Dear Global Jigsaw,

For the last year and a half, I have hosted an occasional “salon” at my home in Madrid, called The Story of Things. Inspired by how cosmopolitan a circle of people are suddenly swirling about Spain’s capital city (more on how and why here), the idea was to create a space for people to bring in objects that told interesting stories from around the world.

I have now hosted five editions of The Stories and we’ve heard tales of jewellery presented by Haile Selassie, sculptures made of IV drip tubing in a Ukrainian hospital, and pens fashioned out of bullets to sign a peace accord in Colombia. However, it soon became clear that the objects were secondary to the stories themselves. And increasingly the stories focused on family – a grandfather’s dilemma during the Spanish Civil War, an aristocratic, whisky-distilling Scottish ancestor, a journalist father covering the Gulf War in Kuwait.

A selection of photographs taken at The Story of Things

Today’s newsletter features a guest post by Fiona Govan, a British journalist and long-term resident in Spain, who at the last edition of The Stories presented a stranger-than-fiction tale about her grandmother’s secret past. The story, which she is now in the process of writing a book about, involves the kind of border-crossing melange of geography and identity that I increasingly believe to be more the norm than the exception. The Global Jigsaw would have been an apt moniker for Fiona’s Babula’s journey across continents and cultures.

I hope you enjoy it.

I am convinced that there is not one amongst us whose grandparents’ stories wouldn’t contain the kernel of a novel. Here’s a link to my own paternal grandmother’s wildly cinematic life journey:

Orphaned and almost married at 10

Hola Global Jigsaw, With it having been International Women’s Day last week, I’ve been thinking more than ever about how to explain “Indian women” to the rest of the world. It’s common for an Indian abroad to be interrogated about the status of women back home – and small wonder given the outrageously misogynistic rapes/dowry deaths/acid attacks that are…

****

The breadcrumb trail of a family secret

It was a throwaway comment from a fellow guest at a friend’s wedding in Mallorca that started it. “How lovely to meet another Ukrainian Jewish emigre, there’s not many that escaped the war…”

Elegant Liliana from Uruguay had sat next to my Iranian mother during the wedding meal, and the women, both in their late sixties, had bonded over recollections of dishes cooked by their mothers during their infancy: cotlets, smoked herring and dumplings were among their reminiscences. Beneath fairy lights twinkling as the sun set, they’d laughed about the cure-all sweetened egg drink they both called gogelmogel and compared family recipes for borscht and chicken soup

Food, insisted my mother, was the main topic of conversation, spoken in a rusty sort of Russian once they’d worked out the only language they had in common. My mother had admitted she knew little of her own mother’s heritage beyond the fact that she’d been born in Kiev in the early 1920s, while her new friend described how her own parents had fled from Odessa shortly after the Nazis started their march into the USSR, finally settling in South America.

“We didn’t even mention being Jewish,” my mother insisted to me later. “How strange for her to think that when we only really talked about food.”

But was it strange? Could a shared food culture indicate a shared Jewish heritage? To me it seemed likely, the period they were talking about was long before experimenting with recipes from other cultures became fashionable.

My mother wasn’t convinced or even particularly interested in the matter. For her, such questions were not answerable. She has always been a blank page when it comes to my grandmother’s origins.

For my mother, the story began with her own memories; of growing up in Teheran surrounded by cousins and then moving to London as a teenager in the early 1960s with her Iranian father, Houshang and younger sister, Firouzeh.

When my parents got married and bought a house on the outskirts of London in leafy Buckinghamshire, Babula - as my brother and I called our grandmother - bought a place next door-but-one and was very much a part of our daily lives.

But when I was 11, just at the age when I might have become curious and asked my grandmother about her early life, she died suddenly after a fall while on holiday in the south of France.

Some 30 years later, sparked by that conversation on a Mallorcan hillside overlooking the sea, I knew it was time to find out more. And there began the quest to unravel the secrets and solve the mystery of my grandmother’s identity and thereby, I hoped, my own.

