Indonesia cozies up to both the US and China

"“One thousand friends are too few, one enemy is too many.”

Hola Global Jigsaw,

Hope everyone is doing well. Madrid is suddenly very cold, leaving me a tad nostalgic for our tropical years in Indonesia. Which brings us to this post, about the archipelago’s newly instated President, and why the world should pay attention to him.

Before you read on, could I ask you to become a paid subscriber of this newsletter? Given the state of the mainstream media (financial and ideological disarray) and my itinerant life circumstances, it is through the entrepreneurial endeavor that is the Global Jigsaw, that I attempt to make a living. So,

Terima Kasih!

xxxxx

Three weeks after his inauguration as Indonesia’s new President, Prabowo Subianto, has taken to the air. He is currently on an around-the-world tour that includes China, the United States, Peru, Brazil, the United Kingdom and “several,” unspecified Middle Eastern countries. Just three weeks into the job, Prabowo is already being billed as Indonesia’s “foreign policy President.” A moniker that springs from his obvious enjoyment of developing personal relationships with world leaders, and his stated desire to have his, often overlooked, nation take its place among the geostrategic movers and shakers of the new world order in the making.

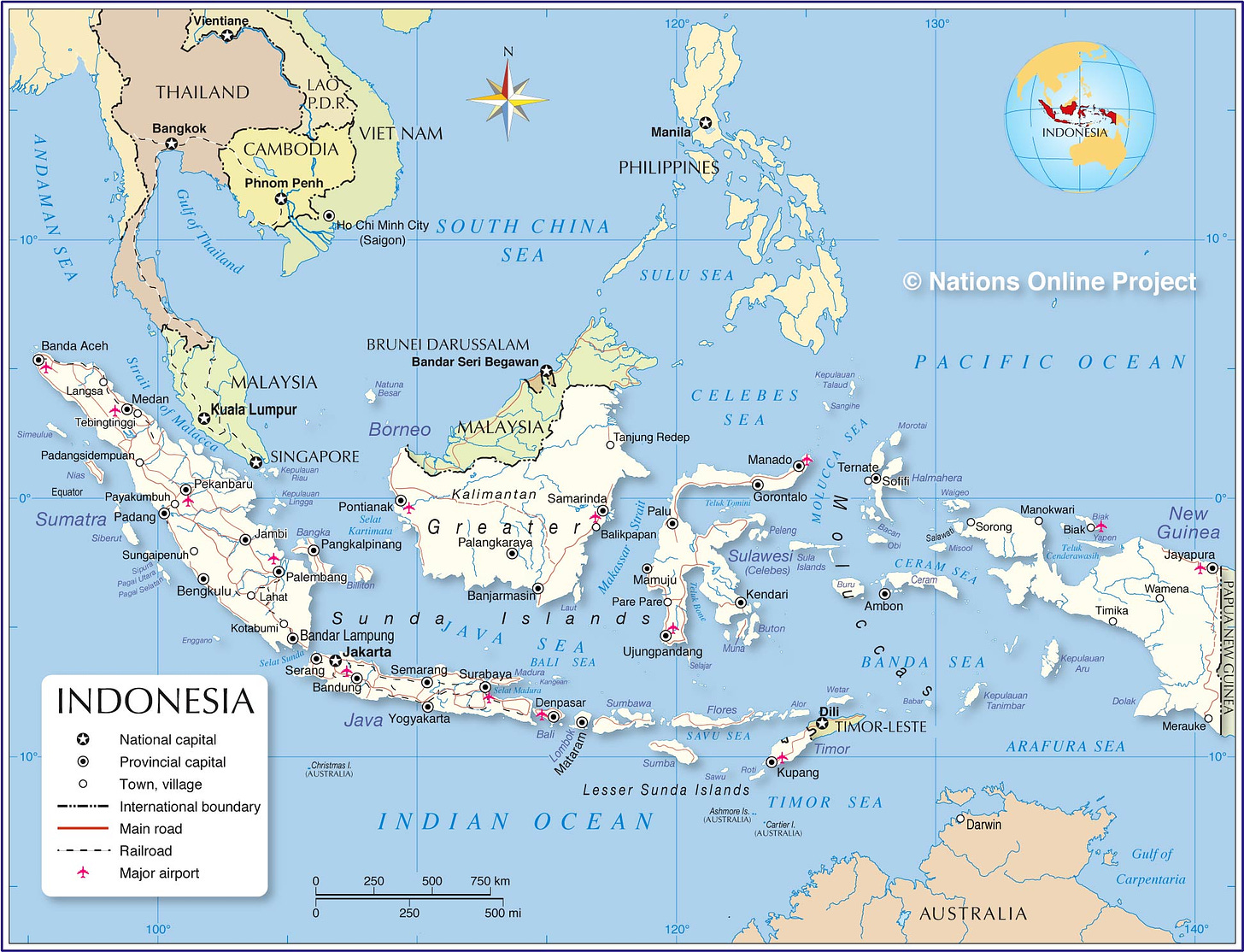

The Indonesian archipelago’s propensity to sidle along under the geopolitical radar, was not helped by its previous leader, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who shied away from the international stage, and was more comfortable focusing on domestic issues like infrastructure. This made it easy for the world to forget just how strategically significant Indonesia is.

