The wound is the place where the light enters you

On breaking and healing - (and on soliciting (cough) paid subscriptions)

This is a big day for me and a momentous post for two reasons:

First, I’m switching on the option for readers to pay for this newsletter. Eeeks! I feel both embarrassed and nervous to ask anyone to pay to read my sribblings…but if what I send you every week, has resonance or value for you, do consider switching to a paid subscription.

For only the price of a (fancy) cup of coffee a month ($5), you can become Pallavi’s Patron - and I promise to buy you a (fancy) coffee should we ever meet - so you’ll get back the value of at least one month’s subscription, some post-pandemic day :-)

Subscribers will also get personalized travel recommendations from me, for both the world’s trendiest cities and its less-known “secret” locations.

You could also consider becoming a Founder Patron- and for a 100 bucks gain my eternal thanks and that of the World of Letters!

Paying is OPTIONAL. The Global Jigsaw remains free for those who would rather not pay for its content.

Second, this week’s post is the most personal I have written for public consumption. That sounds like quite a claim given that my writing is usually personal in nature. But much of that writing has in fact been the equivalent of “Facebook” memoir: a partial, smiling snapshot. This piece is the non-Facebook version: about breaking, and about scars as upgrades.

I chose to write it now, well, because of the enormous collective grief weighing down India. The last year and a half has seen the globe stalked by death and disease, and starved of touch. We’ve hidden ourselves away at home; behind masks; behind technology. We have been, if not broken, dented.

But while we may yet need to hide our bodies away from COVID, our emotions don’t need masks. So here goes.

************

The falseness of guru-ness

Looking back at my posts here at The Global Jigsaw, I realize I’ve been a bit disingenuous. There are times I’ve almost come across as Guru-like. I’ve talked a lot about finding joy and learning to appreciate the wonders of, well, everywhere.

But the fact is that the reason I focus on joy and appreciation as much as I do, is that I know how easy it is to lose that capacity. It’s devastatingly fragile. We are attached to our mental health by a gossamer-thin thread that can snap silently and suddenly.

Three months of madness

I woke up one morning in early January 2015 with my heart in my mouth. It felt like I was teetering on a precipice, about to fall and fall and fall. I was in full blown fight or flight mode: the rush of adrenaline, the racing heart, plunging stomach, a physical need to run away to be safe. Except there was nothing to fight or flee from.

My kids (7 and 4 at the time) munched on their breakfast without incident, got dressed and went to school. My husband kissed me goodbye and took off for office. And I? I sat at my desk in the dappled sunlight as it filtered into my study, bewildered, battered. I felt like I was being pounded from within. My heartbeat was a roar in my ears.

I lived with that soundtrack for the next three months, as I ate meals, worked on articles, watched movies, read bedtime stories to my boys, and lay sleepless in bed at night.

Cracked

To date, I don’t really know what ‘happened’ to me during those months. I’ve spoken to different doctors over the years. One believes I had a depressive episode. Another thinks I have “generalized anxiety.” There would have been a time when I’d have deemed to have had a nervous breakdown. A malfunction of the nervous system; a crack in the mind; a wound in the breath.

Up until that morning in January, I was a chipper sort. I rarely experienced deep sadness. I seemed to have the ability to just take the cards I’d been dealt and keep playing the game.

My first child, Ishaan was super colicky. He cried and fought sleep for several months after he was born in 2008. Even after he began to sleep better, I stopped sleeping. For years I never had a restful night. It’s a rare condition apparently, called chronic postpartum insomnia.

Warning signs

In early 2014, I developed migraines for the first time. These are frighteningly intense headaches that can last days and are so bad you often end up throwing up. I thought I had a brain tumour. But no, I was in the pink of health, or so all the scans insisted.

I began to drop weight. At one point I weighed 44 kg. People kept telling me I looked great.

I had a battery of tests. Bloods, endoscopy, everything my beleaguered doctor could think of. I went for a second opinion and was told to eat more ice cream to gain weight. Back to the original doctor. He asked me, “Are you depressed?”

“No!” I smiled. And I wasn’t.

Being “fine”

Through all those months of headaches and losing weight, I’d been ‘fine.’ I’d had a new book out. I’d travelled for work. Made new friends. I’d hired a personal trainer to step up my exercise regime. Been appointed a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum. I’d adjudicated the endless fights my children had. Brushed my cats so their hair wouldn’t get tangled. I’d potty trained my younger son, who resisted being parted from his diapers with the iron will of a toddler.

And then I’d collapsed. Although the collapse was internal. On the outside I was thin.

I continued to work. I continued to parent. I tried to meditate. I panicked. I fought the panic. I counted my numerous blessings: my sprawling home, my interesting work, my family, the fact that I lived in marvelous Indonesia. I cried in the bathroom. I cried in bed. I cried through my attempts at meditation. And on and on my heart would pound and my muscles clench and my brain feel like it was running a marathon, even as I told it to rest, to rest.