Not long after, I decided to get scientific about it and bought DNA testing kits for both me and my mother. Enough weeks went past after sending off our saliva sample that it came as a surprise when I received an email telling me our results were in. One thing was clear - the results revealed that I was indeed 25 percent Ashekenazi Jewish and any doubt that it might have been a legacy of my paternal family, was removed when my mother’s confirmed she had a 50 percent genetic make-up of Ashekenazi with a map pinpointing the zone covering Eastern Europe specifically in the Polish/Ukrainian region.

So Liliana, my mother’s random wedding breakfast companion, had been right and had known more about us than we did ourselves. But how had my grandmother, a young Jewish woman from Kiev, found her way across the USSR to Iran of all places at the height of the World War Two? I was determined to find out and grilled my mother for every recollection she had that might provide a clue. What had Babula told her about her own family? Did she know her maiden name? How had she got to Tehran?

Gradually a narrative of sorts began emerging. There were more gaps than facts but the clues were there. And then, from within a old trunk at the back of my mother’s wardrobe, I found a faded brown leather booklet, thinner than a passport and the markings on the front, if there had ever been any, had long since been rubbed off.

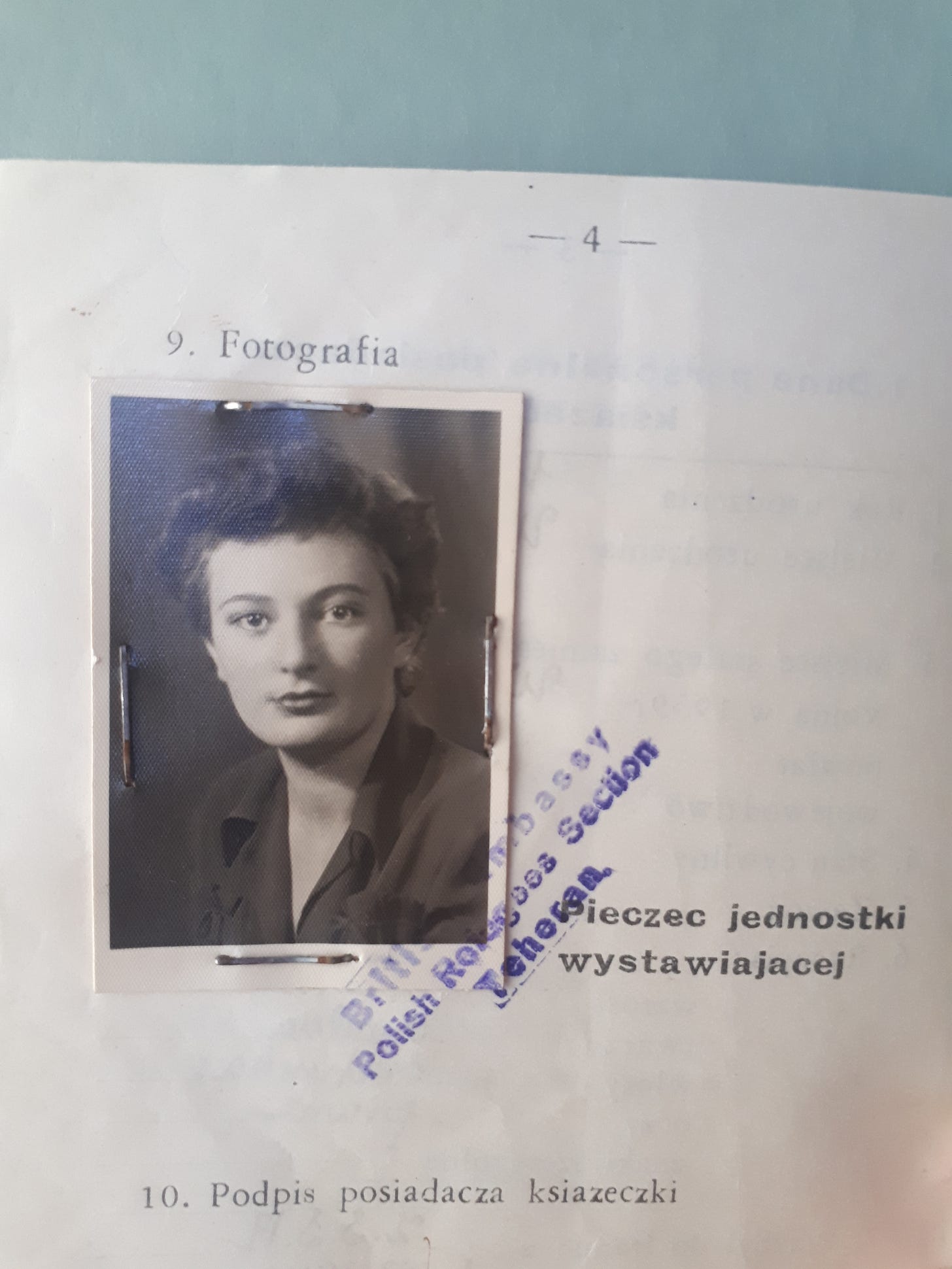

It was a ration book issued by the British Embassy Polish Refugees Section, Teheran that contained at least some of the information I had been yearning for.

The black and white photo inside was barely recognisible as the grandmother I knew: wide eyes staring dreamily out of a youthful clear complexion, hair swept up from her face and her full lips almost pursed without the trace of a smile.

Thanks to this thin inconspicuous booklet issued in 1943 I learnt that Maria Jankowska had arrived in Iran by boat from the USSR on September 1st 1942.

Aged just 19 and all alone, Maria had been among the 116,000 refugees who poured into the sleepy Persian port town of Bandar Pahlavi that spring and summer, converting it into a tent city. Rife with cholera and dysentery, the vast camp on the shores of the Caspian was a place of refuge for those who had been deported from their homeland, survived years in work camps and remote settlements across Soviet Asia and had survived to see an ‘amnesty’ declared by Stalin. While thousands had perished of hunger, cold and disease in the camps or been shot in mass executions, those who made the journey across the Caspian had been allowed to under a deal to create Anders’ Army, a Polish army in exile under the command of General Wldyslaw Anders, himself a survivor of the Katyn Forest Massacre.