It is not only the world’s fourth-most populous country, but also its largest Muslim-majority democracy. Its size makes it a natural leader amongst the 10 ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) nations, a region roiled by ongoing maritime boundary disputes with China. Nonetheless, Jakarta has close economic ties with Beijing. Moreover, as a Muslim nation, it speaks a language that resonates in the Middle East. And it is on good terms with Russia, while enjoying strong military ties with the United States. Prabowo often says, “One thousand friends are too few, one enemy is too many.”

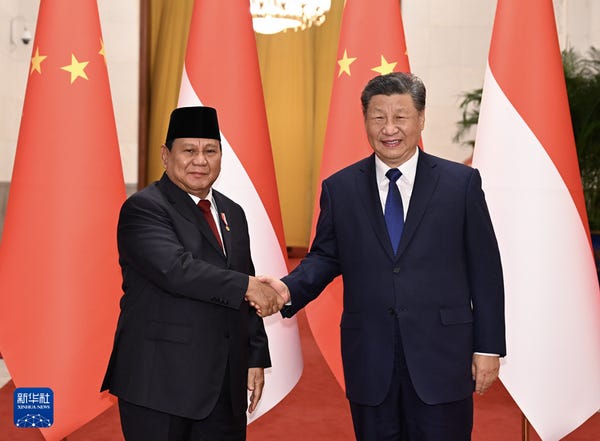

The new President certainly walks the talk. In April this year, in his dual capacity as Indonesia’s Defence Minister and President-elect, he visited China, Japan and Malaysia, sweet-talking the leaders of all three nations. A month later, he was in the Middle East where he proposed sending Indonesian peacekeeping forces to help resolve the conflict in Gaza. Around the same time, he met with Ukrainian President, Zelensky, at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. And July saw the indefatigable traveler at the Kremlin, chatting with President Putin, and calling Russia “a great friend.”

The billion-rupiah question is whether it is really possible to achieve this level of friendly fluidity in a world that is siloed in hostile camps? This is a question that has equal pertinence for the archipelago’s maritime neighbour, India. The two nations share more than similar sounding names. Both are faced with the challenge of updating their traditional, non-aligned Cold War stance, to the 21st century equivalent of multi-aligned, strategic autonomy.

India and Indonesia are both cognizant of the opportunity that the United States’ need for regional counterweights to China’s growing clout presents. But Indonesia is in an even better position, given that, unlike India, it lacks an overt territorial dispute with China. Moreover, unlike New Delhi, which is seen by Beijing as a potential rival, Jakarta’s modest international standing plays to its advantage in that it is not seen as an adversary by China.

China is Indonesia’s largest economic partner and investor with bilateral trade at USD 139.42 billion, in 2023. Prabowo, like Jokowi before him, is also committed to promoting Indonesia’s domestic electric vehicle supply chain and exploiting its critical mineral resources (the nation is the world’s largest nickel producer). China has poured investments into both areas, as well as into developing much needed infrastructure. Last year, Indonesia was the largest recipient of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) funding, receiving USD 7.3 billion of Chinese money.

Under Prabowo’s newborn leadership, Jakarta has already announced that it will join the BRICS grouping of major emerging economies that includes China and Russia (as well as India, Brazil and South Africa), in addition to launching its first joint drills with the Russian military. These exercises began this Monday and will last until Friday. Russia has sent three corvette-class warships, a medium tanker, a military helicopter and a tugboat, according to the Indonesian navy.

It speaks to Prabowo’s chutzpah that the exercises are taking place, even as he is in the United States, shaking hands with Joe Biden. Military cooperation with Washington DC is a cornerstone of Indonesian foreign policy. Since 2007, Indonesia and the U.S. have conducted two-week joint military training and drills annually, an exercise that has now expanded to include 22 other nations. Last year the Indonesian Defence Department’s procured 24 F-15 fighter jets and 24 S-70Ms Black Hawk transport helicopters from the United States.

Prabowo’s agility, given the strategic acrobatics it will require to keep both Beijing and Washington DC by Jakarta’s side, will certainly be tested in the coming months. This is especially so in the context of a ramped-up trade war between the US and China that is likely under the upcoming Trump presidency.

But Indonesia’s friendship is a valuable prize, given its status as a major littoral player, at a key maritime choke point, in a region populated by allies of the US that are wary of China. And Prabowo knows this.

Something Beijing has been keeping a wary eye on, is the new President’s stance on the South China Sea conflict. Prabowo has long postured as a tough nationalist, an attitude that could make him more likely to take an anti-China stance were Indonesia to be dragged into the fracas. In the past, Prabowo has expressed an intent to begin the exploitation of gas reserves in the North Natuna Sea, an Indonesian region that falls within China’s maritime claims.

Following his meeting with Xi Jinping last weekend however, the joint statement mentioned that the two countries had “reached important common understanding on joint development in areas of overlapping claims” (italics mine). Some analysts are interpreting this as a departure from Indonesia’s long-held stance that the archipelago is a non-claimant state in the South China Sea and therefore has no overlapping jurisdiction with China. There is some concern that the wording of the agreement could be interpreted as a change in Jakarta’s position, to its disadvantage. Indonesia’s ministry of foreign affairs however, said that the agreement will have no impact on the nation’s sovereign rights.

What is unambiguous is that it will not be easy for Prabowo to position Indonesia as a powerful global mediator, with a bone in no fight. However, given its demographic, economic, religious and geographical profile, he might just pull it off. Watch this space.

xxx

Please share and comment. Your feedback is deeply appreciated. Until next week,

Pallavi