A Shrewdness of shrinks

I met my first psychiatrist in March 2015. He’d looked on phlegmatically while I’d described my descent into madness. He’d handed me a tissue and written out a prescription for an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) - a standard anti-depressant. Within 2 weeks, I was better. Two weeks more and I was “normal.”

Over the years, I have tried stopping my meds on three different occasions. Each time I was fine for about 10 days before a return of the racing heart. About a year ago, I stopped trying to stop. And I feel so well, I’ve almost forgotten that I’m not.

I take a very low dose of the anti-depressant. There, I couldn’t stop myself from saying it, even though I’d sworn at the outset of writing this piece that I wouldn’t refer to dosage. Because it doesn’t matter if you take a low dose or a high dose. Meds are great. They are a badge of strength. They are a way of being healthy.

I know this. I state it without reservation. And yet I feel ashamed that I need to take pills to be hale. That without them I am in effect “mad,” if by mad we mean mentally unwell.

In Japan, my psychiatrist was an elderly lady. She spoke halting English, but always during our sessions together she would reference the seasons. “Be careful in the summer,” she would say. “The heat affects our mood.” She said the same pretty much of every season. I miss her.

The next psychiatrist I saw, asked me to talk about my family history of mental health. I began talking and forty-five minutes later when I had detailed parents and first cousins, and was about to move onto sundry uncles twice removed, he gently cleared his throat. “There is a difference,” he said, “between idiosyncrasies and clinical conditions.”

And there is. I know this, because I’m not particularly idiosyncratic – if you don’t count the fact that I hate the smell of oranges and the sight of people brushing their teeth-but I do have a clinical condition; low on the spectrum of madness, but high enough to know how lucky we are to have the capacity to marvel – at the scent of lavender or sunlight in a soap bubble.

Kintsugi

And so, because this is The Global Jigsaw after all, we come to kintsugi.

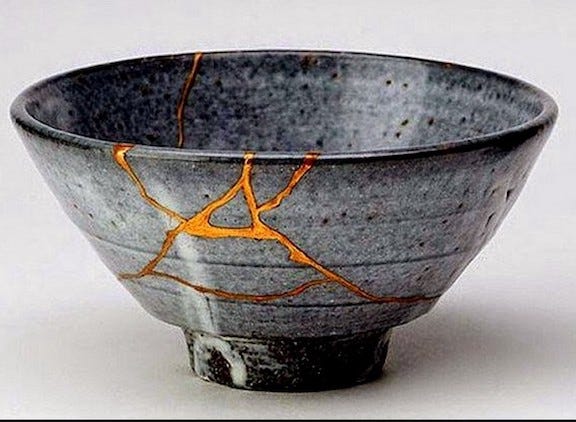

I’d first heard of kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing ceramics, even before moving to Tokyo. A meme had been doing the rounds on Facebook with the picture of a grey bowl rent by snaking golden tributaries, and the words: Japanese repair broken pottery with powder gold lacquer to highlight imperfections, not hide them.

Unlike other methods of repair like welding or gluing, kintsugi's power lay in its refusal to disguise the brokenness of an object. It did not aim to make what was broken as good as new, but by making the cracks luminescent, it transformed the object into something different, and arguably even more valuable.

Kintsugi inscribed an object's story into its body: the moment of the breakage, the fact that it was loved enough to be repaired; that it was likely to be handled with care in the future. All of this was written into the veins of gold and lacquer that marked once broken artifacts.

We have all been broken at some point. And the essence of who we are is not located in some flawless image we might present, but along the fault-lines of our biographies. Kintsugi encourages us to embrace our past along with its scars; to realize that our cracks make us even more beautiful

So it is with me.

This last year has left many of bereft. Here’s to filling the scars with gold.

Until next week xoxo

Great blog, keep writing. Love the concept of Kintsugi. Do explore Ayurveda, you will find subtle answers, especially living in synch with constitution (Vitta-Pitta-Kapha). Highly recommend the book “Prakriti - Your Ayurvedic Constitution by Robert Svobodha”.

Have you ever considered a simple biological explanation - like a messed-up biome? We are first and foremost animals. Our biome has more cells than our body. The vagus neural system is the size of the spinal cord - 80% of the signals go from our bowels UP to the brain. It may just be that "something" disturbed one's biome, with catastrophic effects.

Toxoplasmosis being the poster case: the parasite turns adventurous the mind of the mouse. The mouse is easily eaten by the cat as the result - where the parasite reproduces.

We always chose the complicated psychological hypothesis - rather than simply experimenting with a different diet by trial and error.

This being said, the pain is real, and no less so because it may be trivial rather than complex.

Great that you have come out of it with clear-cut golden scars. "Crooked Timber" does not accept gold easily.

I'll subscribe when I'm back in my country. Do not trust CC algorithms abroad.