Alongside the roughly 75,000 soldiers who had enlisted across the USSR and who made it to safety in Iran were their families; mothers and babes in arms, elderly men and women and an estimated 1,000 Polish children who had been orphaned during the arduous exodus.

There were also Jewish stowaways - those who had obtained false papers or who claimed to be married to Polish officers.

We can’t know what my grandmother lived through that saw her leave her birthplace in Kyiv and travel some 3,400km to Krasnovodsk, the port in Soviet Turkmenistan that served as a muster point for army recruits and their relatives.

I’ll never know if she convinced officials to let her board the boat there or stowed away spending the 250 nautical mile crossing hidden on the creaky old coal transportation ship.

But I know that she emerged as a survivor in Iran to begin a new life with a new name and a new identity, leaving only the faintest trail of challah breadcrumbs to hint at the secrets of the past.

I am only now piecing together her journey from Kiev to the disease-ridden refugee camp and onto the cafe culture of post-war Teheran. I am working on a book to tell the story of how she came to be the eighth wife of a Sheikh- the heir to a lost kingdom in southern Iran - and then reappeared in Teheran with my mother in tow, to reinvent herself once more.

****

Today’s guest writer, Fiona Govan, with her mother, Larissa.

Fiona Govan is a British freelance journalist based in Madrid. She has been a foreign correspondent reporting from across Europe and beyond, as well as an editor and travel writer.

****

Thank you for reading. Do share the stories of your own grandparents. Have you discovered any surprising family secrets? And as always, I leave you with a request to upgrade to a paid subscription to the Global Jigsaw, if at all possible for you.

Until soon,

Pallavi

Sorry dear Pallavi,

I failed to respond to your last blog's suggestion on An Idea of India. It is more than well dated.

Here the next upcoming book on the topic: “Discovering India Anew: Out of Africa to Its Early History” by Alan Machado (Prabhu).

Aldo

This is wonderful. Thank you for sharing! Truly love the global puzzle of the story, of life!