we return to the beginning of this column. An Indian and a “westerner” in a third country often interpret the same facts in completely different ways.

The traffic in Beijing for someone from Delhi, for example, comes across as remarkably orderly. For someone from Germany, on the other hand, it is remarkably chaotic. Same “fact,” but polar opposite observations. Clearly, for Indians to learn about the world through western lenses is to get a cockeyed, partial sense of it.

Moreover, foreign correspondents don’t just inform their audience about other parts of the world, but in doing so they also hold up a mirror to their home nations, as provocations for thought and action.

Just as travel abroad has the counterintuitive effect of helping travelers wake up to themselves - of seeing themselves more clearly, because of the comparative framework they now have – so the work of a foreign correspondent assists at a more general, nation-wide level, to help a country both understand itself better, as well as its place within the wider context.

Catch-22

But in India, it’s a Catch-22 situation. Indians learn little about foreign countries and whatever slips into their consciousness is mainly through the work of western journalists. Understandably, they develop little true interest in the world beyond. But that lack of interest is then used as justification by Indian media editors to give short shrift to international coverage, which in its turn feeds that indifference, closing the unfortunate loop.

Desperately seeking an Indian foreign correspondent in Ukraine

A current example of the consequences of this lacuna is the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine. For India it throws up a range of strategic and ideological dilemmas that require serious thinking through. What kind of an actor does India want to be on the global stage? What does India’s reaction to the war say about its sense of self? What water does its vaunted principle of national sovereignty and non-interference in the sovereign affairs of other countries hold, in the face of the unwillingness to condemn a blatant violation of that principle?

There is more than one possible answer to these questions. But the lack of a broad public discourse on them is glaring. Until the actual tanks started rolling into Ukraine, Indian media was fixated on whether girls in hijabs could attend school. In the meantime, events were fundamentally reshaping the global strategic landscape and India’s place in it.

*****

That’s all for this week. If you enjoyed this piece please do comment and share.

Hasta la proxima semana,

Pallavi

PS: This piece was first published in Open Magazine

Dear Pallavi,

the "Marwari" or the "Lucchesi" model?

I'm reading on the origins of Swiss wealth: by the end of the XVIth century, the country was one of the major European producers of silk, cotton, and the like. By the end of the Napoleonic wars, it was first among textile machines. Why?

1555 the protestant Locarnesi were expelled from their home town. In about 1570, it was the time of the Protestant Lucchesi - Lucca was a center silk production. They fled to poor and narrow-minded Switzerland and, thanks to their *entrepreneurial* skills, transformed the country.

Like the Marwaris or Parsees, these proto-capitalists used their international networks. Unlike them, they had no place to go back to, so they transformed first trade, then production, wherever they managed to put down roots. No nostalgia, just desire to succeed and a fresh eye for unused resources and opportunities. The local elites saw it and got into the act - their price for allowing the newcomers in.

Protestantism helped - in unexpected ways. Reformer Zwingli forbade soldiering in foreign lands - a valid income for strapping lads in excess to poor agriculture. Now at home with nothing to eat, they willingly took up weaving and the ladies spinning for subsistence wages. The Lucchesi and Locarnesi provided the capital to fund the purchase of raw material, transformation, and export. Wealth spread across parts of the country.

Integration in the new country and mongrelisation is the key. On both sides.

Thanks Pallavi for this insightful column. It still leaves me wondering how many readers does The New York Times have in India... and whether you perhaps happen to know all of them. After all, I'm impressed by the quality of your friends and acquaintances. I can assure you that I could not write something like "My interlocuters you see, were all up to date with the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap Report." The other side of this coin, of course, is that foreign papers have had remarkably little success in setting up shop in India. I still remember the FT's unsuccessful effort a decade ago.. (https://www.hindustantimes.com/business/britain-s-ft-plans-india-edition-soon-ceo/story-aCeX5bg9qxqMnPgy6pZHBN.html) So if elite Indians want to see the world through a Western prism, how come the FT and others have done so badly in the Indian market? Thanks again